Conquests of the Longbow – An excerpt from The Sierra Adventure: The Story of Sierra On-Line

Following the first part of our month-long exploration of The Sierra Adventure: The Story of Sierra On-Line, author Shawn Mills takes us behind the scenes of one of Sierra's less-heralded but no-less-exemplary franchises with first-hand contributions from lead designer Christy Marx and programmer Richard Aronson. This excerpt about the production of The Legend of Robin Hood represents just one game of many included in Shawn's 361-page book based on interviews with over fifty key players at Sierra, ranging from management to producers, artists, designers, musicians, and marketers, all telling the story of Sierra in their own words. The book is available now for purchase in hardcover, paperback, and eBook formats.

Conquests of the Longbow: The Legend of Robin Hood

Like Conquests of Camelot before it, the broad concept for Conquests of the Longbow: The Legend of Robin Hood came from Roberta Williams. “I was in the earliest stages of thinking about a game based on Greek mythology using goddesses,” Christy Marx says. “I was aware that a number of Robin Hood movie projects had been announced, but when Roberta mentioned them to me I didn’t pay attention. It didn’t relate to what I was thinking about.

“A day or so later after the first mention, Roberta said to me, ‘I had this dream last night that you were doing a Robin Hood game.’ I suddenly realized that what she was really doing was dropping hints that they wanted me to do a Robin Hood game.”

What exactly is the Robin Hood story? This was the question Christy had to grapple with when she started working on her second game for Sierra. As is common with legends hundreds of years old, the telling of the tale has changed over time, so the first thing Christy did was to follow the story as far back as she could.

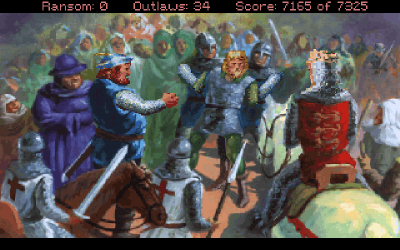

Researching the earliest accounts of Robin Hood and the ballads of King Richard helped Christy form the main premise in her mind. The story of Conquests of the Longbow would be one of Robin trying to raise the ransom to free King Richard, who had been betrayed and captured by King Leopold of Austria on his way home from the Third Crusade in 1192. While this was to be the main plot, extensive work also went into developing the character of Maid Marian and the love story that would unfold.

Researching the earliest accounts of Robin Hood and the ballads of King Richard helped Christy form the main premise in her mind. The story of Conquests of the Longbow would be one of Robin trying to raise the ransom to free King Richard, who had been betrayed and captured by King Leopold of Austria on his way home from the Third Crusade in 1192. While this was to be the main plot, extensive work also went into developing the character of Maid Marian and the love story that would unfold.

While the person of Robin Hood may actually be a myth (even scholars can’t be certain), the locations involved in his folktales are all real, and that was an area that Christy could research and portray accurately in the game.

“I went so far as to purchase a huge book that reprinted land maps from medieval England so that I could make Watling Street, originally an ancient Roman road, as accurate as possible (traces of it remain as a major highway in England today). I contacted the museum at Nottingham and purchased useful reference materials from them, including a large poster of what the castle originally looked like,” Christy says.

Richard Aronson had recently been installed as a lead programmer at Sierra. His first game was Conquests of the Longbow and he recalls the collaborative way in which Christy worked.

“It’s my first week there. [SCI systems developer] Bob Heitman comes up to me and says, ‘I’m concerned about the amount of art called for in this game. I asked the lead artist for an art list, I asked the producer for an art list, and neither of them had one,’” Richard remembers. “‘I want you to work out the storyboards and build a list of all the animations and backgrounds required for this game so we have an idea of just how much it’s going to cost.’

“So my first three weeks at Sierra, I was not doing any programming at all. The net result was that the design was about 50% larger than the game was budgeted for. The way we resolved it was by reusing rooms. You would go into the same room on a different day; that lightened up the art load, but programmers had to code the rooms in two different days. So it was still a problem. That’s part of why it was such a big game, because we worked really, really hard to get it right.”

Another issue occurred during the climax of the game, where Christy had designed a sequence that Richard didn’t believe would be possible to produce in the SCI engine: “Originally the combat was supposed to be one of the first real-time strategy games in Christy’s design, but I looked at the process of moving two hundred man-sized things on a screen in the VGA world and how much processing power that would take and said, ‘No, we can’t possibly implement that in this system. We don’t have the processing power.’

“So eventually she just handed combat over to me and I wrote five plans and she edited them and rewrote several. Each of Robin’s men would present a plan and I would resolve that with the number of men you had alive. Little John would always have terrible ideas except for the last one, which is the best one. Part of your score is based upon how many men you had; politically King Richard is much more likely to reward Robin of Loxley if he has a band of fifty behind him than if he has a band of six behind him. That indicated loyalty and leadership and that he’s a strong guy and so forth. It fit within the game sequence.”

“So eventually she just handed combat over to me and I wrote five plans and she edited them and rewrote several. Each of Robin’s men would present a plan and I would resolve that with the number of men you had alive. Little John would always have terrible ideas except for the last one, which is the best one. Part of your score is based upon how many men you had; politically King Richard is much more likely to reward Robin of Loxley if he has a band of fifty behind him than if he has a band of six behind him. That indicated loyalty and leadership and that he’s a strong guy and so forth. It fit within the game sequence.”

Richard wound up doing a lot of the design of the Nottingham Fair himself. “Part of why Sierra hired me was I had ten years’ experience working and eventually leading workshops at the Los Angeles and San Francisco Renaissance Faire, so I had a very strong background in medieval history. My degree is in English history. When [Christy] got around to that section, she said I could design all the interactions, which I did and then she just edited them. Christy was very collaborative in that way, and so were Corey and Lori [Cole]. Others were less so. It varied.”

An important area in which Richard Aronson left his mark was insisting on a way to help people with disabilities play Sierra’s games. “My brother-in-law was a quadriplegic. He used to play Sierra games with a wooden stick strapped to his forehead to hit the keys. Then he hit one of our minigames or arcade sequence and he’d have to wait until the nurse beat the minigame for him to continue,” he says.

“There were dozens of people in just his convalescent hospital playing these games and they all had the same problem. So when I started at Sierra, I said, ‘You know what? A lot of people play our games that have these other issues. We should have a bypass [where] you beat the [minigame] with a score of zero, but you can progress, for people who are physically challenged. We should make sure we have a text display option on all our games for people who are deaf. That should be important.’ These are now somewhat standard in the industry but I’m proud of that because I think it helped a lot of lives.”

It was during the quality assurance rounds that Richard introduced another new idea to Sierra: crediting all the testers. “Back then, the lead programmer got to write the About screen,” he explains. “I wrote the About screen and I sent an email over to the lead QA [tester] and said, ‘I want the names of all the testers’ and they said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘I want to put them in the About screen’ and they said, ‘We don’t do that’ and I said, ‘Why not?’

“About a week later I got called into Ken Williams’s office for a meeting on that. He said, ‘Why are you doing this?’ and I said, ‘First of all, it’s free. It’s not going to add any extra disk space. Second of all, it’s going to tell the world we test our games. Third of all, I’ve written a couple of really good jokes [to include in the credits]. And finally, every single beta tester is going to want a copy of the game. They’re going to show off. They’re going to feel proud and invested for working here. You motivate your employees, it doesn’t cost you anything. You get to improve your PR with the world. Why don’t we do it already?’ Ken says, ‘Okay!’ So, we did it and it was well received.”

“About a week later I got called into Ken Williams’s office for a meeting on that. He said, ‘Why are you doing this?’ and I said, ‘First of all, it’s free. It’s not going to add any extra disk space. Second of all, it’s going to tell the world we test our games. Third of all, I’ve written a couple of really good jokes [to include in the credits]. And finally, every single beta tester is going to want a copy of the game. They’re going to show off. They’re going to feel proud and invested for working here. You motivate your employees, it doesn’t cost you anything. You get to improve your PR with the world. Why don’t we do it already?’ Ken says, ‘Okay!’ So, we did it and it was well received.”

The testing was done in shifts, with a team of testers focused on compatibility issues during the day and another team looking for game bugs at night.

“Most of our testers worked in the daytime and then there was another team that only worked at night because, when you’re in crunch mode, you’d do a build before you go home at the end of the day. They’d work on them all night on machines that were very standard, so therefore there’s not compatibility issues; it’s going to be game bugs that are found. Then you show up first thing in the morning and you’d have your list of bugs. It’s a very efficient way to work,” Richard describes.

“So I’d list everyone. Executive producer Ken Williams always comes first. Then I’d say QA team one. Long list. QA team two. Long list. Then these people, long list, fixed the bugs that were found in the night. So that worked out really well and became part of the standard.”

Conquests of the Longbow: The Legend of Robin Hood was released in December 1991 and went on to become another bestseller for Sierra. It was Christy Marx’s last game released with Sierra.*

*It was not the last time she worked with Sierra, however, as she came back a few years later to help design the unreleased Babylon 5 game.