Exploring The Cave with Double Fine’s JP LeBreton and Chris Remo interview

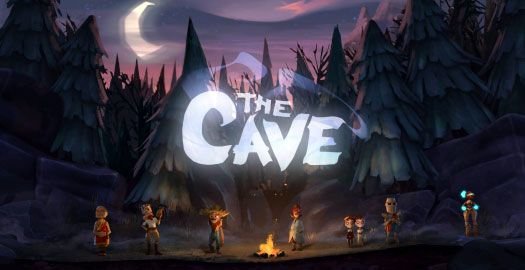

When Double Fine and Sega announced The Cave last spring, many fans of Ron Gilbert’s adventure games were skeptical. The minute-long trailer showed cartoon characters running around and jumping in what appeared to be a traditional side-scrolling platformer, suggesting that the father of Maniac Mansion and Monkey Island had forgotten exactly what an adventure game is. When I first saw that trailer, I was uncertain, too. But after I sat down with Ron and he described the game and showed me an early portion, I was persuaded. The Cave, while not an “old school” adventure in the SCUMM tradition, is guided by the same principles of exploration, puzzle solving, and humor present in all of Ron’s previous adventure outings. And, as demonstrated at a recent press event, it brings something entirely new to adventure gaming: local multiplayer.

Wait… multiplayer? you might be thinking. No! This is even less of an adventure game than I thought! To be clear, The Cave’s multiplayer has nothing to do with competition or facing off against an opponent. It’s a means for two or three players to work together, all on the same computer or console (not over the internet), with each player controlling a member of The Cave’s three-character party to solve puzzles cooperatively. Think URU: Ages Beyond Myst, but the person you’re collaborating with is right there in your living room.

Setting for Double Fine press event in San Francisco

Just like in Gilbert’s first adventure, Maniac Mansion, The Cave begins with players selecting three characters from a line-up of seven. At the press event, these characters had been predetermined: the Hillbilly, the Monk, and the Adventurer. Each character is assigned to a direction button and a graphic at the bottom of the screen reminds you which character is linked to which button. (We played on an Xbox 360; on PC the controls will be mouse-driven.) Using the D-pad, one player can switch between characters or pass control to another player. The camera follows the currently selected character, leaving the others behind if he/she wanders off, then pans back when a different character is selected to help you understand where certain areas are in relation to others. This allows you to freely explore a relatively large area without having to worry about losing your companions.

I sat down with another journalist to tackle a portion of the game where the party tries to break into a carnival to impress a girl the Hillbilly has a crush on. After some initial awkwardness about who should “go first,” we each spent a few minutes running around in different areas of the cave, and a bevy of puzzles in need of solving began to emerge from its depths. The sequence involved cheating at a series of carnival games—surviving a dunk tank, predicting which color the wheel of fortune would land on, fooling a canny carnie into guessing your weight incorrectly, etc.—in order to earn enough tickets to win a prize for the Hillbilly’s love interest. Some puzzles could be solved by any one character or by any two working together, while others required a specific character’s special power (such as the Hillbilly’s ability to breathe underwater longer than the others). Each solution relied purely on exploration, deduction, and logic; in the portion I played, there was absolutely no dexterity or reflex required as in a puzzle-platformer like Braid or Limbo.

Here’s the beautiful part: my partner and I solved these puzzles together. Sometimes a few minutes would pass where only his character was visible on screen. When he wasn’t sure what to try next, I would take control for a few minutes and check out a different part of the cave. But all along we were having a dialogue about what we should try next. He saw some solutions before I did. I figured out where to use some items before he did. Once or twice, we had the same revelation at the exact same time and shared an “aha!” moment. We discussed what to do and laughed or groaned together when the attempts didn’t pan out. (It is possible to die in The Cave, but these tend to be humorous, cartoony deaths and you immediately respawn in the same area, no harm done.) In the end, we solved the chain of puzzles that were blocking entry into the carnival as a team—an experience I haven’t had since I was fourteen years old playing The 7th Guest with my best friend, side by side at my parents’ computer.

Layout of The Cave's Hillbilly level

For those who prefer to adventure alone, don’t worry: The Cave’s multiplayer is completely optional. But after glimpsing the potential for collaboration that Ron and his team have built into the game—not to mention the pure puzzle-solving gameplay—I’m not only confident that The Cave falls into the adventure category, but I also know that it brings something brand new and very special to the genre. (Kind of like Maniac Mansion, the very first point-and-click adventure game, did back in 1987.) A lot of fans may not be convinced until they’ve played it for themselves, but luckily that chance will come soon, as The Cave is scheduled to release for PC, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and Wii U later this month.

Still glowing from my hands-on play session, I sat down with designer JP LeBreton and writer Chris Remo (a former Adventure Gamers staffer) to talk about what it’s like working with Ron Gilbert, how The Cave’s puzzles and story came to be, and what they, as longtime adventure gamers themselves, think of the non-traditional gameplay.

Emily Morganti: What’s it like being a fan of Ron Gilbert’s, and now working on a game with him?

Chris Remo: It’s been awesome. I think about this a lot because [Double Fine studio head] Tim Schafer was actually one of the first people I met in the games industry, like a decade ago, and then the first game I ever worked on was Psychonauts as a tester. [Double Fine]’s not the first studio I worked for, but now working for Tim’s studio and with Ron on a game has been really crazy, because those are guys whose names I knew when I was a kid. One of the greatest things about playing LucasArts games back in the day was that they always put the designer’s name on the box. So Monkey Island would have Ron Gilbert’s name on there, and Full Throttle would say “a heavy metal adventure by Tim Schafer.” So I’ve known those guys’ names for 20-plus years. A lot of games, at the time, you wouldn’t know the people who worked on them. So now being in a position where I work for Tim’s company on a game with Ron Gilbert—it’s out of control.

Emily: If you could tell your ten year old self—

|

A very surprised Chris Remo

|

Chris: I would have no conception of what that would mean. If I had told myself that—well, first of all I’d be confused as to why a version of me was present and talking to myself, but assuming I had the stoicism to get past that, I would still have no conception of what it would mean to say “I work [in game development]” because I never knew game development was a thing that people did. I didn’t actually grow up wanting to make games. That was never an intention of mine. It was never something I even considered as a thing that was done. It wasn’t until I was out of college that it was something I even thought about. So when I started working at Double Fine [as community manager], at a certain point Ron just came up to me and said “Hey, do you want to help write The Cave with me?” And I said okay. [laughs] So that was cool. ‘Surprising’ is a better word.

JP LeBreton: I guess I played Maniac Mansion, probably not quite 25 years ago, but pretty close to that. So a good 20 years of my life or so I’ve known Ron Gilbert’s name… well, I’m sure I learned who he was back in—

Chris: The Adventurer.

JP: Well, yeah! I probably did, although he might have been gone by the time The Adventurer started coming out.

Chris: That’s true, actually. I think you’re right.

|

A much more composed JP LeBreton |

JP: That started in like ’92 or something. Anyway. [clears throat] Ron Gilbert existed as a concept for me, for many years. And then I actually started learning more about game development and considering it as a career, and then I ended up in game development. So I guess my development as a player of games and as a game developer has had a few different phases over the years, but adventure games were definitely the first major thing, playing Maniac Mansion on the Commodore 64, and a lot of the definitive LucasArts games on the PC. And then I got into Doom and Quake, and started making maps for that, and Half Life in the late ’90s, and then I kind of got a job—my first job in the industry—on the basis of that stuff.

Then fast forward several years, I worked on the BioShock games, but I was looking to make a move and find a cool place, and I was looking at Double Fine. Ron needed a designer for his new secret project, so I was like, “That sounds awesome, I wonder if I could actually design an adventure game?” Because I don’t think, technically, I’d worked on one before. So the part of my brain that knew a bunch about game design, and then the much older part of my brain that played adventure games and appreciated them and remembered them fondly—The Cave was all about mashing the two of those together and saying, “Okay, I’m a game designer but I’m working on an adventure game. What’s that like?” So for those first several months that Ron and I and [animator / designer Dave Gardner] designed all of the puzzles, that was a crazy experience.

Emily: What did you have to do to get hired? Did you buy a present for Ron?

JP: No, I didn’t resort to bribery or anything. I was at 2K Marin before this, and I applied and then we did the first preliminary interview where I got to meet Ron and Tim; I’d never met them before. And then I had a follow-up interview scheduled that was supposed to be like “the big interview” where I’d meet a lot of the team, and I actually ended up in the hospital like, the day before, with appendicitis.

Emily: So they hired you out of pity?

JP: I like to think so. [laughs] Anyway, it all worked out. It was pretty conventional… I mean, I guess I’d been making games for 12-plus years at that point, so I was just able to say, “Hey, I’m a game designer, I’m legit. I’ve worked on this and this before.” And the other usual interview process where you talk about stuff and try not to embarrass yourself. So yeah, I guess they liked me enough to bring me on, and now I’ve been at Double Fine for coming up on a year and a half, and it’s been fantastic. I adore working there; I’m leading a project for Amnesia Fortnight, that’s crazy, and I’m just working with fantastic, awesome people. And working with Ron was a total pleasure.

Emily: For this game, I wonder if not being an adventure game designer was a positive? Maybe Ron’s approach to this game was different than it might have been for a Monkey Island-style game, since The Cave is not a traditional adventure game?

New Ron Gilbert adventure... New Grog!

JP: I think he was looking to do things differently, which is cool and commendable. There are other people who have been making games as long as he has who are sort of more set in their ways. But I think one thing about Ron’s designs, like the first two Monkey Island games and Maniac Mansion… his initial decision to make Maniac Mansion an adventure game was sort of a considered decision. … He’s always brought a game designer’s rigor to adventure game design. There’s other schools of adventure game design that are more arbitrary, or alternately—and this isn’t a bad thing at all—more storytelling focused. I think a lot of the design work that we did on The Cave was about really thinking about it. Even though it is an adventure game, and so all of the little interactions you do are special cases and very quirky logic-type things, we still tried to make it make sense, because that’s honestly a big part of making a game like this playable.

People have to be able to walk through that deductive process and come to conclusions naturally, without having to read the designer’s mind. When people talk about bad adventure game design, it’s always like, “Oh, I would have had to read the designer’s mind to know that.” And you’ll see when you play The Cave—well, you can make up your own mind about it—but we did try to think through it a lot. And the other thing we did was playtest it a lot, and that was something that Ron definitely pushed for, being able to get people in both from outside the team but within Double Fine, and also people from outside the studio, have them come in, play the game, and watch them. The way that these work is you just have to sit down and shut up and watch them play the game, and if they struggle with something—

Chris: It’s a very weird atmosphere.

JP: Yeah, because you can’t give them a hint, and you certainly can’t… you’re a terrible designer if you say, “Oh, well, you’re playing it wrong.” Because the whole point is that you’re seeing your ideas’ first contact with reality, and that’s tremendously important.

Chris: It doesn’t matter how intuitive you think anything is, ever.

JP: Intuitive doesn’t actually mean anything in the context of game design.

Chris: Those assumptions will all just get torn apart instantly, as soon as someone sits down at the game.

Emily: Personally, I think seeing how somebody approached it, and then coming up with a way to help them approach the puzzle, is a good thing to do.

Chris: Absolutely. With adventure game design, since puzzle solutions are all discrete, they all have to be individually supported for the most part. Seeing a common route people will try to take that makes sense once you see it attempted—especially if more than one player tries it, if you see it coming up often—you can then go back and support that. Especially in The Cave, where we have these very different characters with different abilities, sometimes players will happen upon perfectly reasonable solutions to puzzles that we didn’t necessarily support right from the start. And some of that stuff has ended up folding back into the game design.

Emily: What was the process of coming up with puzzles? I’m specifically thinking about the multiplayer, how so many of these puzzles require working together. Did that change the process of designing them at all?

Chris: Real quick, to preface the answer, none of them actually require working together with another person, although a lot of them require multiple characters. But one person could do that.

JP: Yeah, we knew from the start that we would support single player with character switching, and pretty much anything we could think of works for a single player who can switch between all three, or [two or] three human players each controlling a character. So we were doing traditional adventure game puzzle design, but then we would have to think, “Okay, are other players doing enough here? If I wanted to just solo this with one character, would I be able to do that?” We would do that within the course of a single design meeting, we would go in and say, “Here’s what the puzzle is, and how does this involve multiple characters?” I can’t remember any off the top of my head, but there’s probably some pretty good puzzle designs that we left on the table because it was just like, yep, one player can do this by themselves, and it’s not really taking advantage of the fact that there’s three players—

Chris: Characters.

JP: Three characters, sorry. [laughs] There’s that whole player/character dichotomy. So yeah, it definitely multiplies the complexity of the thing you’re trying to design, because when you’re just trying to make Guybrush Threepwood able to do something funny and interesting, then, that’s one thing, whereas when you’re trying to say, “Oh no, these other two characters need to play a part too…” We got much better at it by the end. We threw out several different areas of the game, threw out several puzzles, and I think by the end we were getting pretty good at just sort of naturally involving the other characters. The areas that we designed last, it was very easy for us to wrap it all together into a thing that multiple characters could do.

Emily: And are these areas at the end of the game? Or did you design it out of order?

JP: They’re kind of all over the place. We didn’t design the game like the first area, then the second area… we jumped around. It’s also going to be variable for players, because depending on which characters you pick in your party, you’re going to be playing through different sections of the game and getting exposed to different puzzles. Like the Hillbilly area that you just played, you get to see into it, but you skirt around it if you don’t have the Hillbilly in your party. So a given player’s path through the game will be variable; it’s not difficult to figure out the entire shape of everything, but you experience content kind of out of order.

Chris: With respect to the multiple characters, I think with a lot of puzzles there’s kind of a sweet spot of two characters having really meaningful cooperation for a puzzle. I think once you get up to requiring three characters to all do things in unison, it gets a little bit insane. But what’s nice is that regardless—there are some puzzles that are more straightforward and only require one character, and there are some that are more involved and require a bit of planning with two, and so on—but what’s nice about playing the game with other people in any of those circumstances is that it’s still an adventure game. So you still have the benefit of two heads banging away on various puzzles, and bouncing ideas back and forth.

That was how I played a lot of games back in the day, especially I remember playing Day of the Tentacle and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis with my good friend Kenny when I was growing up, and we would just play with one of us looking over the other’s shoulder and calling out ideas. So in The Cave, even when not all three characters are necessary at every given moment in the game, there’s still something nice about having a sense of playing an adventure game together and that’s represented on the screen, you’re all jumping around together and trying things, and when someone dies it’s funny—

Emily: Playing it, that was exactly what I was thinking, that I hadn’t had this feeling of collaboration since I was a kid and I used to do that with my friend. That experience of sitting down with someone to play a game, and your heads coming together to do it, is unique. It makes me wonder if playing The Cave as a single player will make it less satisfying?

Chris: I don’t think so personally, because one of the other things I like about The Cave is that it’s very beautiful, it’s a very atmospheric game and I think it’s sort of… there’s the balancing act. On the one hand you have the collaboration and it’s fun, but when you’re playing with one or two other people, you’re probably going to be paying a little less attention to little details in the background, and to the things the cave is narrating, and this and that, and what you gain is the collaboration, and goofiness, and fun. And then when you’re playing it alone, you have to be a little more thoughtful because you have to decide, “I'm going to walk this other character over here, and then I’m going to switch back to the Scientist, and then I’m going to do this,” and I think in the process you’re paying maybe a little more attention to the visual details and to the story that’s going on and to the [details] you find that flesh out these characters’ stories.

So I think it’s a little bit of a different game in each of those scenarios. I don’t know if either is better or worse; that’ll probably just come down to individual players and which of those two sides of the game appeal to them more. There are probably some people who are more into just running around and jumping and having fun with their friends, and there are probably players who might not actually be into that, and they don’t want someone else spoiling their in-depth adventure game experience, and they really want to stay here and look at this vista as long as they want to. Hopefully we support both of those well.

Emily: Chris, as far as the writing goes, what was already done when you came on and what were you brought in to do?

Chris: When I came on to the project, all of the levels had been designed. They hadn’t all been finished, but there was a plan, at the very least, for each level. So we knew what the arc of the game was. And Ron had already determined what these characters were, and what their motivation was. So when I came on, the thing that was left was to actually write all the words in the game. So we kind of split it up… there were some levels where Ron had already started to put out kind of a skeleton of writing, and then there were some that had almost nothing on them.

Emily: Is it mainly the narration from the cave, or are there other talkative characters?

Chris: It depends from level to level. So on the Hillbilly level that you played, that has more non-cave dialogue than most levels do because there are the carnival barkers, that sort of thing. In pretty much every level—not every level, but in most of the levels there are NPC characters that have their own little things, and they range from just quick little barks, to some characters that have their own arc that kind of happens and is pushed along as the player plays through the level. So then they have things that happen to them, for good or for ill (and usually the latter), but the one character who is consistent across the entire game is the cave. So every level has more cave dialogue than anything else. Well, there’s a couple maybe where that isn’t the case.

JP: There are areas that are lighter on cave dialogue, because there’s other stuff happening.

Chris: Yeah, and I would say Hillbilly is actually one of the lightest in cave dialogue, because he would be kind of stepping on the barkers if he was coming in at a moment when the player then runs into a contraption.

JP: That was something that took us a while to get a feel for, how much should the cave talk.

Chris: That was actually one of the things that had not been decided when I came on, and so a lot of our early discussions were figuring out what the identity of the cave is, and how much is he talking, how much is he a constant presence like in Bastion or something, how much does he just set up a level? We kind of ended up somewhere in between. We found that when the cave was talking all the time, like in Bastion, it really started to get overbearing. I think it works great in Bastion—

JP: They committed to it really as a feature; they wrote a lot of code and stuff to pay attention to what the player was doing, and then they wrote to that. We knew that we weren’t going to have time to build that kind of system into the relatively large game that we were building.

Chris: There was that, but there was also the tonal thing that I think we realized after awhile, because we would do read-throughs, where one of us would read the cave while playing the game. We realized when the cave was talking that much, it kind of clashed with an adventure game. The player might be trying to solve a puzzle and not figuring it out—and he’s maybe doing this for ten minutes straight—and the idea of having this character that’s nagging you, or reminding you of things, or talking all the time—it was a little much, because no matter how advanced your tech is in terms of knowing what the player’s doing at any given moment or keeping tabs on what the player’s done, it’s not necessarily going to know what your intention is. So it’s tough to know if the player’s just standing here for a while because he’s stuck, or because he got up to get a snack, or because he’s just doing the thing you do in video games, where you’re just kind of running back and forth and not really doing anything, but you’re just goofing around. And when we were trying to anticipate that stuff too much, it didn’t really work. So we pulled back a bit, and the cave, now, sets up situations and comes in when something really momentous occurs, but for the most part he doesn’t step all over the levels.

Emily: By the end of this game, we won’t just feel like we’ve been through this place and the cave told us what’s going on, right? There’s a story with the cave that’s progressing too?

Chris: Yeah, so at the beginning of the game the story’s kind of set up; the idea is that the cave is this place where people come to find something that they desire very deeply. And over the course of these characters descending into the depths of the cave and finding this item, the cave kind of reveals to them what it is they’re really looking for, that maybe this physical thing they want is really just a stand-in for what they really want. And what are the actual ramifications of this desire that they have, and what are the ramifications of achieving it. So each of these characters has an arc over the game, and it’s told in two forks; there’s the actual, physical, “what’s going on in any given moment” and getting through the character’s level, and they find their thing, and what’s the fallout of that. And then there’s the backstory that you uncover; there’s another mechanic throughout the game that fleshes out more of these characters. So you kind of get their motivation hinted at throughout the game, and then you get the specific thing they want in their character level. With the three different characters, that stuff comes at different intervals throughout the whole game, and then it comes to a head at the end.

Emily: Was it challenging to make a Ron Gilbert-style game with no dialogue? Did you run into challenges where that’s the type of mechanic you would have wanted to use to tell the story, but you couldn’t, because your characters don’t talk?

Chris: I would say it wasn’t a challenge trying to make a “Ron Gilbert” game, because to Ron’s credit, the atmosphere he encouraged on the team wasn’t one that felt like, “We’re making a Ron Gilbert game. This is ‘Ron Gilbert presents Ron Gilbert’s The Cave, a game by Ron Gilbert.’”

JP: He didn’t come in with a big list of design tenets. Maybe he does have that list of design tenets somewhere, but they happen to be my tenets as well? [laughs] My first several months on the project, when we were designing the puzzles and we were thinking about the story, we were constructing the puzzles in terms of things that happen. Like with the Hillbilly, we were saying, “Okay, the Hillbilly’s going to get here and he wants to impress the girl, and he’s going to cheat his way through all of this stuff.”

Emily: So, figuring out what he wants, and then what’s the obstacle?

JP: Exactly, and what character flaws is he going to expose in his pursuit of this thing. So we were thinking about that, and that’s really the point at which most of the story development happened, as we were designing the puzzles. So I think the dialogue was really just like giving a specific voice to that, and putting a fine point on it, you know? And that’s tremendously important; we knew that we were going to need that kind of thing.

Chris: What’s interesting is that there’s really almost no dialogue in the game at all, it’s almost all monologue. Which was hard. That was hard, not in the context of making a Ron Gilbert game, it was just hard hard.

Emily: Hard to keep it interesting?

Chris: It was hard to think of what to do. The personality of the cave changed a lot. Earlier on, he was a lot more sarcastic and kind of mocking. He’s got an edge to him, but earlier on in the development he was a lot more calling out the player—

JP: It was kind of like Mystery Science Theater 3000.

Chris: It made sense. At least, it seemed to us initially to make sense. You’ve got this omniscient character who is not represented on the screen, who is watching all of this transpire, and so this guy knows everything, this guy’s existed for tens of thousands of years. “Well, look at these silly little mortals running around doing things,” of course this guy is going to make fun of them. But it ended up being very dispiriting for the player, and kind of a bummer to write in a lot of cases.

JP: Right, because he was just constantly talking.

Chris: That was the single hardest part, honestly. Finding where the cave should be with that.

JP: Right, because what can somebody say? As a writing exercise, if you have two people sitting next to each other talking, you have a place to start. Whereas a person who’s not soliloquizing, but commenting on something, what are they going to say? To his credit, I think Ron had the idea for where we ended up, of the cave being partly a snarky commentator, but also sort of a wise observer, you know?

Chris: The “storyteller” is what we referred to him as, when we were figuring that out. We bounced a few different archetypes back and forth, and we landed on the one that… it’s more that the cave, he’s seen this, essentially, an infinite number of times before. He’s seen untold numbers of people come down into his cave and think they know what they want in life, and no one does, and so he’s past the point of just taking the piss out of everyone all the time, and more at peace about what goes on when these people come down here. So he’s got a bit of ribbing that he does to these characters, but a lot more of it is this sense of, “Well, let’s see what he gets up to this time.” Kind of a know-it-all uncle, almost.

Emily: Even based on the small demo I saw six months ago, he does seem less snarky and more of an omniscient force.

Chris: We also recast the character, and that came along with the change in direction.

Emily: What do you guys think about the reaction from people who saw the trailer and decided that the game couldn’t possibly be an adventure game?

Chris: I’m going to stick up for those people and say it is completely understandable to me, especially after that first trailer, when someone says, “Well, all I see is side-scrolling and people running around and jumping.” Because it’s hard to convey what makes this game an adventure game in a 30 second clip reel. But I hope, now that people are getting hands-on and are playing it, they’ll see that the bulk of what you’re doing in this game is solving puzzles. Not solving complicated platforming puzzles. There’s running and jumping, but that stuff is a method of conveyance to get you from point to point, the same way that pointing and clicking is in an adventure game. But you wouldn’t say that the soul of an adventure game is clicking on a hotspot to move your character there. Those games consist of a ton of that, but that’s not what the game’s actually about, that’s just the mode of conveyance that allows you to comprehend what the game’s about. I can totally understand why people had those misconceptions and I just hope that as more reporting about the game comes out, and people actually describe what they spent their time doing in the game, hopefully those misconceptions will go away.

JP: The past fifteen years, arguably, have been all about the DNA of adventure games leaking out into other styles of game, and I think that creates a cloud of games around what we consider to be the most essential of the classic adventure games. And I think The Cave is pretty close to those. Another thing about the platforming is that throughout development, any time there was something where you were running around and having to jump or climb something, we consistently said, “This jump is too difficult.” We’re not Super Meat Boy. We want to make this so you jump over the gap, and you make it, and that’s fine. We hope that people won’t have any trouble with it. That was another thing about our testing; we watched a lot of people, and in the course of playing through these puzzles, they were having to traverse the environment a lot. And so in cases where they missed this jump and they died, or it seemed like a lot of trouble grabbing onto this ladder, we did a lot of work on the control scheme. I don’t think our controls are like awesomely tight, perfect feeling Super Meat Boy-type controls, but they look good, and the characters have a lot of personality as they move around, and you really don’t have to worry about dying.

Chris: And if you do, it’s not a big deal.

JP: There is adventure game death. Probably a good half of the things in the game that will kill you are actually much more adventure gamey things that will kill you.

Chris: Right, you flip a switch when the electricity’s not off, and you’re electrocuted. That’s not dying because you messed up a platforming jump, that’s just a funny result of an attempt at a puzzle. And then you’re back in an instant and you can try a different solution.

Emily: I liked it. It’s more to show you that something doesn’t work, and now you know that and have more information to help you solve the puzzle.

Chris: It’s what you’re getting instead of: “I don’t think I can do that.” It’s a different approach to negative feedback. I also think that, even stepping outside The Cave a bit, if you look for example at what Telltale is doing with The Walking Dead, I think what’s happening right now is that we’re seeing different studios and different designers trying different takes on adventure gaming. That game, I think, incorporates a lot of the same classic things that The Cave does, which is “use item A with item-in-the-world B.” A lot of those kinds of core DNA things are similar, but the execution and the look and feel is totally, totally different.

And I think that’s really cool; I think having a multiplicity of design branches off of the notion of an adventure game is more interesting than feeling like we should be arbitrarily tied… you know, what we think of as the canonical point-and-click adventure game, in itself, was only one branch of an adventure game formula that started with text only games, moved to text parser games, moved to graphical adventures with a text parser, then moved to a point-and-click only interface with verbs, and then often moved to a contextual point-and-click interface. I mean, that whole thing evolved even faster than it is now. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, adventure games changed a lot more rapidly than they do now. And then you’ve got guys like Dave Gilbert [of Wadjet Eye Games], who are still working in a slightly more traditional vein, so I think people are sort of spoiled for choice now, which is great. You can find any number of traditional and otherwise games out there. It’s really exciting being part of that whole landscape, instead of just one branch of it.

Emily: Anything else you want to tell Adventure Gamers about The Cave, or what it’s like working with Ron Gilbert?

Chris: He’s not as grumpy as they claim. Don’t let him tell you otherwise.

JP: Really, it’s all an act.