An overview of genre history, by The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games: Part II

The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games is a stunning 500-page coffee table hardcover by Bitmap Books, filled with memorable pixel art and other classic scenes from the genre’s illustrious past. In honour of its second edition printing due out August 10th, bigger and better than ever with over 40 new pages of content, last week we debuted the first half of the book's introductory genre retrospective, reprinted with permission. This week, the conclusion.

(Note: Click on any image to enlarge.)

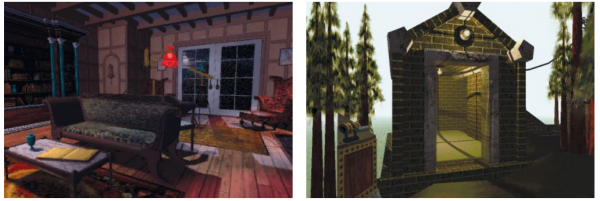

By this juncture the humble point-and-click adventure had begun to dominate the sales charts, at least on PC. However, the advent of CD-ROM technology, while enabling companies to enrich adventure games with voice acting and additional animation, introduced the first genuine threat to the genre’s commercial fortunes. Titles like The 7th Guest and Myst used CGI visuals and full motion video to create realistic-looking environments; viewed from a first-person perspective, this imagery drove gaming realism to a whole new level. Myst in particular was notable for taking the core mechanics of the point-and-click adventure – mind-bending logic puzzles and a gripping storyline – and placing them in an immersive first-person world fashioned using cutting-edge, pre-rendered graphics. Traditional hand-drawn 2D art, as attractive as it undoubtedly was, seemed old-fashioned when placed alongside these hyper-realistic worlds. Copycat titles inevitably followed as millions of PC owners invested in CD‑ROM drives to play this new generation of adventure. Despite the fact that such games were incredibly linear and often little more than glorified puzzle-solving exercises, they sold by the truckload and, perhaps, convinced companies like Sierra and LucasArts to rethink their approach to art design. Systems like SCUMM – with its verb tiles and inventory drawer taking up almost half of the screen – were the old way of thinking, and studios realised they had to alter the way their games looked; as much of the screen as possible should be used for eye-catching artwork, which meant streamlining the interface dramatically.

While LucasArts carved out a profitable niche creating cartoon-like adventures bursting with character and amusing one-liners, rival developer Sierra On-Line decided to take a somewhat different route with its 1993 title Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers. Designed and directed by Jane Jensen, Gabriel Knight had its moments of brevity but was primarily focused on the titular character’s investigation of a series of grisly local murders for his new book. Despite a rather convoluted interface the game was a commercial and critical success, and Sierra wisely used the storage potential offered by CD-ROM to include full voice acting with Hollywood talent that included Tim Curry, Mark Hamill and Michael Dorn. A 1995 sequel – The Beast Within – used FMV and digitised actors to great effect, while the third outing – 1999’s Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned – showcased 3D visuals that have, ironically, caused it to age far worse than its forerunners. 1994 would be a year of rest for LucasArts, but in 1995 it returned with two of its most ambitious projects to date. Tim Schafer helmed Full Throttle, LucasArts’ first game to be released exclusively on CD-ROM. The title took advantage of the increased storage of the format by including epic animated sequences (some of which made use of pre-rendered backgrounds and vehicles), full voice acting (including the talents of Mark Hamill), a lengthy storyline packed with unique locations, and a licenced soundtrack by American rock band The Gone Jackals. Full Throttle sold over a million units – a considerable success for LucasArts at the time. 1995’s other title was one of LucasArt’s biggest-selling yet, but endured a troubled gestation and ultimately disappointed many fans of the studio. The Dig was conceived by director Steven Spielberg many years previously but was shelved as he deemed it too expensive to film. In 1989, Spielberg attended a meeting at Skywalker Ranch with the objective of turning the idea into a game; it would take another six years for the project to see the light of day. Although it sold briskly upon its initial release, The Dig received some lukewarm reviews due to its difficult puzzles, uneven voice acting and lack of trademark LucasArts humour – although this was perhaps less of a fault with the game itself, and more to do with the studio’s run of amusing adventure titles which led fans to expect more of the same each time. Ironically, as LucasArts was taking flak for not sticking to its humour-led formula, titles such as 1995’s Flight of the Amazon Queen – an Indiana Jones-style caper clearly inspired by LucasArts’ output – hit the market to relieve some of the disappointment.

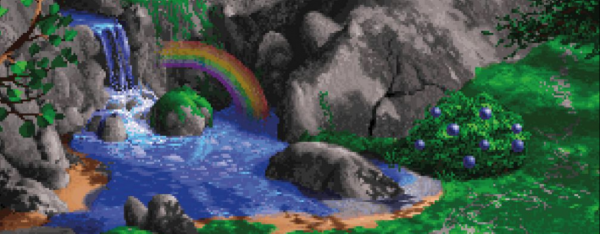

Indeed, the market for point-and-click adventures was burgeoning, and more and more studios around the globe were getting involved. In France, Delphine Software produced Operation Stealth (released in the US as James Bond 007: The Stealth Affair), Future Wars and Cruise for a Corpse, while Italian outfit Dynabyte contributed the offbeat Nippon Safes Inc. in 1992. Westwood Studios – previously famous for its strategy titles and the excellent first-person dungeon-crawler Eye of the Beholder – contributed the Legend of Kyrandia trilogy to the genre, a series which boasted some gorgeous 2D artwork from Rick Parks, who tragically passed away in 1996, aged just 46.

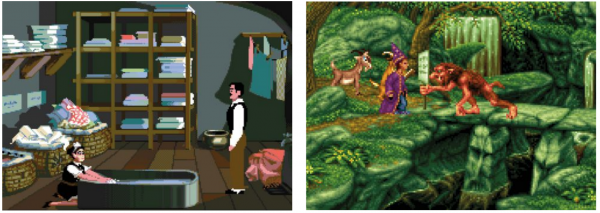

In 1993 – the same year that Sierra started the Gabriel Knight series – a comparatively small UK studio by the name of Adventure Soft released a title that would carve out its own niche. Simon the Sorcerer was the creation of a father-and-son team; Mike Woodroffe served as director and producer, while his son, Simon, wrote the dialogue. It copied the SCUMM interface almost to the letter, but infused the entire experience with a Terry Pratchett-style humour and some sumptuous artwork, created by a team of artists – Paul Drummond, Kevin Preston, Maria Drummond, Jeff Wall and Karen Pinchin – who worked separately from the main development team, producing black-and-white designs which were scanned into a computer and then colourised. While some critics grumbled about the game’s linear nature, Simon the Sorcerer was a smash hit for Adventure Soft and would later be re-released on CD-ROM with Red Dwarf’s Chris Barrie voicing the lead character. A well-received sequel followed in 1995 with Brian Bowles replacing Barrie as the voice of Simon, and in 1997 Adventure Soft launched The Feeble Files, a sci-fi comedy which used CGI visuals and featured the dulcet tones of Barrie’s fellow Red Dwarf cast member, Robert Llewellyn. A misguided attempt to update the Simon the Sorcerer franchise with 3D visuals in 2002 found a less receptive audience, but the continued popularity of point-and-click games in mainland Europe enabled German developer Silver Style Entertainment to produce the fourth and fifth Simon games in 2007 and 2009. Simon the Sorcerer 6: Between Worlds was mooted in 2014 – with Barrie returning on vocal duties – but in 2016 the project appeared to have stalled.

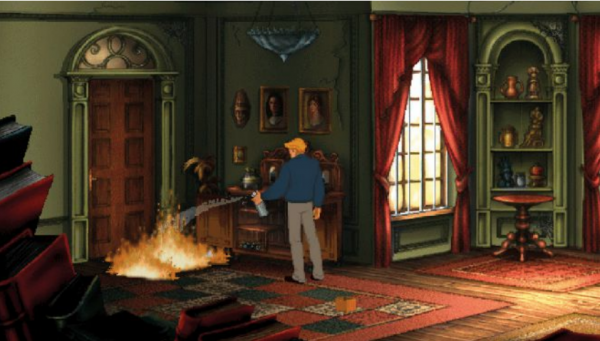

Core Design – the UK outfit which would later become famous for creating Lara Croft – released Curse of Enchantia in ’92, following up with its spiritual successor Universe two years later. Revolution Software, another British codehouse, also jumped on the point-and-click bandwagon with a title which attempted to cater for more mature audiences. Having released the well-received Lure of the Temptress in 1992, Revolution – co-founded by Charles Cecil – adapted its ‘Virtual Theatre’ engine to incorporate the designs of highly respected comic book artist Dave Gibbons, famous for illustrating the cult graphic novel Watchmen. The end result was 1994’s Beneath a Steel Sky, a game which is still regarded as a masterpiece of interactive storytelling to this day. Gibbons created the initial scenes using pencil, and these were later coloured in and scanned into a computer where they could be transformed into the gorgeous 256-colour, 320x200-pixel graphics seen in the PC version. The power of CD-ROM was harnessed for a full ‘talkie’ version of the game, for which Revolution enlisted classically-trained actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company. Despite spending two days recording more than 5,000 lines of dialogue, the results were deemed unsuitable and everything was re-recorded using voice actors instead – an indication of how serious Revolution was about making the project perfect. The hard graft paid off as Beneath a Steel Sky won praise for its adult tone, engaging dialogue and striking comic-book art style, and established Revolution as one of the world’s leading point-and-click studios. The company followed up with Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars in 1996, a title which had more in common with Sierra’s Gabriel Knight than it did with LucasArts’ brand of chucklesome adventures. Its storyline focused on the mysterious Knights Templar and – despite its cartoon-like visuals, courtesy of animator Mike Burgess and Don Bluth studios’ Eoghan Cahill and Neil Breen – Broken Sword dealt with some particularly mature themes. Predictably, sequels would follow, and even today Revolution pushes the franchise forward using current technologies.

By the middle of the ’90s, the unthinkable was happening: point-and-click adventures were beginning to lose favour with gamers. The real-time 3D revolution had begun in earnest, and a new generation of graphics cards were about to hit the PC market, making visually-opulent, three-dimensional titles the norm. LucasArts had dabbled in this arena with the likes of Star Wars: Dark Forces, X-Wing and Outlaws, but it continued to support the adventure genre with big-name releases. 1997’s Curse of Monkey Island was significant in many ways: it was the first outing in the franchise to lack the involvement of series creator Ron Gilbert, and the final game to use the SCUMM engine – although the massively refined ‘verb coin’ interface bore little resemblance to the system introduced in Maniac Mansion more than a decade earlier. The game was also notable for being the first in the series to utilise voice acting, with Dominic Armato bringing hero Guybrush Threepwood to life with a superb vocal performance. 1998’s Grim Fandango saw the studio move away from hand-drawn 2D visuals entirely and adopt a 3D approach using the new GrimE Engine, which mixed real-time 3D with pre-rendered backgrounds. Tim Schafer was once again at the helm, imbuing the game with a dark and witty sense of humour, which won it numerous admirers and plenty of critical acclaim. However, it underperformed commercially and put LucasArts one step closer to pulling out of the genre; 2000’s Escape from Monkey Island proved to be the company’s final contribution to the world of the point-and-click adventure, even if its cumbersome keyboard-or-joystick interface meant that it wasn’t technically point or click. Sierra encountered similar woes, too: 1998’s King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity used polygon visuals but failed to recreate the commercial success of previous games in the series. By the end of the decade Sierra had been sold to a larger firm and its original studio shuttered. While the company name would endure, it had little connection with the studio founded by Ken and Roberta Williams in 1979.

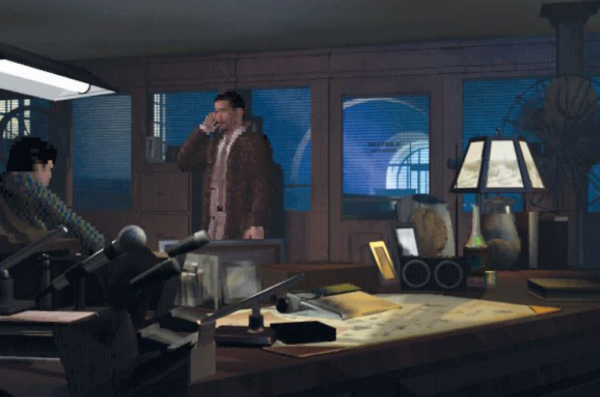

Westwood Studios – which had attempted to challenge LucasArts and Sierra’s dominance of the genre in the early ’90s with the aforementioned Legend of Kyrandia trilogy – stepped into the void left by its two erstwhile opponents with one of the most celebrated point-and-click outings of the decade. 1997’s Blade Runner was set in the same timeframe as the iconic 1982 movie of the same name, and used a combination of pre-rendered images and voxel graphics to concoct a rain-soaked 2019 Los Angeles. Even more remarkable was the fact that the game ran in real-time, unlike other examples of the genre, which would only move forward as the player solved puzzles and interacted with other characters. With sales of over a million units, Blade Runner provided a stay of execution for the otherwise ailing genre, which had seen its reputation plummet against the rise of the first-person shooter. LucasArts and Sierra had, by this stage, effectively walked away from the point-and-click adventure, and other high-profile projects – such as Jordan ‘Prince of Persia’ Mechner’s lavish, rotoscoped adventure The Last Express and Virgin’s technically stunning Toonstruck – were crushing commercial disappointments. However, in Europe the genre continued to be a viable proposition, albeit on a much smaller scale. Norwegian studio Funcom’s The Longest Journey arrived in 1999 to critical acclaim, while French firm Microïds enjoyed similar success with Syberia three years later. Both titles used high-resolution CGI visuals to superb effect, creating a deeply immersive experience while remaining true to the core mechanics of the genre.

Despite these minor triumphs, it seemed like the mouse-driven adventure had reached the end of the road; it would take two significant technological leaps to revive the fortunes of the genre. The first occurred in 2004, when Nintendo released its DS handheld. Equipped with a resistive touchscreen and stylus, the diminutive console revolutionised the way in which players interacted with games. It also provided the perfect platform for an adventure game revival, with Revolution Software’s Broken Sword getting a timely re-release on the system. This was accompanied by a new generation of titles which shared a vital connection with the glory days of the genre. Capcom’s Ace Attorney series – which actually began life on the Game Boy Advance in its native Japan – took puzzle-solving and character interaction and placed them within a courtroom environment, while Secret Files: Tunguska adapted the Windows version of the game for portable play. The Nintendo DS introduced touch-driven controls to millions of players, but the next step of this evolutionary process followed in 2007, with the launch of the Apple iPhone. Within the space of a few years, the App Store triggered a self-publishing explosion and saw companies like Revolution, LucasArts and Adventure Soft resurrect their classic franchises for the world of smartphones, an act which placed the genre back in the consciousness of gamers the world over.

Today, the humble point-and-click may not carry the same commercial weight as it did during the glory years of the late ’80s and early ’90s, but it continues to find a receptive and passionate audience. In Germany, where the distribution of violent video games has always been strictly controlled, point-and-click adventures have remained incredibly popular, and numerous companies have capitalised on the country’s appetite for logic puzzles and item collecting. These include King Art Games, famous for The Book of Unwritten Tales (2011) and The Raven: Legacy of a Master Thief (2013), and Daedalic Entertainment, which was responsible for The Whispered World (2009) and A New Beginning (2010). Outside of Europe there are pockets of point-and-click resistance, emboldened by the arrival of indie publishing avenues on both PC and consoles. In 2006, New York native Dave Gilbert founded Wadjet Eye Games, and in the years since, the studio has published many games using the open-source Adventure Game Studio engine, including The Shivah (2006), The Blackwell Legacy (2006) and Blackwell Epiphany (2014). Tim Schafer’s Double Fine Productions – the studio he founded after parting company with LucasArts – has recently remastered Day of the Tentacle, Grim Fandango and Full Throttle as well as producing Broken Age (2015), a point-and-click outing which used crowdfunding to raise its $3.45 million budget. Ron Gilbert, David Fox, Mark Ferrari and Gary Winnick joined forces to create 2017’s Thimbleweed Park, which is perhaps as close to an old-school LucasArts adventure as we’re ever likely to get. Meanwhile, Telltale Games has produced a series of episodic adventures based on properties as varied as The Walking Dead, Batman, Sam & Max and Monkey Island, helping these classic series to live on. Elsewhere, titles like Machinarium, Fran Bow, The Lion’s Song, Paradigm, Caren and the Tangled Tentacles and The Darkside Detective are fresh takes on the genre created by those who experienced the zenith of the point-and-click era from the perspective of wide-eyed players, and are now pushing the genre in new and exciting directions.

Modern-day adventures such as Heavy Rain, Life is Strange and Beyond: Two Souls owe a massive debt to point-and-click productions of yesteryear, too. So, despite falling from grace not so long ago, it would seem that the humble graphic adventure is finally back for good – even if the mouse and keyboard have perhaps been lost a little along the way.

So now we’re all caught up, but still just scratching the surface of what The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games has to offer. Tune in next week for an interview excerpt with Lori and Corey Cole, husband and wife creators of the acclaimed Quest for Glory series.

(Note: As an affiliate partner, Adventure Gamers gets a small percentage of proceeds from every copy of the book sold through our links. It's a win-win-win proposition!)