Ragnar Tørnquist – Draugen interview - page 3

As Ragnar Tørnquist and I sat down to chat at GDC in San Francisco about his upcoming game Draugen, I got the feeling he’s had to explain himself a lot lately.

“This is a departure for us,” he warned. “It’s obviously a first-person game, and we like to call it an adventure game, but I’ve had this argument with people—it sort of comes down to, do you consider Firewatch to be an adventure game? Do you consider [What Remains of] Edith Finch or [The Vanishing of] Ethan Carter to be an adventure game? [Draugen is] not a game about puzzles. It is a game about exploration, dialogue, solving a mystery.”

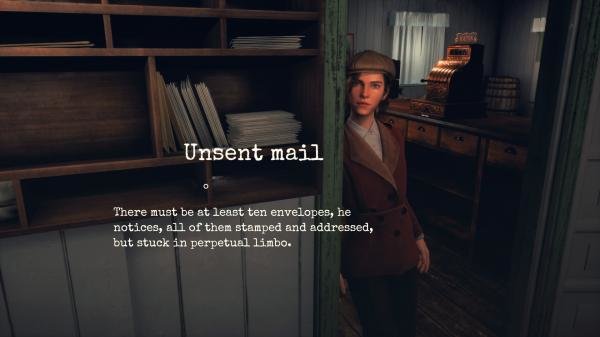

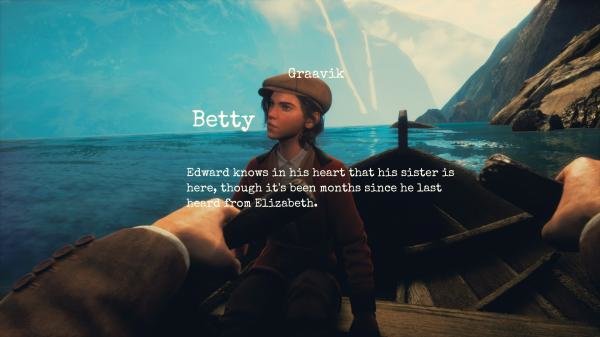

Set in 1923, Draugen is the story of an older man named Edward and his companion, a young woman named Lissie, on a search for Edward’s missing sister. “We sort of invented a genre called Fjord Noir; it mixes a gothic detective story with the fjords and mountains of western Norway,” Tørnquist explained. “You don’t know the relationship between [Edward and Lissie] as the game begins. It’s obviously not romantic—she’s young, he’s much older; they have more of a father/daughter kind of thing. But she might not be his daughter either, and that’s part of the mystery.”

The game will open with Edward and Lissie’s arrival in the same tiny fishing village in western Norway where Edward’s sister, a journalist, visited before her disappearance. You soon reach a house where you’re supposed to be staying, but nobody’s there. Which, of course, means it’s time to snoop: “You start to peek into these people’s lives a little bit, and to learn about this environment, but it’s filled with that overhanging feeling that something is wrong, and that grows over the six days you spend here.”

Extensive dialogue has always been a hallmark of Tørnquist’s games, and Draugen looks to continue that tradition. He cited the teen drama Oxenfree as an influence, particularly the way the characters are “engaged in dialogue on a continuous basis … what we’re trying to do is create the sort of overlapping dialogues that people [have] in real life.” Like in Dreamfall Chapters, as you choose from Edward’s dialogue options, you’ll get a glimpse of his motivation for making that statement or asking that question, so you won’t be caught off guard by the words that come out of his mouth.

“The cool thing about this game, instead of a character that talks to himself and that feels a bit artificial, he’s always talking to Lissie,” Tørnquist explained of the dynamic between Edward and his companion. “When he’s describing things, when he’s investigating—there are constant conversations going on all the time, if you want. Or you can not interact with Lissie and wander off and keep silent. There’s so much of the story here that’s hidden; it’s there to find but it’s not there to be pushed onto you. You can go through the entire game and not have learned half of what the story is about.”

Draugen is “not really a branching game, but the things you say matter and are picked up on later.” When talking to Lissie, you get to choose when and how to interject, whether to interrupt or let her finish talking, which thread to pursue. Or you don’t have to answer—you can stay quiet while Lissie carries on a one-sided conversation. “It’s definitely the most important mechanic in the game, how you interact with Lissie,” Tørnquist said, adding that what starts as a light, bantering relationship between the two of them will shift and change as the story gets more serious.

But while it promises to be a dialogue-heavy game, Draugen is mainly about exploring the environment and investigating the mystery. “And there are two mysteries here, or three: the mystery of where’s Edward’s sister; where’s she gone to? She’s a journalist, she traveled to Norway some months ago and he hasn’t heard from her. There’s also the mystery of this village that appears to be completely deserted; what happened here? And then it all ties together with the relationship between these two characters.”

While you’re exploring, Lissie is only a key or button press away. “It works depending on distance and what the situation is; it’s either a way to sort of converse with her, interact with her, or to call out to her, to find out where she is,” Tørnquist explained. “It can even be a guidance through the world: instead of having an arrow that tells you where to go, you can call her and then you find out where she is. And we play with that mechanic over time. She’s mostly there, but then sometimes she’s not, and then the button changes behavior, and that affects a lot of what the story is about.”

I was surprised to hear Draugen will be out in May—that’s soon! Conceptually, Red Thread has been planning this game for years, but it’s only been in active production for less than a year. The playtime will reflect this abbreviated schedule, with Draugen clocking in at around three hours. “It’s a mood piece more than anything,” Ragnar said. “It’s all about these two characters, who they are, and being inside the head of this strange man and trying to decipher who Lissie is and what their relationship is.”

Read on for more insights into Draugen, Ragnar Tørnquist’s feelings about Dreamfall Chapters a few years later, and what’s next for Red Thread Games.

Emily Morganti: It seems like you keep having to explain, “This really is an adventure game!”

Ragnar Tørnquist: In terms of the adventure thing, it always feels like … I don’t want to call it gatekeeping, but there seems to be an idea of what an adventure game is sometimes, very specifically. We’ve been called out on that: Dreamfall Chapters was not an adventure game, or Dreamfall wasn’t an adventure game—

Emily: Yeah, you’ve been bucking that for a long time.

Ragnar: It’s not because we [don’t want to] make traditional adventure games, it’s just that I like telling stories with new mechanics. To me a game that’s about conversation and character interaction and exploration, that is an adventure game. Puzzles are not what define an adventure game. And there are light puzzles here; it’s more sort of about figuring out where to go and when to go there, in a way. But, you know, traditional puzzles, we didn’t want that to get in the way of the story. This is not a puzzle game. It’s not Myst. It’s a story.

Emily: How did you come to that decision? Was it when you were working on Dreamfall Chapters? At what point did you say, ‘I want to try something totally different?’

Ragnar: We sort of always want to try something different, but with Dreamfall Chapters we sort of—you know, that was a long hard struggle, and we did something that we’re pretty proud of, even though it has its ups and downs, but we definitely didn’t want to do the same thing again, or even stay in the same universe. So Draugen actually was born early on in development of Dreamfall Chapters, just to give us something to look forward to, to work on after we finished that, but it’s changed a lot over the years. And it used to have more puzzles, but I think every time we implemented something that felt puzzle-like, we felt, ‘This gets in the way of the story; it just stops it.’ And with this game we want everybody to get through it, we want people to get through it in one, two, three sittings, and just enjoy the story, and not to have any barriers. So it’s not a game that I think anybody’s going to struggle to complete; it’s more, does the story grab you?

Emily: How do you think the Dreamfall audience will react to that?

Ragnar: They’ve already been sort of conditioned that we don’t necessarily make traditional puzzle-driven adventure games. The first-person thing might throw some people off, but you don’t have to have fast reactions or anything like that.

Emily: Why did you decide to do first-person?

Ragnar: Because you’re inside the head of a character, it’s very different. You’re experiencing sort of this person’s inner life. And the focus is on this other character, Lissie, in the world. If you’re doing third-person you’re removed a little bit from the character, and the companion character becomes even further removed; you’re two steps away instead of one step away. And also I’m a fan of a lot of these first-person narrative games and how that genre’s evolved from, you know, Gone Home, which is very simple and simplistic these days—you go back to that and you’re like, it doesn’t have a lot, it just has a really great atmosphere and a great story. And then you look at something like Edith Finch, which is pushing that in a completely new direction. But I think [Draugen] is closer to Firewatch, mixed with a bit of Edgar Allan Poe and fjords and mountains.

Emily: In doing first-person, are there limitations you weren’t expecting?

Ragnar: There are challenges, especially when it comes to animations of the head, things like that that you have to deal with. We questioned whether or not we should have a body, and we don’t, because it’s kind of disconcerting sometimes to look down and see a body, and it’s a lot more work. We are doing the hands, which we feel is important, so you can see [Edward’s] hands and you get a connection to the character. We haven’t implemented it yet, but he’s going to have glasses as well, and he can take his glasses off. There’s a connection and an immediacy, but in a lot of first-person games, too, your character is sort of like a cipher, but we’re very much into giving [Edward] a personality. So if you look at a mirror you can see him, and if you go to drawing spots in the world, you can sit down and illustrate, and we actually cut to a third-person camera, just to give you an idea of who he is and to see him in the environment.

Emily: So there is a character model, and we’ll see him occasionally?

Ragnar: There is a character model, yeah. And I think that’s sort of—we took that expense, too, because I feel like these games that have nobody around—in Firewatch, I know that’s the idea, but I was kind of disappointed to not meet the other character at the end; it felt like it stopped just before I wanted the game to stop. So I think it’s nice to be able to explore this world together with somebody else; it just feels different.

Emily: That also brings to mind a Walking Dead, Lee and Clementine relationship.

Ragnar: That’s a good comparison, I think, although, you know, you’re more protective toward [Clementine] than with Lissie, who’s very independent. Edward is sort of the one who needs protection sometimes, because he’s sort of—he’s a bit dull, he’s a bit slow and old and dull, and he doesn’t like climbing things or exploring or doing anything really. He’s a recluse, and he struggles with his own issues; he’s not comfortable around people, he’s not comfortable out in the world. He’s barely left the house in thirty years. His sister disappearing pulls him out of his shell and he has to go, he has to travel halfway around the world and face this completely new reality. And a lot of the game happens up here [gestures to head].

Emily: I want to ask questions about the story, but I feel like there’s nothing I can ask—

Ragnar: You don’t! I think this is the kind of story that the less you know, the better it is. Everything I’ve said, you discover in the first five minutes of playing the game, but beyond that we do want people to be surprised, and engaged in the mystery and in who this character is. It really is more of a game about people than it is about a greater mystery; it’s about the mystery inside rather than the mystery outside.

Emily: Your decision to make a game that’s more… I don’t want to say “walking simulator”—

Ragnar: That’s a terrible, terrible—

Emily: I didn’t say it!

Ragnar: But a lot of people do; that’s a tag that exists in Steam.

Emily: And I hate it! I hate when people say, “No, we’re going to embrace it”—

Ragnar: No, it’s the wrong thing to embrace, because it’s so much more than a walking simulator. We’re not simulating walking. A game where you have to press the keys to get the legs to walk, that’s a walking simulator! I like to think of it as narrative exploration, or first-person exploration. But it’s also about more than that: it’s about talking to characters, it’s an adventure game! Like, who cares if it’s first-person, who cares if it doesn’t have hardcore puzzles? It’s an adventure.

Emily: Okay, so your decision to make a first-person exploration game, does that come at all from changes in what people are playing, or what you saw for sales with Dreamfall Chapters, or what you’re seeing with YouTube, any of those types of influences?

|

Dreamfall Chapters sold over half a million copies |

Ragnar: Not really, because Dreamfall Chapters has done very well; it’s sold half a million copies. If we were smart we’d do that again. [laughs] But to me it was more like, I want to explore a new genre, the team wanted to do something new. It’s an exciting genre; it’s just a chance to do something a little bit different, to put our stamp on that. And there aren’t that many first-person exploration games coming out.

Emily: Not enough, in my opinion.

Ragnar: I mean, Campo Santo has In the Valley of the Gods, and that looks a bit similar with the companion character, but there’s very little else. So it’s sort of, yeah, why not do something that people seem to enjoy, and it’s a story that we wanted to tell, and it would only work as first-person. We don’t necessarily make decisions based on marketing trends. We feel if you make a game that has a good story that hooks people, people are going to play it regardless of what the genre is. There’s always a market for that.

Emily: I hope so. I think games like Tacoma had trouble—

Ragnar: Tacoma struggled a lot. But I think that has to do with—and I did buy it; I haven’t played it yet—but from what I’ve read, it’s a really good game, but I think they maybe struggled with how to present the story, and it was a space station which is hard to do. People have been on space stations [in games], while Gone Home was in a family home in the ’90s. That felt approachable and unique at the same time, while Tacoma felt like, yeah, you go up to a space station… I mean, god bless them for making that game, but I feel like it was a harder sell than Gone Home in a lot of ways.

Emily: Which you wouldn’t necessarily think. You would have thought that Gone Home would be the harder sell.

|

Draugen can be compared to What Remains of Edith Finch (pictured) in terms of environmental storytelling focus |

Ragnar: Yeah, absolutely. But I think also, they decided to say, we want to tell this story, and we’re going to tell it. Edith Finch I think also struggled with sales in the beginning, but that’s such an ambitious title. Have you played it?

Emily: I started to and I couldn’t get into it. I had a lot of trouble with the controls.

Ragnar: Yeah, because you have to pull and push everything.

Emily: Yeah, and I got through one of the first sections and it was making my teeth hurt.

Ragnar: It’s a hugely ambitious game; they do so much stuff, and that must have cost a whole lot of money and a whole lot of time to make that game.

Emily: You liked it?

Ragnar: I do like it, I do like it, simply because of the ambition, and I like the story. Again, it’s sort of a family story, and I like games that are anchored in the real world; that’s always interesting to me.

Emily: I like that too, and actually in Dreamfall, my favorite parts were in Stark.

Ragnar: The domestic stuff.

Emily: Yeah, the fantasy wasn’t as interesting to me; I was more interested in the stuff that’s happening in the real world, even though it’s a futuristic, not-real version of the real world.

Ragnar: Yeah, and I think if I was going to do any changes, maybe doubling down on the domestic aspects, but with Dreamfall Chapters we were sort of committed to a story that had to be told, and that story had been decided a long time ago, so there wasn’t a lot of freedom in terms of… well, we have to do this. Not that it’s a bad thing, but we have to do it.

Emily: And the added layer of having the Kickstarter and having all these people you’re answering to.

|

Dreamfall Chapters tripled in size between original concept and final game |

Ragnar: Yeah. New company, new team, tight budget, huge expectations, a game that grew over time because we really wanted to—I mean, that game tripled in size, and it didn’t triple in size because we’re terrible at planning, it was because we felt we owed people. Especially since we went episodic, we’re like, oh shit, now we really have to go above and beyond, and we kept doing that. The final episode, we didn’t even set ourselves a deadline; we said we have to do this right, we have to conclude this right, so we spent six months on it and all of our money in order to just, basically, get that done right.

If anything that’s what makes me a bit sad; people criticize it—a lot of people love it, too, the rating is very high, so obviously people do like it, but it’s a feeling like people were cheated out of something? But we were really all in; we just wanted to make a game for the fans, you know? And I think also the game sort of got… it started pretty good, but then it sort of got off rails, but then it got back on rails toward the end. I’m proudest of episodes 4 and 5 and how they managed to conclude the story we wanted to tell in a proper fashion that we can actually close the book and say, ‘We’re done now. We don’t have to do anything more, because we did what we were supposed to do.’

Emily: Which, after ten years or whatever, it was nice to be able to close that book.

Ragnar: Yeah. I mean, of course some people weren’t happy, but I think most people were. And you know, you always get the thing where it’s like, oh, where’s April Ryan’s story? That was The Longest Journey! That’s also why we decided to move on, I think. To be able to get past that a little bit and do something fresh.

Emily: With no expectations.

Ragnar: Exactly. So hopefully, The Longest Journey and Dreamfall fans will play Draugen and get something from it. And the vibe, and the mood, is similar to what we’ve done in the past. It’s just something fresh, and it concludes. There’s no cliffhanger or anything; it’s one and done with, you know?

Emily: How do you feel about episodic games now? Would you do it again?

Ragnar: No. I don’t think so. I think episodic is also struggling now. Life Is Strange 2, is the second episode even out?

Emily: The second episode’s out; it came out in January.

Ragnar: Oh did it? I missed that. They took a long time.

Emily: I think it was four or five months.

Ragnar: Exactly, and I think people are tired of that. And I know they’re also struggling with the sales of that, compared to the previous one.

Emily: I really liked the teen girl story, so when Life Is Strange 2 was announced and it was going to be about boys, I just wasn’t that interested. And I was so surprised when I played it—the first episode is so good. So then I was kind of sad that it’s not getting as much attention.

Ragnar: I was also disappointed to see that; like really, you’re going to do boys now? I thought the idea with Life Is Strange is you do something a little bit different. But I’ve heard really good things.

Emily: It’s really good. You should play it.

|

Telltale's The Walking Dead may prove to be episodic gaming's greatest achievement but also a victim of its own success |

Ragnar: I do think it shows that episodic gaming is dead. I think it might come back with the streaming model and the subscription model—not only subscribing to a single game, but to a service, because then these episodic games could be part of a larger package that you’re paying for. So that could be interesting. But the demands of making [an episodic series]—it’s probably one of the factors contributing to the fall of Telltale. That constant production pressure is not healthy, and is not good, and players are shouting out for new content, which puts the team under immense pressure. We had to basically abandon our schedule and say, look, we have to take the time, we have to, because we can’t keep churning these out every three months; it’s not going to work.

Emily: There are a lot of conditions that come in to make it very unhealthy for the people who are making the games. Pressure from the company, pressure from people on the internet.

Ragnar: Yeah. On [Dreamfall Chapters], we decided to only do a season pass; we never sold individual episodes, because we knew there would be a huge fall-off. So we’d rather say, ‘You commit to it and we’ll commit to it.’ But that’s also risky if you’re doing an episodic game selling season passes and you go, ‘Nope, two episodes and we can’t afford that anymore.’ That’s bad.

Emily: A big problem right now, for getting attention for adventure games, is that streaming has become so prevalent. Once a game like Draugen has been streamed, why should anybody go out and buy it?

Ragnar: Exactly. We don’t mind people streaming it, and all those people watching it and getting the story, fine, at least they know that the game exists. But they’re not going to buy it afterwards. Why would you? What’s the excitement now, unless you want to support us, and most people don’t think like that. But I think there’s a huge market for single player, shorter narrative games, and it’s proven. It’s a shame that Telltale disappeared but I think that market is still there for other people to pick up. So our vision is like, we would love to continue that tradition, but do it differently than Telltale did it, and not double down on only external IP, and not do episodic. Because they grew fast in directions that they maybe shouldn’t have.

Emily: Making Draugen in a short development cycle, working on it for a year and then getting it out, is that something you’d like to do regularly? A new game a year?

Ragnar: Yeah. We do, and our next game—we’ve started work on it already—that’s the game I decided, when Trump was elected, that we had to make, because as game developers, what can we do in this world? I feel like we’re not doing anything to contribute positively to the world we’re living in. So our next game is an adventure but with some action elements, that’s very us not staying in our box and saying 'fuck it,' we’re going to rise up and we’re going to try to resist a little bit and make a game that, even if it makes ten people change their minds when election day comes around, great. So it’s set in our version of America, ten years into the future, and we’re excited about that.

Emily: Do you have any concerns or thoughts about being non-Americans making a game like that?

Ragnar: I think that’s a good thing, because we have an outside perspective on it. And it’s not like—maybe people in America think that because we’re from the outside we don’t really understand what’s going on—

Emily: You probably see it better than we do!

|

Ragnar Tørnquist |

Ragnar: I wake up and look at Twitter every morning, and I read the Washington Post every morning, and it’s all that concerns me, because everything that happens [in the U.S.] affects us so much. Politics in Norway is quite boring, in a good way. But Brexit and U.S. politics, that’s what we get fed every day. And this game is not really about the real people in American politics, it’s more about the emotions of it and the feelings of it. Of course we’re going to get that criticism, of course there’s going to be a lot of people yelling at us. Fine. We’re not afraid of that; we’re used to being yelled at. If you go on the Steam page for Dreamfall Chapters, most of the threads there now are about the politics of Dreamfall Chapters, how the game is Marxist propaganda and stuff like that. Which is ridiculous, because it actually turns out the Marxists are terrorists in that game! But it means people are sort of—they see a single criticism of right-wing politics and they take it as leftist propaganda.

Emily: It’s a small group of vocal people.

Ragnar: It is a small group, and it’s not even Americans for the most part. There are a lot of progressive people as well, but it’s that sort of conservative gaming audience, which is tiny, but it’s vocal.

Emily: Do you try to avoid controversy with those people?

Ragnar: Oh no. No, I dive right in. And you see that on the Draugen Steam threads as well: oh, don’t support Red Thread Games, because as a company they’ve dared to speak out, and companies should never speak out, companies should be neutral. No, fuck no. We’re independent. Who cares? We can put those beliefs into our games; we’re not afraid to stand for something. Look at TV, look at Handmaid’s Tale. That doesn’t have a message? Of course it has a message. And that’s made by a huge corporation. So why are games supposed to be apolitical, why are games supposed to be never about something? ‘Keep your opinions and politics out of my games?’ It makes me so furious.

Emily: And if you don’t want to play that game, don’t play that game.

Ragnar: Don’t play that game! But even that is sort of like, no, do play the game, and feel free to disagree, but don’t tell us that we can’t have a message, that we can’t have a personal story. But you know, that said, we’re not [making] a game that’s setting out to preach a political message, we’re trying to just present the point of view and to also present different points of view, and let the players figure it out for themselves. But of course we have our beliefs. That’s going to color everything we do.

Emily: It’s refreshing to hear you say that.

Ragnar: Yeah, it makes me angry sometimes that people are like—the fear of politics. And this is not a criticism of, for example, Ubisoft, but I don’t know if you heard their statement about Division 2, which is set in Washington D.C. after an event that divided the country, and they say Division 2 is not a political game. Your game is in Washington D.C., shooting people. How is that not political?

Emily: Own it.

Ragnar: Own it, exactly. And it’s a shame that games are not there yet, when movies and TV do have messages, and they’re confident, and that’s great, and people accept that.

Emily: And they have for decades.

Ragnar: Star Trek, in the ’60s, had progressive messages! And now people are—I don’t know, it angers me. I like talking about it, it’s just frustrating. But there are publishers who are afraid of this kind of stuff, so we’re very up front about it, so if that worries you, scares you, don’t work with us on that game, because that’s what it is.

Emily: You didn’t do a Kickstarter this time around. Does that mean Red Thread is self-sufficient? Is everything going well as far as being an independent company?

Ragnar: It’s going. Like most indie developers, we’re getting by. It’s hand to mouth. We’re making enough money to pay our employees and to have free lunch for people everyday, but that’s it. We’re not paying ourselves a lot of money. We just want to make games and tell the stories. We don’t expect to ever create massive hits, because that’s not our motivation for making games, which is telling stories. Our hope is, at some point, one of these games is going to be huge and we can have a little bit more security, but that’s not indie game development. Nobody has security.

Emily: I think that’s a trade-off when you want to make adventure games, or story games—this is the size of my audience; I want to make a game that maybe attracts a little bigger of an audience, but this is what I’ve got.

Ragnar: The audience is millions, but you’re never going to reach everybody with a single game. Telltale did really well; I think there it just became a question of maybe it wasn’t sustainable over time, the amount of games they were making.

Emily: That, and I think The Walking Dead was a huge hit based not only on the fact that it was a great game—

Ragnar: It was The Walking Dead at the right time.

Emily: Right, and then those numbers don’t necessarily grow, but that was viewed as the new baseline instead of an anomaly.

Ragnar: And that’s a dangerous thing to think, that the baseline is the huge success. You don’t want to do that. But we do feel there’s a big market for what we’re doing, and we’re also always mixing other genres into it, so we’re not afraid to have action or to have other types of elements together with the storytelling and the character development. Hopefully at some point I can say we finally did it; we can have a massive hit and we can relax and do what we want to do for the next decade. Because, yeah, that would be nice.