Sam Barlow (Her Story, Telling Lies) – Part 2 interview

In the first installment of our two-part interview, Sam Barlow and I discussed his upcoming adventure Telling Lies and the concept of "exploring" video. In the second half of our lengthy Skype conversation, we looked back at the genesis and evolution of this unique method of storytelling, Sam's involvement in the choice-driven WarGames, and the future of interactive movies.

Ingmar Böke: One thing I noticed about Her Story was that it has a very plausible explanation for avoiding being confronted with another character where you could directly ask questions in a live situation, and it seems the same goes for Telling Lies. Are certain limitations crucial for making games like Her Story and Telling Lies work?

Sam Barlow: Certainly, when I made Her Story, a lot of these things I was doing naively or on instinct. But in retrospect, my big passion in games when I was a kid was text adventures. I loved the magic of the text parser; the idea at least that you could type anything and it will happen. And every now and again, there would be a text game where that was true. But in general, you knew that there were a set of ten or twenty verbs that would get you through most games. And if I am playing a text game and I say something and the game doesn’t understand it and I get a stupid answer, instantly it’s a buzzkill. Whereas in Her Story, I understood it is a constraint that if I search for a word and it wasn’t said, it’s not there. Some of the best responses I had to Her Story were people saying that despite the artifice of the whole thing, despite the fact that it was about being sat in front of the computer, once they were immersed in it, they had the feeling of having a conversation with Viva’s character in a way that felt more organic and immersive than the act of talking to a simulated NPC in another video game. So I think it was by not having to worry about some of that suspension of disbelief and supporting some of those things, I think it definitely frees you up.

|

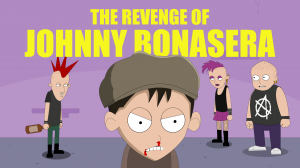

Viva Seifert's impressive multi-layered performance was crucial in creating a player connection to Her Story's Hannah Smith |

I was really interested when people said that they had this real sense of a connection, of intimacy, of some kind of interpersonal dialogue with Viva’s character in Her Story, so with Telling Lies I really wanted to dig into that. Like, how is that unique? One of the things I thought a bit about was, if you’re watching a movie and there is a scene in a bedroom between two characters talking – you know, some pillow talk or having some dramatic discussion – either it’s shot "invisibly" where you are not aware of the camera because it’s using the conventions of cinema and you’re essentially the invisible observer and there is no sense that you are eavesdropping, so it’s fine that you’re present in the scene. Or there is a David Lynch-type movie and it’s been shot through the slats of a cupboard; you can play up the presence of the camera and a sense of voyeurism and the sense that you are listening in to a conversation you shouldn’t be. I think this game creates an interesting middle ground where you have some presence in the scene – the interactivity gives you some personal connection to it – but really the nearest analogy to what I was trying to do here is novels.

What is unique about novels is that you are inside the mind of a character. You can be present in their thought processes, you’re seeing everything through their eyes, and in most novels that doesn’t feel at all icky or voyeuristic. You just get a sense of this intense insight about the character by seeing the world from their perspective. And Telling Lies’ format gives you some of that because the amount of work your imagination is doing to fill in the blanks, to infer what’s happening on the other side of the conversation, the freedom you have to move around in these scenes, really does compel you to inhabit these characters using your imagination in a way that reminds me somewhat of the novelistic feel. At the same time, you have the advantages of filmed performance – you see these characters, you can infer what is going on and you can have that emotional reaction to the scene and the acting and stuff.

It’s definitely 100% something that emerges from the constructs, that I think was a learning process for me. It was something I believed I was proving with Her Story, that so often in video games the conventional logic now is that nothing needs to be left to the imagination. A video game is different from film in that I can see 360 degrees around the location – if I want to walk over to the fridge and open it, I can do that. If I’m playing Grand Theft Auto and a character goes from one side of the town to another, I can sit in the car and drive, stop at every light and see every street corner. And so there is this idea that video games can unpack and unspool and give you everything. The idea of avoiding cutscenes to some extent is that everything will happen in real time; you will see everything unfold, and the pacing is a different thing. There’s also a challenge in a video game that so often the story is also your mission objective and is also your tutorial and is your guidepost telling you what to do next. It was found that in making a conventional video game, it was important that everything was explained. If your character needs to go over this hill to kill a dragon, then it needs to be really obvious. Some other character is going to say “you need to go over the hill and kill a dragon,” whereas good storytelling oftentimes would have characters talking about their breakfast and the subtext is that he is going to kill the dragon.

What I found when I was preparing Her Story was, particularly in an interactive story where you already have the player’s brain and imagination engaged in your story, I think actually showing less, creating deliberate gaps for their imagination to fill, is super-powerful. Some of the earlier video games had levels of abstraction that were necessary, not in real time but because graphics couldn’t actually show you everything. Those were subtle ways in which we were encouraging imagination. I think accidentally with Her Story, and knowingly with Telling Lies, it is very much about deliberately telling a story through some of the negative space. Telling a story in which you are always only seeing a portion of what was happening.

Again, this is anti-cinematic; the story is very dramatic, but if they were shooting a Hollywood movie of this, they would be filming entirely different scenes. Here we are only seeing our characters when they talk to each other online, in this building captured by the government. So if something big happens in a character’s life, there’s no reason that they’d be filming it, so we don’t see it. If two characters are together in the same room, they are probably not Skyping each other so we probably don’t see those moments. So a lot of times the big plot events in the story are not happening on-screen, in the way that in a Shakespearean play King Henry would run in from the battle and would be like, “oh my God that battle was awful, I saw a hundred men killed!” You are imagining this incredible battle, and you only see the before and after, and we are very much in that world. And that is such a lovely constraint because it gives you the moments that are more personal and more intimate, and it allows you to imagine these bigger events and add that colour to everything. That exercises the muscle of your imagination, which is already engaged because you’re in this interactive world and you are making choices, you’re paying attention, you’re listening to what people are saying, you’re taking notes of words and phrases, you’re inferring from this other clip you saw, “Oh! Now understand what was happening; I understand who this other person is.”

I think it’s very powerful to encourage people, by necessity, to use their imaginations. If I am sat in the cinema or I’m on my sofa reading a book, 10% of my body is engaged with flipping the pages and stopping the book from falling out of my hands, 5% is engaged with eating popcorn, but the vast majority of my mental processes are engaged in watching the story on the screen and suspending my disbelief and empathising with characters and imagining what’s going to happen next. We’re putting the full force of our imagination and all of our weird human programming into making this story come to life. But if you go over to... let’s say a military shooter, now I’m holding this device with two sticks and a bunch of buttons or a mouse and a keyboard, and I’m now looking at a two-dimensional representation of a 3D battlefield, and I’m choosing where to point my crosshairs and I’m tracking moving targets and I’m shooting them, I’m worrying about my ammo count, I’m deciding whether to switch to this other weapon, and I’m thinking about my larger objective, how I will have to get from A to B to C. I’m managing all of this stuff, and at the same time there’s a story going on. So the amount of my brain that I have left over to care about characters, to do all the stuff I would be doing in other story mediums is much smaller. So some video games will alternate. They will give me all the adrenaline of an incredible fast-paced action scene, and then there would be a cut scene in which the story moments happen. That’s Uncharted, essentially. Uncharted would slow things down and allow me to walk through a marketplace so I can engage in conversation.

|

Her Story is a part text-adventure, part FMV mystery based on keywords recognized by the video database |

The beautiful sweet spot that I accidentally discovered with Her Story was by making the game mechanic be literally the story itself. You had a much tighter synthesis here, because I’m watching a scene and I’m suspending disbelief and I’m being moved by the characters and I’m empathising with them and I’m thinking about plot, and I’m thinking about what happened here, what is going to happen, what didn’t happen. I’m doing all that and I’m listening to the words they are speaking and inferring the subtext from what they’re saying, and that is all inextricably linked to the story and gameplay. Because picking up on that character name or that turn of phrase is how I navigate to the next clip. Putting the pieces of the story together is mastery over this world of video.

So it’s super-fun because you get some of that deep immersive connection that you have to a video game through its mechanics, but it’s embedded and enmeshed directly in the story. The best bits of a traditional adventure game would achieve that. Sometimes there are great puzzles or great sequences in classic adventure games which pull that off where you’re in the world and the mechanics are to do with the plot and the story and the characters, and it feels fantastic. And then you get stuck with the busy work, and then the mechanics and the story will separate, like oil and water. But yes, very much there is this sweet spot I’ve discovered that reiterates constraints, enables us to combine story and mechanics in a way that is never frustrating.

It wasn’t widely held but the occasions where people would ask if Her Story is really a game, I was never too bothered about because I knew how complicated and interactive a thing it was, how much involvement your brain has with it. So for me whether you call it a game or not, I always felt like it was sufficiently rich and interesting as a piece of interactive entertainment. Take something like Uncharted, which is completely valid but every player is experiencing the same sequence in the same way. Everything in that game is geared towards making you press the button when they want you to, so it all works quite beautifully. Screw up or try to do something that it is not anticipating, it pulls apart, and so really, as much as that is an interactive piece of adventure and storytelling, it’s not giving you, the user, a heck of a lot of agency or respect. Whereas something like Her Story is genuinely going to let you move around, go in directions that you want, and you are free to do that. But every time you’re watching a clip, you’re thinking on several levels, you’re listening and paying attention. It is not the bad idea of an interactive movie where you press a button and sit back. You’re pressing it and leaning in and thinking about it. The idea of this enhanced scrubbing mechanic, the idea of dropping you into different parts of the clips, was to keep you connected and to keep a finger on the mouse or a touch screen as you’re playing this. It really is a very interactive experience.

Continued on the next page...