A Sierra Retrospective: Part 3 - From Atari to the Magic Kingdom

A Sierra Retrospective

A lookback at legendary game companies or series

When you think of Sierra you might not necessarily think of the Atari 2600 or the Commodore 64, but both systems had a big impact on the fortunes of the company.

From the earliest years of its life, the Atari 2600 console was the biggest video game platform in America. By 1983, six years after its release, the revenue from game sales had skyrocketed and an ever-growing number of third-party developers had started producing games. Sierra, or Online Systems as it was then called, was one of those companies. The market quickly became oversaturated, and with few quality controls in place, a string of high-profile flops such as Atari’s infamous E.T. ensued.

On the personal computer front, the ongoing price war between Commodore and Texas Instruments (TI) hit new heights in 1982. Commodore reduced the price of their Commodore 64 computer to only $300, rocking the fledgling game industry. Customers suddenly wanted a full computer system, not just a game console, and could now get one for a similar price.

TI’s TI-99/4 personal computer was an early casualty of the price war and was discontinued in 1983. This, combined with oversaturation and the growing list of poor quality games, caused what is now referred to as the North American video game crash.

With TI pulling out of the game market, Ken Williams, CEO and founder of Sierra, bought their license to create computer games based on Disney characters. Acquiring the license allowed Williams to bypass the usual up-front licensing payment Disney required and only have to pay royalties to them on sales.

At that time, entire companies were folding with warehouses full of now worthless Atari, Vic-20 and Colleco cartridges. Sierra didn’t go under like so many of its competitors, but the business suffered a major financial crisis.

Al Lowe, creator of the Leisure Suit Larry games, remembers the time clearly. “One morning I went to work and there were 120 employees and that afternoon there were 40. So it was a tragic blow.”

When Lowe was let go like so many of his colleagues, Ken Williams made him a deal to keep him employed though he couldn’t afford to keep him on staff.

“A lot of those guys were given the same offer I was given, which was you’re not going to get a salary but I will pay you advances against future royalties,” Al says. “As you finish parts of the game, bring it in and we’ll give you more advances, just like a book author would do. You get an advance up front and additional checks as you go along and you finish it.”

While a lot of people didn’t take Williams up on the deal, Lowe did. He recalls, “I went home and worked my ass off. There were several other guys that did too.”

Ken had always envisioned Sierra as being a combination of Disney and Microsoft, so the Disney license was a natural fit at the time. Their initial contract allowed for four games based on major Disney characters.

|

Donald Duck's Playground |

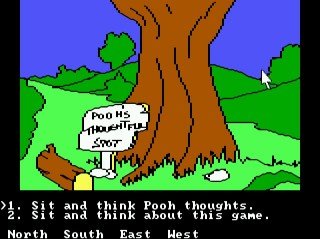

In 1984, Sierra released three educational games under license to Disney. While Donald Duck’s Playground would best be described as a skill-based game for children, and the Goofy Word Game was never released, both Mickey’s Space Adventure and Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood were adventure games in the style of Sierra’s earlier titles (games such as Cranston Manor and Timezone).

Al Lowe worked on the all the Disney games. He composed the soundtrack for Mickey’s Space Adventure and was the sole designer and programmer on both Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood and Donald Duck’s Playground.

Disney had no prior experience with computer games; the industry was barely a few years old, after all.

Not being sure how games fit into their structure, Disney assigned their educational department to act as liaison with Sierra. The department, whose usual work was in educational film strips and workbooks for schools, was not a good fit and struggled to understand what Sierra was creating.

“They had these two former elementary school teachers who had no clue what a computer was and they were assigned as our liaisons. Everything we did went through them,” Al says.

Both Mickey’s Space Adventure and the unreleased Goofy Word Game became bogged down in the interactions between the production team and their Disney liaisons. The team would show their updates for approval and would return with a new list of changes required.

|

Mickey's Space Adventure |

As composer on Mickey’s Space Adventure, Lowe watched the process unfold. “They wouldn’t make improvements or have even good suggestions. They would just say, ‘do this differently or make this a different color.’ It was just so that they had some input into the development process. Basically, it wasted our time.”

It was during the production of Mickey’s Space Adventure that the production team encountered Disney’s protectiveness of their properties – in this case their most valuable asset, Mickey Mouse.

Sierra’s first producer, Guruka Singh Khalsa, recalls the original opening scene to the game: “In the opening scene Mickey comes in and he stops mid-screen, he turns his head and looks at the player, pauses and taps his foot before he goes to walk across the screen.”

It was here that one of the production team had inserted a joke, hoping to amuse his teammates. At that moment if you typed in ‘Look at Mickey’ the game would respond with a coarse joke at the character’s expense. Unfortunately, the joke was left in and got through QA (Quality Assurance) to the Disney representatives.

“The game goes through QA and we get a letter back on Disney letterhead which has a gold magic castle at the top and everything. It’s from the Disney lawyers. It says, basically, you may not use the following words in a Disney product,” before listing out in three columns all the profanities that couldn’t be used.

That wasn’t a problem for Roberta Williams, designer on Mickey’s Space Adventure and co-founder of Sierra with her husband Ken, who wasn’t impressed by the team’s oversight. “Roberta didn’t like that sort of thing in her games. Disney was really her inspiration in her early games,” Guruka says.

When it came to designing Winnie the Pooh, Al worked on his design by reading all the Pooh books and synthesizing what he could. He then created a map of the Hundred Acre Wood, the setting for the Winnie the Pooh tales, and worked out the story and puzzles for the game. Then he decided to take a different tack in working with Disney’s liaisons. “I just went ahead and did the entire Winnie the Pooh game, got it finished and then showed it to them,” he recalls.

|

Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood

|

“They said ‘Can you change this or can you do that?’ and I replied that if we did that it’s going to get behind and I have other projects that I have booked ahead, so I don’t know how. I just kind of rammed it through; I did an end-around them and scored. I knew I had Ken’s (Williams) ear and I knew Ken would support me on it because he was interested in shipping the game and selling copies. He wasn’t interested in futzing around with this guy’s shirt color and that person’s feet color and stuff.”

“I basically said ‘Here it is, wanna sell it?’ So they did. They took the money.”

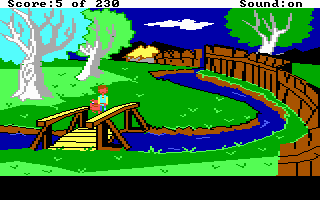

It worked. Disney were so happy with the success of the three games that they offered Sierra the opportunity to create a game based on their new animated movie, The Black Cauldron.

Lowe again agreed to design the game, this time with Roberta Williams, and accepted an offer from Disney to visit their studios and view an early cut of the film.

Seated in a private theater by himself, Al was impressed with the movie and could envisage creating a game based on it. “I got to see The Black Cauldron when it was the midst of production. Parts of the scenes were gorgeous finished and finalized stuff. Parts of it were pencil sketches. Parts of it were just a backdrop hanging on a piece of pipe in a basement. Literally you could see the pipe and a piece of wall and they zoomed in on it because it was going to get replaced with the final product. They would pick classical or some other sort of music and play a record behind it. The dialog was all in, though. So I got to see the film ahead of time and I said ‘Yeah, I can work on this.’”

After watching the movie, Lowe was sent to the archives, expecting to see something grand and opulent like the national archives in Washington DC. Instead he went down a set of exterior stairs to a door where he rang the doorbell and was led into a basement hallway by the archivist.

Al recalls, “As I stepped inside she said ‘Oh hang on, the phone’s ringing and there’s nobody else here. I’ll go get it, just wait here.’ So I stood in the doorway there waiting to start our conversation, and leaned my hand against the wall. I looked over and my hand was on the original pencil drawings for Sleeping Beauty. I was like ‘Oh my God! Seriously?’”

|

Sierra's The Black Cauldron |

In this basement hallway, with sewer pipes, water lines and sprinklers overhead, sat open industrial shelving with original drawings for every movie from Mickey Mouse’s first cartoon, Steamboat Willie. With no protection other than manila folders, the pencil drawings were stored on a steel shelf, so it was an easy process getting access to The Black Cauldron’s to take back to the production team for use in the game. Al took away copies of Elmer Bernstein’s original score and some pieces of background art.

Lowe also remembers his great surprise when he was taken to a gigantic mound of poster boards, each with an original background watercolor from The Black Cauldron. “They were just thrown in a giant heap and I said, ‘So, what’s with this?’ and she said ‘I have to go through this and decide which ones to keep.’ I said ‘You don’t keep them all?’ and she replied ‘Oh no! We’ll throw 98% of this in the garbage.’

“That was my introduction to Disney. But working on The Black Cauldron was fun. It was a fun project. There was very little oversight from anybody down there. We pretty much made the game that we wanted to and it was a really fun project to do.”

Still working at a reduced scale after the video game crash, the team worked out of the study at Ken and Roberta’s house. A large, relatively empty room, it had a shelf which sat about desk height and ran for close to 30 feet around the room.

“We just all kind of moved in there and worked on that shelf. That became our desks. We sat in his house every day and night. Because I lived down at Fresno, he just gave me a guest room at his house. I’d work until I couldn’t stay awake anymore and I’d go and have a lie down upstairs and come back and do it again. That was how we wrote that game!” Al says.

Al’s team, which included Ken Williams, Mark Crowe and Scott Murphy, worked hard to keep each other’s spirits up. Crowe and Murphy also discovered they were both science fiction fans, and while working on The Black Cauldron developed what became Space Quest, another major series for Sierra.

While The Black Cauldron marked the end of Sierra’s relationship with Disney, with Sierra moving on to concentrate on their own properties and Disney developing their own computer games, Al Lowe still has a reminder of those days on his home office wall.

“I ended up becoming a big Lloyd Alexander fan. He’s the guy who wrote the Chronicles of Prydain; they’re five kind of youth novels I suppose you’d call them. But boy, they’re really good books and good writing. One of my favorite things on the wall here, I have a signed letter from Lloyd Alexander talking about how much his nieces and nephews enjoyed my game. Pretty cool.”

Graphic adventure games. The name itself establishes how integral visuals are to the gaming experience. When Sierra started with Mystery House, backgrounds were crude and animations were non-existent, but through the years, they developed games that ranged from four colours to 16-bit colour, full motion video to pre-rendered 3D, and animation styles that ran the gamut from simplistic to Disney-esque. Next time, we'll explore Sierra's rich graphical odyssey that kept the company at the industry forefront throughout its heyday.