Book reviews: The Sierra Adventure and Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings

Sierra On-Line is the company most responsible for the point-and-click graphic adventure genre that we all love. That’s not a controversial statement. It may not be the company that produced your favorite adventure games, but it was a pioneer in so many ways, taking the text adventure format and revolutionizing it by putting a pretty visual sheen on it—and then continuing to iterate year after year, improving its technology, making that sheen even prettier while continuing to hone its storytelling. Sierra made celebrities of its designers, turned a small California town into the economically booming home of a publicly traded company, paved the way for online gaming with a visionary service far ahead of its time, and cultivated a fanbase of genre enthusiasts that has allowed for a site like Adventure Gamers to thrive for more than two decades.

Behind the scenes, however, largely buried within its headquarters, were years and years of untold or half-told stories, leading to plenty of gossip and rumors of conflicts that underscored the memories of the great games that we cherished. Sierra’s designers have remained relatively quiet over the years, almost always preferring not to dwell on the past or to avoid interviews entirely. As we got farther and farther away from that era, it was reasonable to fear that those untold details would be forever lost to time.

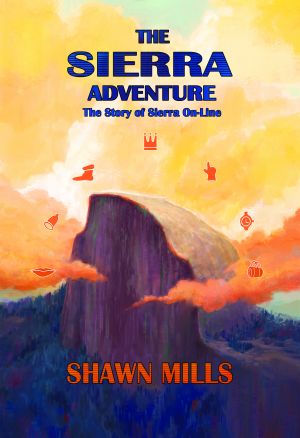

Enter Shawn Mills, co-founder of indie adventure developer Infamous Quests (who cut their teeth in the genre developing outstanding VGA remakes of Sierra adventures Space Quest II and King’s Quest III as Infamous Adventures), who went looking for a deep history of Sierra and, finding none, asked the question, “If I can’t find a book, why not write it myself?” Armed with a journalism degree and a deep personal affection for the company that helped inspire his own games, Shawn spent a number of years tracking down a myriad of producers, designers, and various other former employees who could tell the story, and after a successful Kickstarter campaign, has now released The Sierra Adventure: The Story of Sierra On-Line.

Though the contributions of other Sierra notables are extensive, it’s interesting to note the very limited participation of founder and long-time CEO Ken Williams, who has for years appeared to have absolutely no interest in reliving his two decades with the company he created, instead establishing a second successful career as a boating enthusiast (with three published books on the subject) and world traveler with his wife, equally famous King’s Quest designer Roberta Williams. Though he was briefly interviewed by Shawn, it’s perhaps not surprising that Ken would not want to participate extensively in the re-telling of a story that ended quite tragically as a direct result of many of his decisions. In fact, Sierra stalwart Josh Mandel states in the foreword to The Sierra Adventure: “A book from [Ken or Roberta Williams] would, you would think, be the most comprehensive and revealing.”

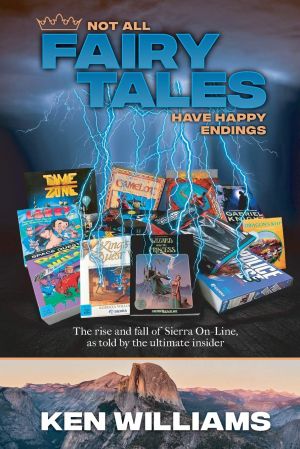

If 2020 had been what we’d all think of as “normal,” Ken and Roberta would likely have been somewhere on the open seas, continuing to enjoy their retirement from the games industry and thinking as little about the Sierra legacy as possible. But 2020 has been far from normal, and the COVID virus led to the cancellation of the boating season—and so Ken, quarantined in Seattle with nothing to do, faced the suggestion from his wife: “Maybe you could write a book.” With Ken never needing much prompting to create something new, the domain kensbook.com came alive and just a few short months later, the self-published Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings has brought us what Sierra devotees have always craved: the “ultimate insider” account of the actual company behind the legend.

The Sierra Adventure is written similarly to an oral history format, with strong primary reliance on numerous interviews conducted, both with the designers who need no introduction as well as many other names you probably remember from watching the opening credit sequences: creative director Bill Davis, producer Guruka Singh Khalsa, system developer Mark Hood, composer Mark Seibert, and so many more. It does not have any art or photos; it is simply a briskly paced 300-page historical document that allows the interview subjects to tell their story, for better or worse.

The Sierra Adventure is written similarly to an oral history format, with strong primary reliance on numerous interviews conducted, both with the designers who need no introduction as well as many other names you probably remember from watching the opening credit sequences: creative director Bill Davis, producer Guruka Singh Khalsa, system developer Mark Hood, composer Mark Seibert, and so many more. It does not have any art or photos; it is simply a briskly paced 300-page historical document that allows the interview subjects to tell their story, for better or worse.

Not much time is spent in the pre-1984 days; instead the story is primarily focused on Sierra as an adventure game developer. The chapters are well-structured chronologically, moving through each era studiously and discussing almost every major adventure release for at least 1-2 pages, while also carefully telling the story of the innovations in engine, graphics, sound and other essential design areas. The interviews bring the reader into the internal workings of Oakhurst in a remarkable way: designers talk about how cubicle layouts affected communication internally, and producers can still remember quite clearly why 1990’s Codename: ICEMAN was Sierra’s first real disastrous failure. To his credit, Shawn avoids adding too much of his own personal editorializing. He also goes out of his way to apologize at the beginning for not being able to adequately discuss every Sierra game and subsidiary product, a fair concern given the breadth of the developer’s catalog.

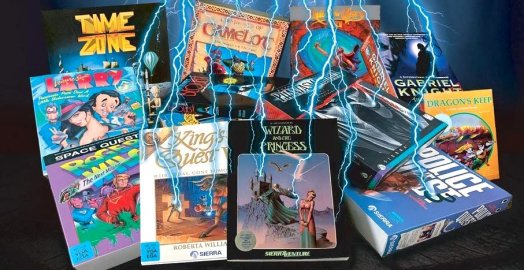

Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings is a definite contrast. Though its foreboding title sets the stage for a very negative tale, actually Ken’s book is paced with an almost frenetic upbeat energy. Relying on no interviews and seemingly little professional editing (though Al Lowe is one of three individuals thanked for their “editing skills” and the book is mostly free of grammar and format issues), it is much less a chronological history and more a whirlwind of recollections that could only come from the founder of the company. It is also heavily illustrated, with lots of old photos, historical documents such as an authentic Sierra stock certificate and a typed letter to Ken from Steve Wozniak, and Sierra box art and screenshots.

Ken’s account of the 1982 “board meeting from hell,” which has never been reported before, is frightening and hilarious in its depiction of how the company’s informal startup style clashed heavily with the suited millionaires providing Sierra their first shot of venture capital. Another significant highlight is the chapter that explains in detail how King’s Quest was made in “3D,” complete with visual representation of the process of splitting the game backgrounds into 14 different horizontal planes, which is eye-poppingly awesome for any game historian. Less awesome are digressions like the bizarre non sequitur story where Ken veers abruptly from a discussion of Leisure Suit Larry into a half-page story about the red Porsche he always wanted—complete with a photo. Though these detours are sometimes maddening, they are never boring, and it’s hard to not find his energy endearing all these decades later. Ken is also entirely sincere and clear-headed about controversial topics like the hiring of Daryl Gates, Sierra’s journey into adult-focused games, and the ill-fated merger with Broderbund, wherein he notes: “I believe I am the one who screwed up the deal.”

Both books utilize sub-chapters to tell additional stories to the main themes. The Sierra Adventure has a relatively small number of these interludes, and they are used to cover less important but interesting topics such as the Hoyle card games, Sierra’s foray into edutainment, and the strange story of Al Lowe’s cancelled Capitol Punishment, a political satire platform game featuring caricatures of Bill and Hillary Clinton whitewater rafting that probably would have aged about as badly as it sounds.

The interludes in Not All Fairy Tales, though referred to as such (indeed, labeled by Ken as “a brief pause in the story, so I can wedge something in”), are numbered chapters and are exactly what they say: an abrupt break so Ken can divert to a new topic, usually at great length, that he seemingly thought of in the middle of writing. There is a 13-page interlude on “How to Be a Software Engineer,” a 17-page examination of “Managing Growth,” and a massive section only one-third into the book called “Short Takes,” which is literally 25 pages of “a few short and random memories that didn’t seem to fit elsewhere.” One of those is nothing more than: “Hey, look at this cool 1981 photo!” There are also shorter segments on licensed property, working with family, and many others, and at final count the interludes compose more than 25% of the book’s 376 pages. I would imagine such a structure would drive professional editors crazy, but it is all consistent with the charmingly spastic energy that is the book’s defining tone.

The interludes in Not All Fairy Tales, though referred to as such (indeed, labeled by Ken as “a brief pause in the story, so I can wedge something in”), are numbered chapters and are exactly what they say: an abrupt break so Ken can divert to a new topic, usually at great length, that he seemingly thought of in the middle of writing. There is a 13-page interlude on “How to Be a Software Engineer,” a 17-page examination of “Managing Growth,” and a massive section only one-third into the book called “Short Takes,” which is literally 25 pages of “a few short and random memories that didn’t seem to fit elsewhere.” One of those is nothing more than: “Hey, look at this cool 1981 photo!” There are also shorter segments on licensed property, working with family, and many others, and at final count the interludes compose more than 25% of the book’s 376 pages. I would imagine such a structure would drive professional editors crazy, but it is all consistent with the charmingly spastic energy that is the book’s defining tone.

If you were to sketch the coverage of events in these books across a timeline of Sierra’s chronology, you’d be surprised to see two fairly non-intersecting lines. Although some famous controversies like the hiring of Daryl Gates and game achievements such as the groundbreaking multiplayer RPG The Realm Online are at least mentioned in each, there are really only three events covered extensively in both: how the development (and rapid failure) of the IBM PCjr allowed for the creation of King’s Quest, the game that saved Sierra from early bankruptcy and created the graphic adventure genre; fourteen years later, the painfully troubled development of King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity (a tragedy that quite honestly will make the game difficult for me to play again); and the development, sale, and ultimate failure of The Sierra Network, the first online gaming network that was later rebranded as ImagiNation, but for reasons that seem so obvious now was much too far ahead of its time and not financially sustainable. I was a subscriber of INN for nearly a year as a teenager, and reading these sections was the high point of nostalgia overload for me, although Ken’s remarkably extensive chapter on the subject opens by referring to it as “the biggest sadness of them all.”

Other than these crucial topics, the books occupy almost entirely separate timelines, with Not All Fairy Tales going deep into the company’s business aspects and closely following the excruciating pain of the CUC sale, the subsequent accounting fraud, and Ken’s departure from the company in 1998, while The Sierra Adventure stays much more focused on the games and the slow, one-by-one failure of each of the flagship adventure series as the Oakhurst studio slowly descended into its eventual closing in 1999. I read Shawn’s book first and I noted as I finished that it was rather light on Ken’s role in the company and the merger/management dramas in the mid to late ’90s, but Ken’s book fills in every detail on those matters, even to the extent of his reprinting a November 1996 ultimatum email sent to his new CUC executives.

Although these and many other anecdotes are told in expansive detail, you cannot expect the entire encyclopedia about Sierra to be written in less than 700 total pages. If you remember being a fan of the company and their products, you surely have specific memories or questions that you would like more of an answer to. I personally was always fascinated by the strange circumstances that Police Quest designer Jim Walls left under, but his departure is barely mentioned by Shawn and not at all by Ken, and neither book explores the controversial story of Tsunami Media (another Oakhurst game company that splintered from Sierra and raided Walls, among others, in the early 1990s)—in fact, Ken doesn’t even mention them by name. You’re sure to feel a certain topic or game is under-discussed, but such omissions are understandable and minor, and what is present in both books is great history and delightful nostalgia.

There’s not a lot of mystery as to my feelings about Sierra On-Line. Over 40 of their original game boxes, full of floppy disks and vintage manuals, are neatly organized on a shelf next to me as I type this. It was a deep passion for their adventures that fed my love of all electronic gaming, and led me to pursue a hobby in adventure game journalism almost 22 years ago. So if your question is, do we really need two books on one company, my answer is clear: just hook as much Sierra-related content as possible directly into my veins. I’m ready to read ten more—even with as much as these two accounts share, there are surely more detailed stories to be told.

What’s really remarkable about these two specific books, though, is how perfectly they complement each other. Shawn Mills takes a studious, chronological approach with rigorous detail and an abundance of perspectives, hitting all kinds of nostalgia sweet spots during the journey. He never gets bogged down, but keeps the pace quick and consistent as he moves through the company’s history. And while the celebrity designers have certainly been written about and interviewed over the years, The Sierra Adventure also puts a welcome focus on the producers and the details of the development side of game design that has never been adequately covered. Ken Williams digs only into his own memories, sometimes of more than four decades ago, and delivers nothing but honest, sobering reflection and plenty of delightful inside information, almost none of which has been written about—in fact, Ken admits that his research for the book uncovered information even he didn’t previously know. He reminisces with considerable and sincere regret, but still hasn’t lost his seemingly boundless energy to talk about his company, which is distracting at times but also infectious.

The two books couldn’t be more divergent in their approach, and they end up miraculously coordinated in their content, with only a few prominent events earning considerable discussion in each and barely any other overlap to speak of. Even if you weren’t alive when Sierra released its final internally developed adventure in November 1999, if you love this genre and gaming history in general, these two books together provide a broad and fascinating perspective inside what still may be the most important computer game company ever. They are both, in different ways, a wonderful separate read, and though not intentional, together they provide one of the best surprises that 2020 has brought us.

Disclaimer: Shawn Mills is a volunteer writer for Adventure Gamers, and The Sierra Adventure was edited by fellow staff members Jack Allin and Emily Morganti. This article solely represents the opinion of its author.