A Sierra Retrospective: Part 2 - Composing a Quest page 2

A Sierra Retrospective

A lookback at legendary game companies or series

The philosopher Plato once said about music that “It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, and flight to the imagination.” It was this flight to the imagination that was most relevant to Sierra’s adventure games.

Sierra had an unrivaled music department that produced many groundbreaking adventure game soundtracks during the ‘80s and ‘90s. “The level of talent they had within the music department was just unbelievable,” says Robert Holmes, composer on the Gabriel Knight series. “All of these guys in the music department, they were really, really, really good. There just wasn’t a slacker in the entire group.”

He says that working with such a talented group of musicians helped to bring everybody’s work up to a higher standard.

“The way Sierra would work was once a quarter there would be a company meeting and everyone would show off a demo or something that was part of their current project. You knew at some point your music was going to be shown as part of that to the whole company, so you really wanted it to be good.”

While music was certainly seen as a vital ingredient in the game design process, the composers and music team were usually brought in towards the end of production. Ken Allen, composer on many Sierra titles including King's Quest V, The Colonel's Bequest and Space Quest IV, says that “Music is often an afterthought in games, so I've been brought into the project late in the process. I have heard of some games where the music was chosen at the beginning and the game was designed around that, but those tend to be games out of Japan.”

Once a composer had been brought onto a game, they would meet with the designer to get a feel for the project and what the designer had in mind for the music.

|

Mark Seibert |

Mark Seibert was Sierra’s first staff musician and composed the soundtracks for games like Quest for Glory I, Conquests of Camelot and King’s Quest V. He explains that when he was first hired there was no design format for building a game soundtrack, so developing that system was an early priority. “Since we were making adventure games, I approached it like scoring a movie. Yes, of course the order in which things happen might be different, and the lengths of each scene might change (or even some of the story elements might be slightly different), but in general we could break it down into a series of events like a story or a movie. So that’s where I started with the designers,” he says. “Creating this framework helped us understand the big story arcs, and I think it also helped our designers to see their design in a new and different way.”

Ken Allen explains that as well as understanding the story arc, the composer also needed to get an understanding of what the designer was looking for. “I talked with the designers to get a feel for the musical style they imagined, and to see if they had any preconceived ideas for the music in cutscenes, or if they wanted characters to each have a theme,” Ken says. “I was looking for the psychology everywhere music is needed.”

While working through the game design document looking for the musical cues required – a process called spotting – the composer would also listen to music the designer liked or felt was similar to what they envisioned for a particular scene. This process helped to clarify for the composer what the designer wanted and why they felt a particular style of music would be appropriate.

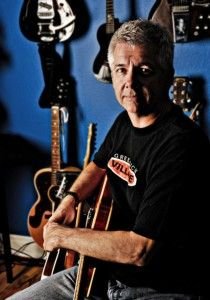

|

Ken Allen |

Using the information gathered from this spotting process, the composer would then start to develop concept pieces. While sometimes they might have the luxury of a fully designed game with a script for inspiration, it was usually sketches, storyboards or scene descriptions.

Allen says he would work on proof of concept pieces to make sure everyone was on the same page, while also choosing instrumentation based on emotions the designer wanted to evoke.

“If we decided on a certain musical style, the instruments I select would support that decision.”

The process was a little different for Robert Holmes when he composed the soundtrack for the first Gabriel Knight game. Holmes and designer Jane Jensen had become romantically involved prior to working together on Gabriel Knight, so in a rare situation, Holmes was part of the process from the very beginning.

Together, they would take daily walks around Bass Lake in Sierra National Forest and talk about ideas and how Jensen envisioned the series.

“We both watched movies together and talked about various influences, so I had a pretty good sense of what she was attracted to and what she was trying to achieve. And I brought my film music education to the problem and thought about what some of the guys I respected in the film world would do,” Robert says. “I think what I was trying to do was make music that was darker, more dramatic, and a little more emotional than had been done in games.”

Composing music for Sierra’s early games was also a different process for each system that the company released on.

Music in games today is generally a digital creature. An MP3 of your favorite artist could be a recording of drums, guitar and keyboards. These instruments are recorded on separate tracks which are then mixed together, or layered over each other, to form a complete song. A game soundtrack is created in the same way.

Turn back the clock to the 1980s, however, and the situation was vastly different.

Before the PC became the dominant home computer system, Sierra published its games in a wide variety of formats, the most common being the IBM PC, the Tandy 1000, and the Apple IIgs. As each system had its own technology which wasn’t compatible with the other systems, every game soundtrack had to be recreated for each.

The PC speaker in most IBM-compatible computers was only capable of playing a single beep which could be made to approximate different musical notes, as well as only playing a single track at a time. The Tandy 1000 copied the improvements IBM had developed in their short-lived PCjr system by allowing three tracks to be played at once, although these were still system-generated tones. The Apple IIgs was arguably the most advanced of the three systems, as it allowed for digital sampling of sounds to be recorded and played back. This allowed the composer to sample real instruments and compile those samples together to make a more layered and realistic sounding score.

(For a fuller appreciation of the differences, check out the Leisure Suit Larry themes on PC Speaker, Apple II and Tandy 1000 at designer Al Lowe’s website.)

By the mid-‘80s, sound technology had further developed with the advent of MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), which allowed a composer to store commands in a very small file format. These files weren’t music files like an MP3, but rather a collection of commands that directed a computer’s sound card to play a certain sound at a certain speed for the specified amount of time. The most common MIDI cards at the time were the Adlib and later the SoundBlaster.

|

Robert Holmes |

In his first role at Sierra, Robert Holmes was tasked with making soundtrack conversions for different systems.

“I would do the conversions for [fellow Sierra composer] Dan [Kehler]'s stuff, which was a great way for me to learn the ropes and get into the technology. I spent the first few months just doing the Mac and SoundBlaster conversions.

“For me it was different because while I had had some exposure to MIDI I really wasn’t a keyboard player and I really wasn’t well versed in MIDI. It took a while for me to really get into that. I never really got to the same level as some of the other guys who were really amazing MIDI composers. It was a good education.”

Recently, Holmes had the opportunity to return to his original Gabriel Knight soundtrack for the 20th Anniversary Edition, an opportunity not many game composers get.

“There were parts of it that I still like, and actually it was really interesting to listen to. I hadn’t heard some of it in quite a while. I was actually really pleased with some of it and thought, gee, if I had to play that right now I wouldn’t know how to play it,” he says. “A lot of it, in having to go back and review it, I would think, well, I would probably make a different decision now. It’s really tricky when you do something like that, because on one hand people expect something different, because that’s what they’re paying for. But on the other hand they don’t want you to mess with what they love. It was a really big challenge but also a lot of fun.”

The biggest advance in MIDI for Sierra was the adoption of the Roland MT-32 Sound Module, a hardware peripheral that generated ten MIDI tracks simultaneously. Sierra supported this module, which they believed offered the best listening experience for their games, selling it through their mail order system with an incentive offer of two free games.

While CEO and company founder Ken Williams was a strong advocate for the MT-32, the cost of the device (over $500) was a concern for some of the staff at Sierra, as producer Guruka Singh Khalsa recalls.

“I remember Ken being so excited about the Roland because MIDI was so compact. It didn’t take any space on disk to do MIDI code and the sounds were generated by the Roland box. I said to him people aren’t going to spend several hundred dollars on a MIDI box and he said, ‘We’ll include it with every game!’”

Williams wasn’t serious, of course, but the conversation does show the importance Sierra placed on their music. Through the technological changes from PC speaker to MIDI, and later to digital music, a game’s soundtrack was always seen as a vital ingredient in the adventure game process, allowing players to be immersed in the latest Sierra adventure.

While it’s common knowledge that LucasArts is now owned by the Disney corporation, it was Sierra who developed the early Disney computer games. Producing a line of children’s adventure games and a movie tie-in, Sierra was at the front of Disney’s early moves into the computer game market. In our next article, we’ll take a closer look at this relationship between the two prominent giants in their respective industries.