A Sierra Retrospective: Part 4 - Works of Art page 2

A Sierra Retrospective

A lookback at legendary game companies or series

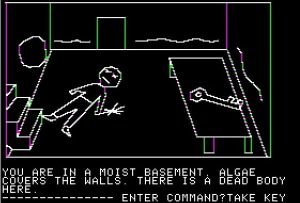

From the earliest days of Mystery House’s black and white stick figures and line drawings to full-colour 3D presentations, Sierra always tried to stay at the forefront of graphics technology, innovating as they went.

In their early 16 colour games, the artwork would be drawn either by hand, then plotted into the computer using coordinates as if drawn on a piece of grid paper, or it would be drawn directly into the computer using a tablet device. These vector-based graphics were all coded within the game, a line would be drawn between two sets of coordinates, and a colour would fill the spaces between lines. It wasn’t an easy process but it worked well and saved a lot of disk space, which was always at a premium.

For Sierra, one of the biggest challenges in graphics came in the early 1990s when 256 colour VGA graphics cards reached the PC market.

|

The industry has come a long way since the humble beginnings of the first graphic adventure, Sierra's Mystery House |

“Once VGA came in, we actually took a little different turn than most of the studios working at the time and realised that because you only had 256 colours, if you worked in a digital paint program like Deluxe Paint, everything looked very pixelated. It was very difficult to make anything look smooth or to imply colours,” says Bill Davis, Sierra’s first Creative Director.

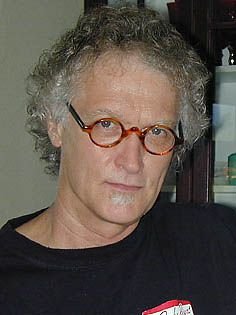

Hiring Bill was a major coup for Sierra, bringing his highly-acclaimed talents and extensive experience as an artist, graphic designer and painter into the fold.

“When I came up there, they had a handful of artists, about five artists I think; most of them there were self-trained. I realised they had no production system; no one in the business did,” Bill claims. “In other words, they would just put some artists together with some programmers and they would start making a game. In many cases they would design as they went along, they would try different things and go from there. The first thing I realised we needed to do, because we were looking at really growing the company, was I had to hire a lot of people for what we wanted to do because we knew VGA was coming down the pipe and my plans for that were a lot different from what we’d been doing.”

It was at this point that Bill decided they could draw backgrounds and animations with traditional media and then scan that work into the game, giving a much more realistic and less pixelated look than their competitors.

“We started painting with traditional media and then had our programming team develop some amazing codecs to scan the artwork in. That also allowed us to key scenes for other people and send them overseas to places like Korea and have them paint them. So we could really up the production because we [alone] never would have been able to raise the quality of production that we wanted.”

A clear indication that the changes made to the design process for 256 colour games was successful was the recognition Sierra received from their competitors, as Bill Davis recalls.

|

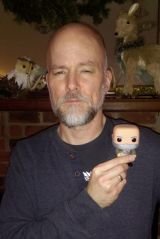

Sierra’s first Creative Director, Bill Davis

|

“When we came out with King’s Quest V, the first VGA version of the game, we heard through the pipeline that LucasArts was furious, saying they’ll never be able to sustain that, they’re going to go bankrupt trying to build games of that kind of quality. So we were doing what we wanted to do, we were hitting nerves with the other companies and trying to surprise them. It was pretty competitive so you had to do that.”

Something else Bill looked at changing was the ever-evolving art styles of the games. He wanted to bring a consistent look to the games, so each series, while distinctive in itself, would have a unified approach, as Josh Mandel, Designer and Writer for Sierra, explains. “[Bill] had previously worked at NBC and had an Emmy and he was high up there. And he felt that Sierra games should have a definite graphic flavour through the series. He looked at King’s Quest and every King’s Quest looks different, and every Space Quest looks different. He really wanted to unify that and stop the chaos.”

“I’m a big believer, especially when you’re doing art styles, in suiting the style to the genre,” Bill says. “There was a lot of thinking in the beginning, especially with the newer games and resurfacing the older games, [about] kind of picking what style is really going to be the optimum style and have the most wow factor for these games when they come out. I don’t think they were doing that in the industry, they were just doing art.

“So I would do things, like, with Leisure Suit Larry, why don’t we do cubism? We could do it, it would be great and it would suit the kind of wacky world that Larry lived in. When we started doing the edutainment titles, games like Twisty History [working title for Pepper’s Adventures in Time], we had a game that was going back in time to be with Ben Franklin. I thought about Grant Wood, a great American artist who painted a lot of revolutionary scenes in America, so we styled it that way. So it was that kind of stuff.

|

|

Instead of ever-changing art styles within series, Bill Davis encouraged a more consistent internal approach. Leisure Suit Larry was given a fuller, more cartoony style to better suit its comic sensibilities when the 256 colour remake was released.

“I really get bored with – and I’d get bored with today if I was still at Sierra – this kind of game realism that goes on now that everybody copies. It’s in most of the shooters. Each game does it a little better but they all look the same. You don’t have to do that; they can all look completely different, so that’s what I always seek out,” Bill says. “That’s what I’d be trying to do at a company like Sierra – trying to apply the best look for each game.”

Another change Bill made was to introduce the role of Art Director to the process, giving one person oversight of the art for a game, something that was now required as the number of artists had grown enormously since their earlier games.

The Art Director’s job was very extensive and required a lot of preparation, as Marc Hudgins, who held that role on Quest for Glory IV, describes. “You’re basically given the design document, whatever shape it was in at the time the project was spun up. It was usually a list of what we used to call rooms – you know, screens – and a rough outline of the progression through the game.”

Marc goes on, saying: “Part of it is like, well, what are the environments here? What needs to be designed? What’s the tone of this? What’s the visual approach to take to this? What characters need to be designed? And then breaking out animation lists. I’d started out as an animator so that was always a big thing for me, a very animation-focussed approach. I think it was different because a lot of the previous Lead Artists were more illustrators who did the backgrounds. As an animator, my concern was making sure the backgrounds supported the animation and not the other way around. So I would try to compile as much as I could about every scene. What the animation needs were and stage that. And sketch out background designs that would accommodate the action that needed to be supported.”

Rotoscoping was a process that Bill Davis had introduced to Sierra at the start of the VGA era as, with only 256 colours, using any shortcuts would be more noticeable. “The animation was pretty crude and I realised once again with 256 colours it could look better but we needed to animate better so I started hiring real animators – we didn’t have any – to do squash and stretch.”

|

VGA games like KQ5 used two types of animation: rotoscoping and "squash and stretch" |

Bill elaborates on the differences in the two animation styles: “You’ve got two different kinds of animation, even in features. You’ve got the way Snow White moves in Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, and you’ve got the way the Dwarves move. So Snow White is rotoscoped, but the dwarves are done with what they call squash and stretch animation. So they’re very exaggerated. The reason they call it squash and stretch is when their weight comes down on a step they squash down like a rubber ball, and when they jump up they’re very elastic and they stretch so it gives a varied look to the way a character moves. They’re much more bouncy and animated and the rotoscoping is much more subtle.”

“What I wanted to do, I wanted our characters like King Graham to be rotoscoped so he moved in a very real way, but then I wanted any dwarves or trolls or other characters in the game to be squash and stretch.”

Creating a setup for rotoscoping was left in the hands of Dan Foy, a programmer at Sierra who came up with a unique way of dealing with the issue.

“I needed to find a way we could rotoscope walkers,” Bill recalls, “So we set up a very dangerous treadmill without rails on it and [Dan] set up a system that could capture it. We’d take it into the tools and touch it up a little bit and that’s how we rotoscoped. It sped up animation, I tell you. Now it’s motion capture, but same kind of principle.”

Marc Hudgins also worked as the Animation Director on King’s Quest VII, a game that saw an increase in graphic resolution, something that brought greater clarity for the player but also caused more problems for the production team.

|

Marc Hudgins, Animation Director on King's Quest VII |

“King’s Quest VII was our first 640x480, which was a bit of a problem,” Marc says. “I was actually concerned about that because we were getting to a point where there was enough resolution where the warts would begin to show. You couldn’t cover them up; you’re still making weird choices about what you could do to clean up a drawing. It wasn’t high enough resolution for you to do really clean animation, and it wasn’t low enough you could kind of make it fudged.”

The game turned out to be a massive job for Marc, taking on art responsibilities after the Art Director moved to the Seattle studio.

“That was a rough one. It was probably the most ambitious hand-animated thing we’d attempted there. Roberta’s idea for this thing, this was going to be full blown hand-animation like a Disney film. It was a big game. When I looked at the scope of it, and I looked at the time we had to get this thing done… I came on board in February, maybe January at the earliest, and it was going to ship by Thanksgiving. Less than a year to make the most ambitious game we’d ever tried in terms of hand-drawn animation stuff.”

Marc says his most enjoyable part of working on King’s Quest VII was in populating the game: “I designed all the characters. Between 80 and 100. That was fun; I love character design.”

Another issue Sierra encountered due to the increase in quality was that animations required more frames than had previously been needed, so a lot more work was required of the artists.

“We didn’t have enough in-house staff to do the animation so we had to contract with some outsourced type of thing. The first thing we did was we got this company in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and they said, yes, we can take it on. So we went over to Saint Petersburg and set them up with our tools and explained the process to them. We started getting stuff back but after less than a month they said, ‘you know what, we can’t do all of this’,” Marc says.

Taking some of the work away from the Russian studio, Sierra contracted the animation work to three other studios, which caused other problems.

|

Animations for KQ7 were outsourced overseas to help with the hugely ambitious demand |

“We had a studio in Croatia, we had a studio in upstate New York, and we had a studio in South Carolina,” Marc remembers. “We had no time for revisions, so my job was to try and make sure that it looked, as best I could, like it was all drawn by one person. Which I don’t think I really succeeded at. Some were really tight, some were a lot looser than others. It was a real challenge. That was the first time I had really encountered that level of management in my life. I spent my life on fax machines because we didn’t have the internet yet, not in any meaningful way. I would fax drawings off to these studios and I would make phone calls at weird hours because I’d be calling Saint Petersburg, Russia. It was nuts.”

“Everything would come into the studio raw from these places and we basically took people off every single project and had people cleaning up the animation for the game. So I probably had about 30 people in the studio actually working on it. Just taking this raw stuff in and cleaning it up and making it appropriate to use in the game. There were no retakes. Everything went in, we fixed what we could. I think those studios did the best they could but we were all under enormous pressure to get that thing out on time,” Marc says.

As was the usual situation with game production at Sierra, there was a lot of stress and a lot of challenging issues to overcome, but in the end the game that was released went on to become one of Sierra’s biggest hits that year.

A legacy is something that is handed down from one generation to the next, and Sierra has certainly left an enduring impression on the industry and the many gamers who grew up with it. As a groundbreaking genre pioneer, the company’s influence is still keenly felt in the many adventure games today, a lasting heritage that everyone who worked there can be proud of. In our final article in this Sierra retrospective, we look at that legacy and the people that created it, as well as those who continue to be inspired by it today.