Review for The White Door

Those who have spent any time with the Rusty Lake series of indie games will know them as absurdist stints in a world walking the line between grotesquery and black humor. While The White Door features some similar design elements, such as a stylistically simple art style and uncomplicated gameplay, this game is a wholly different experience than its predecessors in terms of tone, dropping the cheeky black humor and making a more concerted effort to explore the inner struggle of someone battling with feelings of loss and depression in an easily digestible bite-size package. While it succeeds at being thought-provoking at times, it is so determined to avoid mainstream sensibilities that it can be a tad off-putting as a result.

The White Door is named after the mental health facility Robert Hill spends the majority of the game in. Robert finds himself confined to a solitary room, having to follow the same routine day in and day out, while doctors and nurses set tasks for him to complete and challenges for him to solve. Their hope is that he’ll regain his memory, which returns to him bit by bit in his nightly dreams, letting us discover why he’s in this institution in the first place. As such, the game’s title also represents his ultimate goal – the white door of his room that he seeks to walk through to regain his freedom.

Robert’s dreams allow you to piece together his backstory, informing his current mental state and gradually revealing the whole picture of his character – or at least make an attempt to do so. The first few nights portray simple-to-understand events: Robert’s girlfriend breaks up with him, his work performance suffers, and he’s let go from his job – things that are easy to relate to. From there on his dreams become darker and more cryptic, though. Events take a grim turn for the worse, causing his loosening grip on reality to spiral further out of control.

As the game’s seven-day timeframe ticks by, Robert’s dreams continue to grow more unhinged and his troubled memories begin to spill into his daily routine. For example, he sees the tiny silhouette of a man, a vision from his dreams, running across his table and climbing around his room even during the day while he’s wide awake. All this creates a surreal atmosphere that’s certainly interesting to guess along with, though it doesn’t provide any clear-cut answers in terms of narrative.

Since the dreams are the closest thing The White Door has to plot development, they need to get certain story beats across and therefore limit player agency to the point where your only job is to perform whatever on-screen actions are being described. For example, if the heavily-accented narrator (one of a handful of voice actors present during dream sequences) mentions that Robert’s girlfriend pulled her chair up to the table in the diner where they break up, you’ll need to click to nudge the chair closer. When Robert purchases a gun, it’s your job to slide the appropriate bills and coins across the counter equal to the price revealed by the narration. Simple click-and-drag actions like this make up the lion’s share of this half of the gameplay, though occasionally something slightly more involved occurs, like directing Robert’s car across a map of city streets during a bird’s-eye-view sequence.

In contrast to these simplistic gameplay elements that push the plot along, the daytime segments feature The White Door’s bona fide puzzle elements, embedded in Robert’s daily room routine for much of the game’s 2-3 hour length. The protagonist’s day begins with getting out of bed, after which the events posted on his room’s itinerary, like breakfast at 8:00 and recreation at 20:00, must be followed in order, with the clock on the wall only advancing once an activity has been completed. The objective here seems to be to drive home the mundane nature of Robert’s existence, as brushing teeth and using the toilet can hardly be considered pulse-pounding adventure activities, but the daily schedule does provide for a couple of built-in puzzle moments.

The staff member who comes for each day’s 11:00 patient check-up will ask Robert several questions, to which you must spell out the correct responses using an on-screen letter bank. This tests how observant you are, as the answers can be found on documents and items scattered around the room. It’s vanilla stuff, like a certain date or the ingredients of a packet of bird food, but it forces you to pay attention to the minutiae of the narrative. (You can always leave the attendant waiting at the door to double-check an answer.) The 15:00 memory training is similarly a puzzle opportunity, requiring you to interact with a desktop computer to solve a different mini-puzzle each day. There are really only a couple of chances to interrupt Robert’s routine: a shuttered window provides a glimpse of an outdoor garden, with slight differences each day; and a mysterious locked cabinet begs to be – and eventually can be – opened.

Despite Robert’s day-to-day life sounding quite repetitive, the developers have managed to make each day into a novel experience, even if the framework generally follows the same schedule-based outline. And it’s all underscored by an unobtrusive soundtrack of haunting synthesizers during the day and more emotional piano pieces accentuating his dreamscapes, at times dropping away to silence entirely. About the time his mental state begins to noticeably deteriorate, Robert even spends an involuntary stretch in a padded cell, which comes complete with its own unique puzzles involving uncovering several code words that open a wall panel. This is a game built around the monotony of institutionalized life, but boredom is one thing that rarely rears its head.

One feeling that is emphasized here, though, is a sense of weird unease. Playing and later reflecting on what I’d seen, to me, was akin to recalling an extremely off-putting dream, with the game routinely providing bizarre moments that made me feel unnerved, like returning to find a dead rat lying across Robert’s empty breakfast dishes. The White Door isn’t meant to be a pleasant time, and while I can appreciate this in the context of Robert’s ordeal, it doesn’t make for an appealing experience. And that’s saying nothing of later story beats that become increasingly uncomfortable and violent. Intentional it may be, but in the end perhaps too grotesque for some.

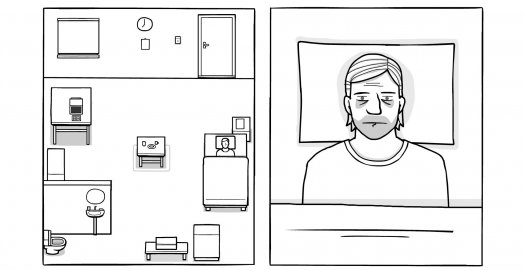

Unlike the Rusty Lake games, The White Door is presented in a split-screen, hand-drawn double-window style, with each half serving a different purpose. In Robert’s hospital room, the left frame shows a top-down view of the room while the right displays a close-up of the particular scene you’re currently interacting with, like the little table your food is served on, or the bathroom sink. During Robert’s dreams, the left frame is blacked out and only displays speech bubbles for dialogue, while the right side represents the visual enactment of the dream. In a neat stylistic choice, color in Robert’s daytime reality is extremely limited to indicate his bleak state of mind, making returning colors as the game nears its conclusion much more impactful. Robert’s dreams, however, are depicted in full color all along, as his resting mind isn’t affected by his current mental state.

Despite some common characteristics, The White Door is enough of a departure from other Rusty Lake outings to be of some interest even to those who are unfamiliar with (or not fans of) the surreal atmosphere and dark humor of those games, taking a far more serious tone and placing more emphasis on narrative. Puzzles are nothing particularly special, but the short runtime and non-traditional storytelling may even encourage a second playthrough to better connect its dots. Its divergence from the norm ensures it won’t connect with everyone, but it may be worth a closer look for those who appreciate the exotic – and occasionally grotesque – exploration of the subconscious mind.