Review for In Other Waters

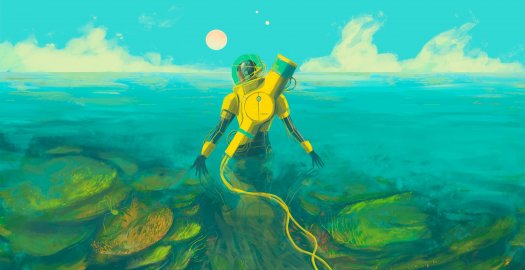

As living creatures ourselves, it’s easy to forget just how strange and downright miraculous organic life actually is. Earth is the only planet we know of where life has evolved, which is breathtaking in and of itself, but as it’s quite literally our own backyard we frequently become inured to the wild, wonderful strangeness all around us. Seeing something every day means it’s sometimes necessary to take a step back to appreciate it more fully. In Other Waters, by indie developer Gareth Damian Martin, is a superb game that aims to provide that helpful bit of distance, setting players adrift in an alien ocean and engaging their imaginations so that they might learn, observe, and understand. What starts as a simple mission gradually blossoms into an exploration of that first great mystery—the how and why of life itself—and a rumination on humanity’s place in the web of coexistence.

In Other Waters begins as Dr. Ellery Vas, a biologist employed by the Baikal planetary mining company, finds herself alone on a marine world designated Gliese 677Cc. She’s been summoned there by an old associate, Dr. Minae Nomura, with whom she shared a long-ago romance; Minae’s message said little except that Ellery was urgently needed, but on arriving all she finds is an abandoned base and an old AI-guided diving suit. Donning the suit as her only hope of navigating the underwater environment, Ellery soon makes an unbelievable discovery: the ocean is teeming with alien life, the first humanity has ever encountered. Surely this has something to do with Minae’s summons, but where is she? What was she doing here in the first place? And what is the AI that guides the suit, which seems far too complex and responsive to be a simple computer program?

Seeking answers to all of these questions but lacking ideas or resources, Ellery sets out to explore the Gliesean ecosystem and to document the life she encounters there, hoping that she’ll find some sign of Minae or the mission that brought her here. This simple biological survey, however, quickly becomes more complex as Ellery uncovers hints of something sinister in Gliese-677Cc’s past—something tied to Baikal, hidden away and meant to be forgotten. To learn the truth and survive she’ll have to rethink everything she’s ever known about biology, humanity, and existence itself, and to place her trust in an entity that she can’t even begin to comprehend.

The first thing you’ll notice while playing In Other Waters is that the visuals...aren’t, really. The entire experience is presented through what might, in another game, be considered the heads-up-display. There’s a simple dot-and-line topographical map showing Ellery's position and the places in the landscape with which you can interact, but that’s as much of the world as you’re allowed to see. Every action you take—movement, observation, specimen collection—is controlled via buttons and tabs alongside the map, so that you’ll never feel as if you’re controlling Ellery directly but rather responding to inputs and taking direction from her. The reason for this is simple: the dive suit’s AI, not Ellery, is the player character. Ellery will relay her intentions, goals, and needs to you, and your job is to help her fulfill them; as such, the interface consists of buttons that allow you to analyze the terrain for information and to relay it back to Ellery.

Every design choice appears calculated to place you in the suit’s mindset rather than the biologist’s; you relate to your surroundings not through sight but through data. Each function you use, whether it’s the map, the specimen collector, or the cutting torch you’ll sometimes have to employ, to name just a few options available, occurs off-screen, as the suit can’t visualize what Ellery is doing. That's not to say your character is a cipher, or that the AI's silence means it lacks a personality; despite your limited ability to communicate, you and Ellery will come to develop a kind of kinship over the course of the game's ten hours.

Ellery is desperately lonely here, searching for someone with whom she once shared a deep connection and unable to share her monumental discovery with anybody; the AI is her only companion on the whole planet, and Ellery will often take the opportunity to try to engage it in conversation. She does most of the talking, ruminating on what she’s seen so far and asking questions for it to weigh in on; as the AI you can’t speak back directly, but you can indicate a yes or no answer. The more Ellery speaks, the more insight you’ll gain into her mindset and her character, and—mirroring the AI’s own feelings—you’ll do all you can to communicate back with the limited responses available to you.

Of all the suit's functions you'll need the scanner most often, which reveals points of interaction on the map (usually geographical features, lifeforms, or nodes to which Ellery can move). New discoveries appear in white, turning yellow once you click and learn about them. The map display gives you a very basic idea of the landscape you’re traversing, but it’s a guide, not a true visual representation of the seafloor: structures and lifeforms appear as simple dots and triangles, with little variation. Movement is achieved by locating new nodes and directing Ellery there using the suit’s compass; you don’t "control" Ellery so much as you plot a course for her to follow. The controls are all mouse-based, so functionally it’s not much different than standard point-and-click, with the caveat that Ellery can only move to specific points on the map. Still, the extra layer of having to search for your next navigable spot helps detach you from Ellery’s headspace and place you fully into the role of the guide program you are.

Ellery’s interest in the planet is primarily scientific—personal investment in the mission aside, she’s still a biologist making first contact with alien life—so the majority of the tasks you’ll perform involve observation, analysis, and specimen collection. Encountering a new lifeform (usually symbolized on the map by a dotted X) necessitates clicking it so that Ellery can make basic notes about what she sees, which are then displayed for you to read. Once you’ve observed enough of a given species—both by encountering living specimens and by collecting various fragments, leavings and droppings from the seafloor—Ellery will name and categorize it in a full report, with information on its lifecycle, appearance and function within the larger ecosystem. She’ll also include a few pencil sketches to give you an idea of what it looks like.

Gliese-677Cc’s environment is diverse, rich, and teeming with lifeforms that feel truly alien, including fungal stalks that communicate by humming; vast, net-like colony-creatures who encircle and shock their prey; and crab-like rock-eaters who survive anoxic environments by encasing themselves in bubbles. Nothing in the Gliesian environment ever comes off like a reskinned Earth creature; you truly feel as if you’re wandering through a new and unexplored world, where the only answers you can hope for are the ones you find yourself.

Each species you encounter is another mystery to solve, and new specimens provide tantalizing clues when you track them down. Ellery’s narration of her findings brings the creatures to vivid life, so that it came as something of a surprise to suddenly realize I hadn’t actually seen a single one of them; the descriptions are so detailed and evocative that I was able to picture each organism as if I’d encountered it myself. This has the unfortunate side effect of rendering the pencil sketches Ellery includes in her dossier a bit underwhelming; I felt so personally attached to the colorful, lifelike images the game had conjured in my head that I resented the diagrams a little for not living up to them. Still, this planet is a triumph of the imagination, and the fact that it feels so alive and full of depth as a game world with hardly any visual component at all is astounding.

As you continue to learn about the Gliesian ecosystem, you’ll be able to see and do more in this world. Discovering how different species interact is necessary to progress past certain obstacles; for instance, one species of obstructive fungal growth retreats from the presence of certain spores, allowing you to clear a path by collecting and deploying the latter. Specimen collection is a simple and intuitive process: when you find an object in the environment that you’d like to take, you can activate the collection mechanism, which appears as a small sonar display with a ping to represent the specimen. It’s then a matter of centering the display on the object in question and pressing a few buttons to put it into your inventory; from there you can drag and drop it onto the map to have Ellery use it in the environment.

Specimen collection will sometimes prove necessary for Ellery’s very survival. Her suit can carry finite amounts of fuel and oxygen which decrease the longer she’s out, but certain specimens can be processed to replenish them. (Fuel decreases steadily, but the suit's rebreather system means you'll only lose oxygen when you enter an anoxic environment). Both levels are displayed alongside the map, and when either gets low the meter will flash to alert you. Running out of either isn’t actually fatal—the suit activates an emergency protocol to bring Ellery back to the ship for recovery—but it will mean being dragged away from wherever you were and having to navigate your way back. Thankfully you’ll have the opportunity to refill your tanks at several “way stations” that Mirae erected during her own expedition, so if you’re strategic with your travel planning and resource use, you can go the whole game without running out.

The way stations also offer the opportunity for Ellery to travel back to the ship, which serves as a safe zone and a base of operations. This is portrayed through the AI's perspective as a series of wireframe images representing the vehicle’s various decks, with nodes through which you can access functions of the ship's computer. These allow you to read through Ellery’s scientific observations, open her personal journal to see her reflections on your findings, and analyze the specimens you’ve collected to discover their possible uses; you can also store items you’ve collected onboard if you want to save them for later.

The ship is the only place where you can access the full “world map,” which is unfortunately less helpful than it should be. You can use it to get a general idea of what direction you need to head, but since you can’t open it out in the game world, you’ll have to remember everything yourself. The problem is compounded by the fact that the map doesn’t correspond exactly to the terrain you’ll be traveling, meaning it’s only useful for getting your bearings and not for plotting an exact course. Entering a new area updates the world map to point you toward undiscovered specimens, but in at least one case for me the marker barely lined up with the actual location. I spent a good long while traveling in circles before I gave up and asked the internet where to look. (Judging by my search results, this has been a common problem.)

Discussed on their own, all of these elements could add up to little more than an exploration sim with a novel gimmick, but In Other Waters is much more than that. Ellery is an active and present protagonist, and her (unvoiced) monologues and journal entries—along with some (likewise unvoiced) audio logs you’ll find scattered throughout the environment—ensure that you’ll never get so lost in the novelty of discovery that you lose track of the game’s narrative. It’s a story about many things: loneliness, both on an individual level and as a species in the cosmos; sentience, thought, and intelligence, and the possibility that we understand none of them; the fragility and mystery of life itself, and the necessity of preserving it in the face of a system that grants it little value.

It’s all full of beauty and wonder, but it’s also mournful by its very nature: Ellery has come here chasing a lost love only to find herself alone again, and the joy she feels at her new discoveries is tempered by the terrible revelations and the sense of responsibility that accompany them. The minimalist synth score helps to embody the constantly shifting emotions you’ll feel, simultaneously evoking both the peaceful sound of ocean waves and the painful, longing beauty of whalesong.

In Other Waters is also mindful of the parallels between its fictional story and real-world events, though it never grinds its narrative to a halt to draw attention to them. While you wonder in awe at the joyful vibrance of the Gliesian ocean, the game finds ways to gently remind you that our own planet is home to an equally fascinating underwater world, just as full of complex and incredible creatures as any we can imagine, and just as endangered by human folly as the worlds touched by the Baikal company.

The script never preaches, nor does it artificially shift its focus toward issues facing us in the 21st century, but it doesn’t shy away from the similarities between its own scenario and the one playing out before us here at home. Earth in Ellery’s time has been brought to the brink of destruction by climate change, resource depletion and the destruction of ecosystems; those who remain alive have been confined to ocean-borne cities that can withstand the risen tides. Humankind has gone to the stars not to explore but to escape. The implication for our own time is clear, and as the story unfolds it will surely resonate on a personal level.

On paper, In Other Waters sounds like science homework: look for specimens, produce reports, analyze topographical maps, and rely exclusively on data and machinery for all of it. In action, it’s a passionate ode to the impossible beauty and wildness of nature, and a reminder that our species’ great intelligence carries a burden of responsibility to the world (or worlds) around us. I’ve never played a game like this one, and I don’t expect to again. I’ll not soon forget what I saw on Gliese-677Cc—even if I didn’t see any of it.