GDC 2013: Designing Journey

Jenova Chen’s talk at the 2013 Game Developer’s Conference opened to thunderous, prolonged applause. The night before, his game Journey swept the Game Developers Choice Awards with six wins, including Game of the Year. These join a long and impressive list of accolades that includes five BAFTAs, eight D.I.C.E. awards, three VGAs, and numerous others (including our Aggie Award for Best Console Adventure).

An hour later, near the end of his talk about Journey’s grueling three-year development, Chen admitted, “Before the award season I still questioned whether it was worth it.”

|

The team that made Journey.

|

Journey is the third game from Chen’s studio thatgamecompany, whose other releases include flOw and flower (all PlayStation 3 exclusives funded by Sony). Chen started his talk by explaining that he sees the entertainment industry as a means to fulfill human desires—you eat food when you’re hungry and drink water when you’re thirsty, and when you’re craving a specific emotion, that’s when you turn to entertainment. But most games focus on the same few emotions. “When we started thatgamecompany, we wanted to push the boundaries of what kind of emotion games can communicate to players. We thought if there’s a variety of feelings available in gaming, it will make gaming a more healthy medium, and it will help people feel something new,” Chen said.

He first had the idea for Journey in 2006, when he’d been playing World of WarCraft for about three years (initially as an alpha tester) and was starting to get sick of it. Busy with school, he had almost no social life, so being online with real people playing WoW made him feel less lonely. But he wanted to have an emotional exchange with other players, and most other players were more interested in talking about strategy or loot than forging a friendship. Chen imagined a game with no enemies to kill, where people could forget competition and focus on the fact that we’re all human. He believed that not even gender or age should get in the way of building a personal bond: “When I feel a connection to someone in WoW and then learn it’s a 12 year old boy, it’s such a disappointment.”

With WoW as his reference point, he envisioned an MMO where everyone would be on a path searching for something. He imagined a scenario where one person was standing on a bridge looking at a waterfall and another would stop to think about why the other player was looking there, with the act of pausing next to someone making that moment meaningful for both of them. Another early vision was of a group of people approaching a dust cloud with monsters lurking beyond; players would need to hold hands to make their way through the dust, with each person in the chain protecting the one behind them.

The opportunity to make Journey didn’t arise until 2009, after thatgamecompany had finished flower and felt ready to tackle online gameplay. Chen was excited to figure out how to induce a new emotion between two strangers online, but he wasn’t entirely sure what that emotion should be. He looked at popular co-op games, which mainly involved team fights or team survival, but kept hearing from players of those games how much they hated other online players. He wanted Journey to make players trust each other, not hate each other.

|

|

As seen in these early concepts, Chen originally envisioned a game where a team of players would help each other along a quest.

He started to formulate Journey’s story of lone travelers crossing a desert to reach a distant mountain after speaking to astronauts about the experience of going into space. “Apparently the ones who go to the moon come back and become very religious. There’s something very spiritual about it,” Chen explained. “I met the guy who drove the first moon buggy and he said, ‘On the moon there’s nothing. There’s no sound because there’s no air, it’s quiet. The earth is so small it’s like your thumbnail, you can cover it up … and you can’t help but think, why? Why are we here, what’s the purpose of the universe?’ They’re faced with a lot of unknowns.”

|

|

Chen knew from studying psychology that a sense of awe is often directly tied to religion. This revelation inspired him to think about how we live our lives today. He concluded that although we’re highly empowered by technology—we can move fast in cars and airplanes, can live above the clouds in skyscrapers, and can use cell phones to talk to anybody at any time—we’re also trapped by this empowerment. (Checking your email while on the toilet, for example.) In games, such empowerment is often represented by a character who carries a gun or a sword, and when a game provides you with a weapon, using that weapon becomes the biggest priority. And in online games, players usually think more about getting items and becoming more powerful than they do about helping others. So when Chen thought about designing a social experience that would connect people, he decided he’d need to reverse the power relationship between the player and the world. Journey’s world could not be noisy. There could be no guns. And there shouldn’t be too many people, because when there are only two people around, the guy in the distance becomes a lot more interesting.

Using music by composer Austin Wintory to set the mood, thatgamecompany began the design process. (Wintory was ultimately nominated for a Grammy for Journey’s music.) During a four-month prototype stage, they tested many gameplay styles that worked okay in 2D mock-ups, but didn’t translate well to 3D. Some gameplay ideas had to be abandoned, such as two players combining their strength to push a rock out of the path or using individual special abilities in tandem, because Sony requested inclusion of a single-player mode. As their ideas for how players would explore the world solidified, they focused on “graphics as gameplay,” conceptualizing visuals to make the journey itself more fun. (Examples include the sand trail that appears behind you as you walk, dunes and landmarks that provide a sense of movement, and the ability to surf in the sand.)

|

Inspiration for Journey’s sand path and dunes. |

They wanted to make the multiplayer simple enough that even non-gamers could figure it out, and to avoid real-world distractions such as usernames and voice chat that would take players out of the game world. So they created a system where anonymous players would be paired automatically, with usernames only shown at the end of the journey. Thinking real-world friends would be annoyed by the inability to chat with each other, they decided not to support friend invites and instead created a “seamless lobby system” that kept co-op pairing entirely behind the scenes. To avoid groups developing an “us versus them” mentality that could leave some players feeling left out, they limited co-op to two players to focus on one-on-one collaboration. And to provide a balance between ability and challenge, they left it up to players whether they wanted to stay with a partner or walk away and find someone else better suited to their playing style. “When you have the choice to leave, the co-op is more real and sincere, and it’s possible to have a stronger collaboration,” Chen explained.

Through playtesting, they identified co-op mechanics that didn’t work as they’d intended. For example, in Journey you frequently encounter cloth strands that allow you to fly. When playing with a companion, if both players love to fly and one player always got to the strands first, the other would start to get annoyed. “We thought the player could drop the resource after using it, instead of consuming it. In an early stage 3D prototype, if the player flies, he drops a bunch of strands for the other to pick up for free—it’s kind of a communism thing,” Chen said. Psychologically, this felt less like sharing and more like the second player was stealing from the first, which bred resentment. So they eliminated any sense of possession by providing infinite resources but giving players a limited pocket size. This way people could always pick up what they needed, everyone could fly, and players didn’t end up hating each other.

|

An example of co-op gameplay that could turn ugly. |

Collision was another co-op issue they needed to work out. In most online games there is no collision—people just walk through each other. But thatgamecompany liked the idea of two people helping each other over a rock, for example. “We thought it would deepen the emotion of trusting each other, so we added physics so you feel the resistance of helping each other,” Chen explained. But instead of helping each other, players started pushing each other around—including lead engineer John Edwards, when he and Chen were playtesting the game together. “I was like, ‘You know this game is about helping each other and connection’ and he’d just stare at me laughing across the office. For quite a while I was disappointed by humanity,” Chen said. “Then one day I met a spiritual psychologist, so I talked to her about this dilemma about humanity, and she said ‘It’s because your players are babies. When [people] transport [themselves] from the real world to the virtual space, they don’t carry the morality of our real life. They seek feedback.’” Helping someone over a rock provides almost no feedback, but killing someone comes with animation, the sound of crying, the player waiting for you to revive them—all forms of feedback. So they got rid of collision, and instead when you’re next to each other each character’s power source is recharged. As a result, the game provides a lot of feedback when you’re near each other, but no feedback for harming each other.

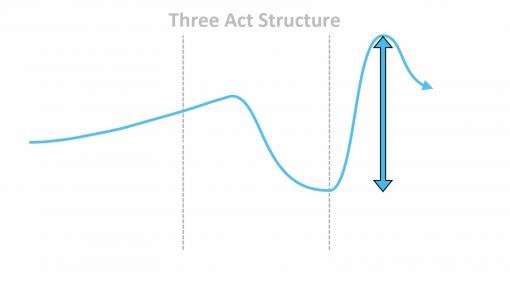

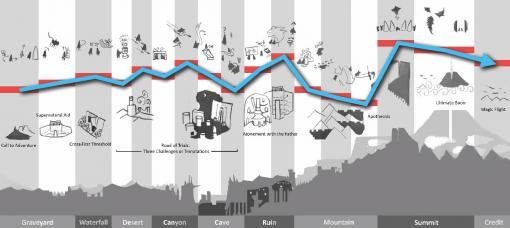

The last major task in the early design process was to make sure the game’s three act narrative provided a sufficient emotional catharsis. They looked at Joseph Campbell’s theory of the Hero’s Journey, a structure of storytelling that portrays a human being’s transformation. “When I lined up the transformation of the Hero’s Journey with the intensity of the three act structure, and the transformation of a character’s life from birth to death, it’s almost perfectly aligned—a hero’s journey that’s also a human’s life,” Chen said. Based on this, they created the narrative arc of Journey, and based on the narrative arc, they created the landscape of the world. They figured out how the character would grow from young to old and eventually transcendence during this journey, and used the story to inform the mood, colors, and details of each area in the world. Finally, they came up with an even more detailed emotional arc involving specific gameplay elements, which they divided up into larger and smaller levels.

In the three-act structure of storytelling, the narrative hits its lowest point at the end of the second act, then quickly rises to its highest point, providing an emotional catharsis.

The developers linked the stages of the character’s life to the stages of the journey, reflecting the three-act structure in the landscape.

They mapped out gameplay events that would simultaneously carry the player through the three-act structure and the stages of the Hero’s Journey.

(Warning: The following paragraph includes information that may be considered a spoiler.)

Though it all seemed to work on paper, after two years of development they were discouraged that playtesters still weren’t experiencing the journey as they’d intended. When he received feedback that the game should end after the player dies on the mountain (the end of act two) because everything that came afterward “was making the game worse,” Chen realized the problem: the emotional high that came after the mountain level wasn’t enough of a rise from the lowest low to provide a satisfying catharsis. To improve this, he determined that the mountain level needed to bring players even lower. Currently, it felt tedious: lots of wind blew at you and climbing the mountain took forever. The team decided to make this more of an active struggle, creating hundreds of new animations to make the character appear weak against the wind, climb slowly, and shout weakly. Originally, you could not be attacked on the mountain, but they changed this so the mountain was no longer safe. And to draw out the struggle, they made the level longer, adding two new areas before the final “walk of death” and continuously slowing down the player’s input and dimming the light (a symbol of hope).

|

|

With the addition of new animations, the struggle to climb the mountain took on more impact. Meanwhile, a new sense of freedom on the summit boosted the emotional high.

Next, they increased the final level’s emotional high by making the summit a lot more exciting and free. Initially, travel through the area was on rails, which hampered the sense of freedom and made the sequence less cinematic. They opened up the entire level to exploration and added a surfing area to bring back the excitement players experienced in earlier levels. In the final game, right up until you walk into the light you’re free to go anywhere, and even walking into the light and triggering the end of the game is the player’s decision. “If you think about other highs in the journey, whether it’s the surfing part or the water temple or the summit, it’s always about the movement and the freedom,” Chen said. After working an extra year to implement all of these changes, they held another playtest. Of 25 players, Chen says three had tears in their eyes when the journey ended: “That’s how we knew the emotion was working.”

The game finally launched in March 2012, after the schedule was extended twice and the budget depleted. (Though not mentioned in this presentation, Chen has stated elsewhere that Journey nearly bankrupted thatgamecompany; in another GDC talk, studio cofounder Kellee Santiago mentioned that due to their agreement with Sony, they’ll see little money from the game.) One of the first signs that their experiment had paid off came from a forum thread where players apologized to each other for having to leave partway through a playthrough. “I can never imagine a Call of Duty player doing that, but they’re the same people,” Chen said. “People who play the game remember the awe, the sublime beauty of the world, they remember being scared and afraid of the danger, and they remember working together and helping each other to make it to the end.”

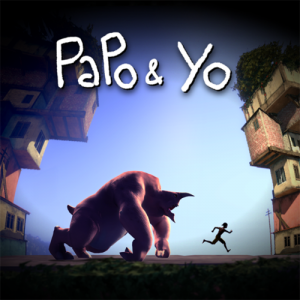

Fan art of two journeyers huddling in the snow.

In closing, Chen read an email from someone who played Journey with her father after his diagnosis of terminal cancer. (This letter was just one of nearly 900 that the team has received from fans so far.) “In my dad’s and in my own experience with Journey, it was about him, and his journey to the ultimate end, and I believe we encountered your game at the most perfect time,” the email said. “I am Sophia, I am 15, and your game changed my life for the better.”

Receiving this email reminded Chen of a piece of fan art (shown above) that depicts two companions huddled together in the snow. “We’re only here for a certain amount of time,” he said, “so let’s help each other and make each other’s lives better. As a developer, that’s the best thing we can do, and that’s why I love making games.”

He received a standing ovation.