An overview of genre history, by The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games: Part I

The adventure genre has a rich history dating back to the earliest days of PC gaming, and an equally impressive legacy begun in the earliest days of computer graphics. No single book could hope to capture it all in print, but The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games comes awfully close. Published by Bitmap Books, this incredible 500-page coffee table hardcover is a treasure trove of visual riches from both popular classics and lesser-known indie efforts alike.

But don’t let its title fool you: there is much more than just art in this book, with more than 50 interviews with key developers, designers and artists that helped shape the genre over the years. Indeed, the upcoming second edition of The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games will contain even more, including such Sierra luminaries as Ken Williams and Lori and Corey Cole.

To help celebrate the reprint (due out August 10th), Adventure Gamers is partnering with Bitmap Books to offer a glimpse inside the covers of this incredible collection with a four-part article series over the next month that includes both text excerpts and artwork. First up? Where better to begin than an examination of the genre’s illustrious history itself. Or the first half of it, anyway.

(Note: Click on any image to enlarge.)

The history of point-and-click adventure games

From its humble 2D origins to recent hyper-realistic outings, the graphic adventure has been entertaining players for decades, with companies like LucasArts, Sierra, Revolution, Westwood Studios and Adventure Soft all contributing seminal classics to the point-and-click library. Join us as we take a look back at the birth, evolution and resurrection of a truly classic genre.

Despite the relentless march of technology it’s quite rare for a video game genre to boom to the point that it becomes dominant for several years and then bust so dramatically that it falls almost entirely out of favour. Shooters have evolved over time from crude, single-screen 2D affairs to intense and immersive first-person blasters, while the humble platformer has gone from the likes of Donkey Kong to Super Mario Odyssey, a game which wilfully subverts convention in the most wonderful ways imaginable. Trends come and go but no genre has experienced quite the same meteoric rise and fall as the point-and-click adventure; this game style rode a wave of technological advancement in the ’80s by taking advantage of colour displays, high-resolution graphics and mouse-driven interfaces before capitalising on CD-ROM’s ability to supply almost endless storage for animated cutscenes, full voice acting and atmospheric soundtracks. However, after almost a decade of being one of gaming’s most popular draws, the point-and-click adventure retreated from the limelight, and only recently has it emerged to reclaim some of its past glories in a climate which, seemingly above all else, celebrates nostalgia.

Despite the relentless march of technology it’s quite rare for a video game genre to boom to the point that it becomes dominant for several years and then bust so dramatically that it falls almost entirely out of favour. Shooters have evolved over time from crude, single-screen 2D affairs to intense and immersive first-person blasters, while the humble platformer has gone from the likes of Donkey Kong to Super Mario Odyssey, a game which wilfully subverts convention in the most wonderful ways imaginable. Trends come and go but no genre has experienced quite the same meteoric rise and fall as the point-and-click adventure; this game style rode a wave of technological advancement in the ’80s by taking advantage of colour displays, high-resolution graphics and mouse-driven interfaces before capitalising on CD-ROM’s ability to supply almost endless storage for animated cutscenes, full voice acting and atmospheric soundtracks. However, after almost a decade of being one of gaming’s most popular draws, the point-and-click adventure retreated from the limelight, and only recently has it emerged to reclaim some of its past glories in a climate which, seemingly above all else, celebrates nostalgia.

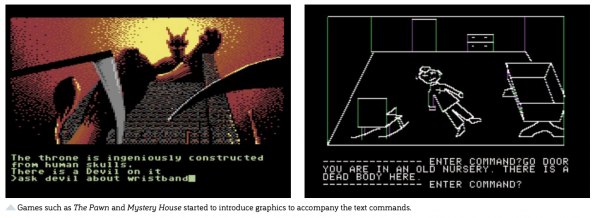

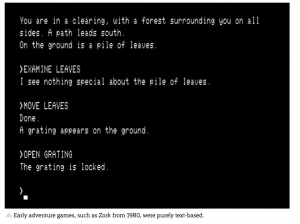

The point-and-click adventure’s origins lie in a related genre, the text adventure. In the early days of the industry the average personal computer – intended for displaying screen upon screen of dull text and numbers, lest we forget – simply wasn’t capable of producing the kind of images that could convince anybody that they were inhabiting another world. The solution was to use text to transport the player to other realms and realities, and a series of highly successful titles appeared, including Zork, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Colossal Cave Adventure. Using text not only allowed developers to overcome the shortcomings of the hardware, it also enabled them to leverage the imagination of the player to conjure up dramatic scenes and tense encounters. However, it was obvious that this genre would benefit greatly from on-screen visuals to accompany the textual descriptions, and that came to pass in the early ’80s, when titles like The Pawn, Mystery House and The Hobbit skilfully fused rudimentary pictures with words to produce a far more immersive experience. Mystery House was the work of husband-and-wife team Roberta and Ken Williams, founders of On-Line Systems. In spite of its incredibly basic vector-based monochrome visuals it was a striking commercial success for the fledgling studio, earning the couple a cool $167,000 for their efforts. Off the back of this triumph the pair would be commissioned by IBM to create a game to show off the visual capabilities of its new PCjr system. 1984’s King’s Quest showcased colour visuals, a pseudo-3D environment and even an on-screen representation of the player’s character, effectively laying down many of the point-and-click genre’s foundations, despite lacking the one thing most players would come to directly associate with this type of game: a mouse-driven interface. Instead, King’s Quest was built using Sierra’s ‘Adventure Game Interpreter’ – an engine which continued to use a text parser to interpret the player’s intentions, with movement being controlled by directional keys on the keyboard. Despite its myriad problems – the parser was imperfect and navigating the protagonist around the ‘fake’ 3D space was often a frustrating affair – King’s Quest sold well and is credited by many with establishing a template that would be copied by countless titles over the next few years.

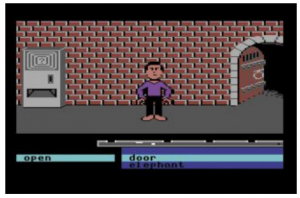

Despite King’s Quest’s success and Sierra’s other forays into the world of visual adventures, it would take a technological leap of another kind to really complete the picture. Typing in text was cumbersome and broke the flow of the game, drawing the player’s attention away from those eye-catching, 16-colour visuals. It was the 1984 release of another piece of rival hardware, the Apple Macintosh, which provided the final piece of the point-and-click puzzle. While Apple’s new machine shipped with a monochrome display, it boasted a much higher screen resolution than its rivals. However, it was the machine’s interface which was truly groundbreaking – it had a mouse as standard. Apple co-founder Steve Jobs is often credited with inventing the mouse but he actually borrowed the idea from Xerox, taking the company’s $300 three-button design and streamlining it into a single-button device which cost just $15 to manufacture. Game designers wasted no time in leveraging the Mac’s revolutionary control system and high-res screen to craft unique adventure titles; Silicon Beach Software led the way with 1984’s Enchanted Scepters, widely credited as being the first ‘true’ point-and-click adventure, but it was ICOM Simulations – founded by Tod Zipnick, who tragically passed away with Hodgkin’s disease in 1991, just as his company was beginning to become financially successful – and its ‘MacVenture’ series which really pushed the envelope. 1985’s Déjà Vu: A Nightmare Comes True!! may have adopted a first-person viewpoint but in all other respects it showcased the hallmarks of the point-and-click genre: an inventory, action verbs – such as ‘Examine’, ‘Open’ and ‘Speak’ – and the ability to drag-and-drop items. Ironically, Déjà Vu found the most success on a system that was woefully inadequate for this unique interface; it was ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1990 with low-resolution colour visuals and a simplified control system to account for the console’s lack of a mouse. The Uninvited (1986), Shadowgate (1987) and the almost inevitable Déjà Vu II: Lost in Las Vegas (1988) followed, and ICOM then branched out into the world of CD-ROM with its groundbreaking Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective series. By this point the company had been comfortably surpassed by On-Line Systems, now known as Sierra On-Line, which continued to develop its ‘Quest’ series of adventures.

King’s Quest’s initial success on the PCjr had ensured that sequels would follow, but Roberta and Ken Williams were keen to branch out from the fairy-tale setting and explore new narratives. The first was 1986’s Space Quest: Chapter I – The Sarien Encounter, a sci-fi adventure which didn’t take itself at all seriously and would set the tone for many of Sierra’s future titles. 1987’s Police Quest was less humorous but still had moments of mirth – despite the unnervingly realistic depiction of police procedure thanks to the creative involvement of Jim Walls, a retired highway patrol officer – but it was 1987’s Leisure Suit Larry which perhaps typified Sierra’s approach at the time. The brainchild of Al Lowe, Larry was a balding, poorly-dressed no-hoper whose singular goal in life was to bed as many women as possible, ignoring the odds stacked against him. The game’s visuals were blocky and crude, but its risqué subject matter ensured fame and fortune, as well as multiple sequels across computers, consoles and – more recently – smartphones. Ironically, the franchise’s reputation for lewd content has perhaps been exaggerated over time and the earlier entries are more memorable for their witty dialogue and amusing storylines than the amount of crudely-animated flesh on display. Sierra would eventually retire its ageing AGI engine and replace it with the ‘Sierra Creative Interpreter’, or SCI for short. 1988’s King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella used SCI to deliver massively improved visuals, and the game was also one of the first PC titles to support sound card hardware.

However, by this point the company had some serious competition in the realm of point-and-click adventures from a company founded by the man behind Star Wars, George Lucas. Lucasfilm Games was established in 1982 and initially focused on intense action titles – such as Ballblazer, Rescue on Fractalus! and Koronis Rift – and it wasn’t until 1986 that the studio ventured into the genre it would come to shape and dominate. Labyrinth: The Computer Game was based on the movie starring the late rock star David Bowie, and used word wheels – one for verbs and one for nouns – to avoid the usual confusion generated by text parsers. Hitchhiker’s Guide author Douglas Adams also contributed to the design of the game, which, despite its initial critical and commercial success, has been forgotten over the years – an unjust fate, since Labyrinth inspired Lucasfilm’s next foray in the genre and was one of the most influential point-and-click titles ever made.

However, by this point the company had some serious competition in the realm of point-and-click adventures from a company founded by the man behind Star Wars, George Lucas. Lucasfilm Games was established in 1982 and initially focused on intense action titles – such as Ballblazer, Rescue on Fractalus! and Koronis Rift – and it wasn’t until 1986 that the studio ventured into the genre it would come to shape and dominate. Labyrinth: The Computer Game was based on the movie starring the late rock star David Bowie, and used word wheels – one for verbs and one for nouns – to avoid the usual confusion generated by text parsers. Hitchhiker’s Guide author Douglas Adams also contributed to the design of the game, which, despite its initial critical and commercial success, has been forgotten over the years – an unjust fate, since Labyrinth inspired Lucasfilm’s next foray in the genre and was one of the most influential point-and-click titles ever made.

1987’s Maniac Mansion was conceived by Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick, the latter having worked as an artist on Labyrinth. The two bonded over their affection for B movies and oddball humour, and decided to create a game which reflected these shared passions. Maniac Mansion’s non-linear progression, multiple characters and detailed visuals made it instantly memorable, but perhaps its most enduring legacy is the introduction of SCUMM – also known as ‘Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion’ – a fully mouse-driven interface which gave the player a set of input commands as well as the ability to interact with and combine objects in their inventory. SCUMM would be employed in several subsequent Lucasfilm adventure games and inspired countless copycat titles which adopted almost entirely the same approach. While its interface became practically ubiquitous, Maniac Mansion’s design was equally important; unlike many of Sierra’s adventure games – in which the player could die simply by picking up the wrong object – Maniac Mansion established what would become a core tenet of Lucasfilm’s point-and-click ethos. Gilbert reasoned that punishing the player for simply trying things out was needlessly brutal and sadistic, and he made attempts to ensure that his games were free from situations where the player would die or end up being stuck in a dead end because they hadn’t collected the correct item. The onus would be on encouraging players to experiment without fear of reprisal, and this opened the door for the wild and often obtuse logic puzzles that became part of the company’s DNA. After finding success on the Commodore 64, Maniac Mansion was ported to a wide range of other systems, including the Nintendo Entertainment System – marking one of Lucasfilm’s first big steps into the world of console gaming. The NES port created a whole new legion of fans, although Nintendo’s draconian policies regarding software content forced significant changes to be made to secure a release.

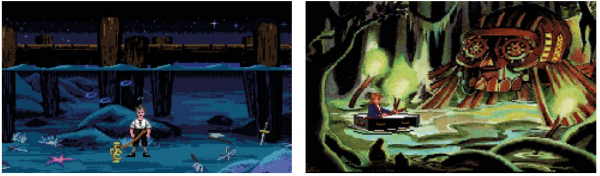

1988’s Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders was the second game to utilise the SCUMM game engine, and boasted a very similar style of graphics and humour, while the following year’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure leveraged the fame of the popular Hollywood action series to create a rip-roaring quest which, for once, dialled back the zany humour. 1990’s Loom arguably went a step further, presenting the player with a fantasy storyline so earnest it could have leapt from the pages of J.R.R. Tolkien himself. Loom is also notable for forgoing the typical SCUMM interface and instead using magical four-note tunes to solve puzzles and interact with the environment. Loom took the point-and-click genre in an interesting new direction, and had it been released in any other year it perhaps would have gained more recognition and lasting fame. Unfortunately, Loom was joined in 1990 by fellow Lucasfilm release The Secret of Monkey Island, not only one of the most famous point-and-click games ever made but also arguably one of the most beloved titles in the history of interactive entertainment; it’s fair to say that it rather overshadowed its stablemate.

Ron Gilbert, aided by Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman, set the adventure on a fictional Caribbean island and was heavily inspired by Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean theme park ride. What made Monkey Island truly unique was its humour; the game lampooned the common preconception of pirates and took every opportunity to poke fun not only at the setting and its characters, but also the player. However, one thing Gilbert was not prepared to do was punish people for making the wrong move; Monkey Island continued the good work seen in Maniac Mansion and encouraged experimentation. The game’s combat section was based around insults rather than trading actual blows, and this would become one of the title’s most famous elements; acclaimed sci-fi author Orson Scott Card – the brains behind the seminal novel Ender’s Game – contributed some of the more cutting insults during a visit to Skywalker Ranch. Dialogue trees for conversations were also introduced, and the SCUMM engine was refined over its previous iterations. Although the original PC EGA version was limited to just 16 on-screen colours, the later VGA edition gave the designers 256 hues to work with, which resulted in some particularly striking hand-drawn close-ups for certain characters. Despite its enduring fame and incredible influence, The Secret of Monkey Island wasn’t a massive commercial success at the time of its release. Development of the sequel began before the original was even published, and had the studio waited to see the numbers we may never have gotten a sequel. Thankfully, that particular timeline never occurred and 1991 saw the release of Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. The evolution that had taken place between the two games was obvious: the 256-colour VGA graphics, while still limited to just 320x200 pixels, possessed astonishing detail and created a truly evocative atmosphere. Whereas the original game – even in its enhanced VGA iteration – had a rather basic visual style which used few colours, Monkey Island 2’s gorgeous hand-painted artwork made its locations spring to life, and the characters themselves boasted superior animation and detail. The widespread adoption of sound cards on PCs meant that audio could be refined to the point where music would react to on-screen events; the iMUSE system – created by Michael Land and Peter McConnell – allowed tracks to blend seamlessly into one another rather than ending and beginning abruptly. The amusing and witty writing so prevalent in the first game was turned up a notch too, and Monkey Island 2 became one of the year’s stand-out PC gaming hits – a fine way for the newly-rechristened LucasArts to kick off a new period in the company’s history.

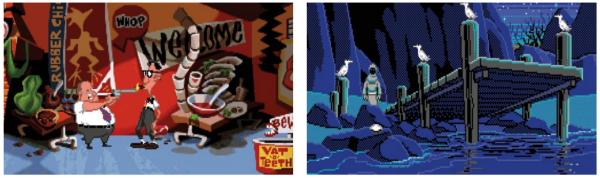

1992’s Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis toned down the humour while presenting players with three possible pathways through the adventure, and sold over a million copies across all of the formats it was published on. Visually similar to Monkey Island 2, the game tried to create realistic representations of human characters – something which could not be said of 1993’s Day of the Tentacle, a sequel to Maniac Mansion which used a sumptuous cartoon-like art style that would become a signature look for LucasArts games over the next few years. Inspired by Looney Toons animated shorts (apparently the legendary Chuck Jones even visited the team during development to provide feedback and ideas), the game’s bold visuals allowed for more expressive characters which in turn enhanced the already side-splitting level of humour. The in-game animations alone took a year to create, and a lengthy introduction sequence set the scene at the start of the adventure – a feature which would become a prerequisite as CD-ROM technology gave game developers so much storage that they struggled to fill it with anything more meaningful than music and FMV sequences. To release a game as good as Day of the Tentacle in a single year was remarkable enough, but what’s truly stunning is that LucasArts also published Sam & Max Hit the Road in 1993 as well. This dog and rabbit duo were the stars of a comic created by artist and LucasArts employee Steve Purcell, who’d previously contributed to Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, both Monkey Island games and Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts saw Purcell’s comic book creation as a viable franchise and offered him the chance to turn the property into a point-and-click adventure. Like Day of the Tentacle, Sam & Max used a bold cartoon style which made the whole thing feel like an interactive animated movie – a feeling that was reinforced by the fact that it was one of the first games to utilise CD-ROM technology for full voice acting. LucasArts had created enhanced CD versions of past titles, like Loom and Monkey Island, but had used the space for improved music instead of vocal tracks. Elsewhere, the innovations came thick and fast; the SCUMM engine was comprehensively overhauled, removing the verb tiles at the bottom of the screen and bonding them to the mouse cursor, where they could be cycled through using the right-hand mouse button. The inventory was also relocated to its own screen. The end result was more real estate for the gorgeous artwork, and it also made locations feel bigger and more expansive. Finally, the conversation trees were altered so that players could select an icon representing their response – a change that prevented upcoming punchlines being ruined because you could read them before the characters delivered them.

Plenty more where this came from – we’re only up to 1992! Stay tuned next week for the concluding installment of “The history of point-and-click adventure games” from The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games, followed later by a pair of interviews with beloved genre legends.

(Note: As an affiliate partner, Adventure Gamers gets a small percentage of proceeds from every copy of the book sold through our links. This is no mercenary exercise, however. We’d be promoting this book anyway: it’s THAT good.)