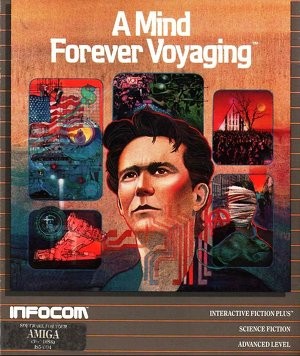

A Mind Forever Voyaging flashback review

Politics are a rare foundation for a game. How many political-centred games can you name? For me, it's depressingly few. And those I can think of have nearly all been made during the indie game boom of recent years. Yet back in 1985, Infocom released A Mind Forever Voyaging, an unabashedly political text adventure, at the time unique in both its subject matter and game design. On this fact alone, the game is remarkable. But even disregarding the context in which it was written, it is a well-made game – flawed, yes, but vividly conceived and fascinating to experience even 30 years later.

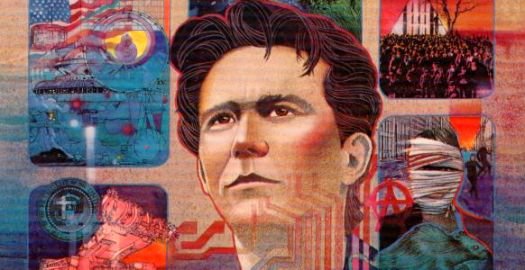

You play as PRISM, an artificial intelligence unit who is suddenly awakened to the fact that he is a computer, after unknowingly living 20 years of his life in a simulation as Perry Simm. He was awoken so that he could be used to experience and then report on the effects of "The Plan for Renewed Purpose", a strongly right-wing plan put forth to revitalise the newly-formed USNA's (United States of North America) collapsing economy and society. You are told to re-enter the simulation and record footage pertaining to The Plan's effect on Perry's fictional hometown of Rockvil, as seen over a period of several decades.

In effect, the game becomes an interactive polemic against American Republican party politics, in particular the Reagan government. But what's curious is just how not-dated it is. I would even say its points are more relevant today than in the 1980s. Richard Ryder, the fictional Senator who proposed The Plan, is the synthesis of typical right-wing ideas at the time and possesses the rhetoric skills and popularity of then-President Reagan. The Republican Party has by no means changed course since Reagan, though. And with the emergence of real-world Senators like Ted Cruz, Senator Ryder becomes an even more relevant character, one whose proposal of dramatic tax cuts, talk of “flim-flam bureaucracies”, disdain for foreign aid and dubious interpretation of the Establishment Clause will doubtless have a strong familiarity.

When it comes to gameplay, A Mind Forever Voyaging also seems modern and innovative. Yes, it's a text adventure, which some may wrongly view as self-evidently antiquated. But it's also a largely puzzle-less, combat-less story that could almost be compared to games like Gone Home or Dear Esther, but with a larger and more open world to explore. It is a bit more intricate than that, however – as the player character is a computer, you have various modes and controls that give the gameplay greater complexity and make you feel like more than a passive observer. This contributes to the sense that the game was ahead of its time, and I couldn't help but notice the prescience of its design, mostly eschewing puzzles and traditional gameplay in favour of something more “literary”.

Perhaps more importantly, the gameplay makes for an engaging experience, regardless of how innovative it was. Providing a vast and changing world allows players to experience a linear narrative in a non-linear way. It is inevitable that certain events will happen, and that societal change like increasing poverty will occur, but you are given the freedom to explore the effects of these changes and discover many of the scripted events that take place in your own way, gathering evidence and piecing together the narrative. While playing, I almost thought of myself as a journalist, or a historian perhaps – not just a player or reader. And not just a sentient computer following instructions either: PRISM is a being built to fulfil the role of a researcher.

This, of course, wouldn't be compelling without the world and story themselves being interesting. Fortunately, A Mind Forever Voyaging is a game with a huge map and a plethora of details and occurrences that create not only a fascinating backdrop, but a level of replayability that is otherwise rare in adventure games. You could stumble into the raids conducted by the newly-formed Border Security Force, take a ride along the Tube, or visit the increasingly spartan supermarkets. Alternatively, you could just sit back and read the news broadcasts detailing the actions of white terrorist groups in South Africa or Senator Ryder's empty rhetoric on problems of crime and education. This all makes for an immersive setting worthy of several hours – if not more – of exploration.

Nonetheless, the gameplay is not without its problems. The large world, for which there is a very unspecific map that comes with the game, can be confusing to navigate. Like most text adventures at the time, it has a few too many non-reciprocal winding paths and will probably require most players to do some manual mapping. This isn't too bad, though, especially considering that some homemade maps can be found online, and free computer programs do exist to help map out Interactive Fiction (I recommend Trizbort). It's certainly an endurable sacrifice for such a large and vivid world.

More irritating is the fact that to enter this world, you'll have to get past the game's pesky copyright protection. Whenever you wish to begin simulation mode, which you will do frequently, an access code will be requested, at which point you'll have to whip out the Class One Security Mode Access Decoder, a rotating paper wheel that originally shipped with the game. (Alternatively, if you buy the iOS version, you get a virtual paper wheel to use.) Don't worry if you no longer have access to the decoder, however, as you can easily find a table online in which some poor soul has transferred all the access codes. So while annoying, this requirement never becomes game-breaking.

The game also shows its age through its size restrictions. A Mind Forever Voyaging was the first of the “Interactive Fiction Plus” line of Infocom games, which boasted a whopping 256k limit, but even this proved not to be enough. The prose ends up being relatively plain – perfectly serviceable but never really remarkable. Apparently the game only had 10 bytes to spare, not even enough for one more sentence, which would at least partially explain some of the problems with the writing. This forced restriction may have played a part in making the script more sharp and focused, but mostly it means that people and objects are sometimes given inadequately brief and matter-of-fact descriptions, if a description was implemented at all. It would have been nice to hear about the atmosphere and feeling of the simulator locations, not just a sentence or two saying, for instance, “You are standing in the lobby of a wide sprawling building containing a cafeteria, a bookstore, an auditorium, and offices for student activities. The street is southwest of here.” This is a fairly sizeable problem for a game with notably high literary aspirations.

Fortunately, the text parser has far fewer setbacks. Infocom's parser was way ahead of its time technologically, and it still forms the foundation for most modern parser-based Interactive Fiction (IF). So needless to say, the parser holds up remarkably well. It isn't that much different in A Mind Forever Voyaging compared to earlier Infocom games; by this time a few more helpful commands and shortcuts, like 'x' for examine, were included, but otherwise the difference is negligible. Obviously, as nearly three decades have passed since its release, there are modern conveniences that those familiar with IF may well miss: the lack of an 'undo' function, for instance, or the absence of a 'go to' option to aid with navigating the game's expansive map. But these are all minor grievances, and on the whole gameplay should be largely absent of frustration, a testament to the famed quality of Infocom's parser.

A major grievance can, however, be had with the game's distinct lack of nuance. I mean this in the sense that everything feels so black-and-white, and the politics feel so unbalanced and uncompromising. There is the small, almost negligible suggestion that The Plan was a response to problems of a liberal or other non-right wing government, perhaps akin to the Carter administration. But overall the game offers a dichotomy of viewpoints, one clearly right and one clearly wrong. There is the wholly dysfunctional hell of neoliberalism and neoconservatism, and there’s the marvellous utopia of American progressivism. Even if you sympathise with some – or all – of author Steve Meretzky's views, the arrogance and seeming unwillingness to concede the problems of this singular ideology can be irritating, even off-putting.

Another clear problem is that the characters in the game are relatively superficial, often having no more than one line of dialogue. Even Senator Ryder is not an interesting character, just a generic caricature of Reagan. But despite lacking an emotional investment in these characters, Meretzky still manages to create some vividly frightening and moving moments. For fear of revealing too much of the plot, I'll just say that the moral decay of society, including increased religious intolerance, barbarism and state restrictions on freedom, lead to many events that should in any person evoke disgust and sadness. And the pace of the game, slowly revealing these changes from their embryonic form in political policies to mass societal change, makes it even more effective.

The third and final part of the game is a bit of a departure from the rest of the adventure. This is where you'll find the game's one puzzle. And it's pretty good, provided you've taken it upon yourself to explore all of the controls available to PRISM beforehand. Otherwise – especially considering it's a timed puzzle – it has the potential to be quite frustrating. But it is cleverly designed and a key part of the narrative, not just put in for the sake of having a puzzle.

On a purely visual level, there aren't any graphics (apart from a crude Rorschach test), but unlike in 1985 there are now multiple ways to play the game, some of which allow for a great degree of typographical variations. I personally used Gargoyle (though I recommend Mac users try Spatterlight), a free interpreter for a variety of Interactive Fiction file types, both old and new. The advantage of this is an ability to change font types, sizes, colours, etc. But if you want to go retro you can easily play this game in DOSBox. There is also an iOS app, Lost Treasures of Infocom, that allows you to purchase and play the game that way, as well as most other Infocom text adventures.

Part of me is tempted to use the patronising cliché that A Mind Forever Voyaging is remarkably good “for a game.” There's no getting around the fact that the prose is mostly utilitarian, the characters are markedly thin, and the ideas presented often lack nuance. Infocom boldly compared the game to Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four, comparisons which only highlight these complaints further. But in the end, I feel its best aspects are in fact because it is a game. The great sense of exploration and non-linearity make you feel more like a historian researching for a book than a mere reader and player, curiously gathering evidence to evaluate The Plan for Renewed Purpose, all in a clearly-imagined and at times frightening world that seems more contemporary now than when it was written. For those who enjoy games heavy on exploration or with a political bent – or just want to experience a fascinating moment in gaming history – you should definitely check it out.

WHERE CAN I DOWNLOAD A Mind Forever Voyaging

A Mind Forever Voyaging is available at:

We get a small commission from any game you buy through these links (except Steam).Our Verdict:

Infocom’s A Mind Forever Voyaging was an innovative and bold game in its time, and though it never quite achieves its lofty ambitions, it does come admirably close.

_capsule_fog__medium.png)