Review for PataNoir

Note: Since time of writing, this game has been ported to PC. This review is based on the original iOS version.

What if you could manipulate similes? When someone has a scar “like a canyon in the middle of an otherwise pristine African savanna,” what if you could enter that canyon? This is the central mechanic of PataNoir, an amusing but quite flawed little piece of interactive fiction by Simon Christiansen.

Now updated and released for iOS and Android, PataNoir was originally an entry in the 2011 annual Interactive Fiction Competition, where it came a respectable fifth place. The plot of the game is simple: you play a private detective hired to investigate the whereabouts of a Baron's daughter using your unique ability to affect similes. The story itself is forgettable, but this is unimportant, as it is more a playground for the game's central concept.

And what a novel concept it is. At first it's like any other text adventure: you start off in a room – in this case your office – with a paragraph or two describing it. But somewhere in the description a few similes will catch your eye. Shadows cover the floor “like dark pools of oil”; a wheel on your chair is covered in rust “like coagulated blood”. At this point you can interact with the oil and the blood just as easily as you can the shadows or wheel. Objects are divided into two types: literal and figurative (in others words, real and metaphorical). A figurative knife, for example, cannot cut a literal object, but it can cut a figurative object or, more interestingly, modify a literal object. Using the knife on, say, a person, might make their eyesight as sharp as a knife, or might make their attitude as pointed as a knife.

Though the premise is fantastic, the puzzles can be less than satisfying. The game follows a semi-linear progression, so you can explore the various locations and maybe work on a handful of objectives at a time, but eventually the obstacles bottleneck at puzzles that are very much of the read-the-author's mind variety, where the solutions only really make sense after the fact. This is partly due to the game's very puzzle mechanic, which naturally lends itself to abstractness and confusion.

Many puzzles are great challenges in their general wackiness, with plenty of inventive similes to explore. You go into the garden and find “strands [that] are all exactly alike, like citizens in a socialist utopia,” and guess what: you are then able to interact with these imaginary homogenous folk. When you see a sentence such as, “the table is covered with a diverse variety of empty liquor bottles, rising from the surface like minarets in a dilapidated middle eastern city,” it's easy to get excited at the possibilities. But sometimes the puzzles are just too wacky. You might need to somehow wake a giant in order to get a light source which you can use to swim to the bottom of a figurative ocean. Or you'll have to cure a fever-stricken man in order to make a room more "friendly". These sound like quirky ideas, perhaps, but if you go without hints or a walkthrough the solutions seem painfully unobvious and weird.

To alleviate the problem you are given a gun. No, don't get any ideas: you won't be shooting your way through this adventure. But thanks to the gun's description – "like a trusty servant never leaving your side" – it is transformed into a servant-cum-sidekick, Mr. Smith Wesson (named, of course, after the famed gun manufacturer). He is essentially the game's hint system; each time you type his name he will suggest a hint for your current location, in tiered levels. The trouble is, you’ll come to rely upon Wesson for all the puzzles that are particularly obtuse. And what's worse, he is little fun to interact with. He has no personality, no charm, no wit – he is little more than a hint command, only occasionally being used in aid of a puzzle. If he were more of an actual sidekick, the game could have created a back-and-forth of ideas between two minds trying to solve a case. As it is, Wesson feels so much more mechanical than personable.

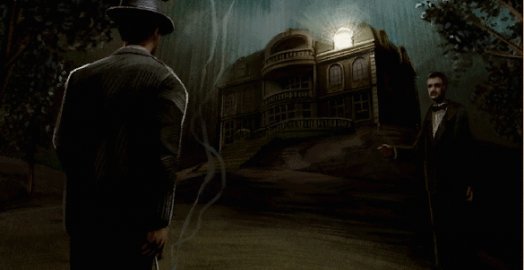

Thankfully, the game itself has much more personality than Wesson. Christiansen has joyfully employed various noir cliches, from melodramatic, sulking prose to decrepit nicotine-laden offices to a gritty, slightly unstable detective. I'll admit to some occasional eye-rolling ("the air is cold and clear, like the justice we all seek but never find") but mostly I found the writing entertaining. You also get accompanying illustrations of various rooms that unlock as you play, which are all wonderfully broody and over-the-top. Even better, there's a spectacularly cheesy (and admittedly quite catchy) theme song with an idiosyncratic saxophone sound wailing out the melody alongside female vocals. The heavy stylisation generally holds the game together, and makes it easier to overlook many of its flaws.

Apart from the illustrations and song, the game still uses a standard text adventure interface. You have the parser at the bottom, the text above, and a few typographical options to choose from. The only visual difference, using the interface Andrew Plotkin invented for games like Hadean Lands, is that there is a menu bar at the bottom. Here you can make notes if you want to, browse through the “info” page where you'll find the instructions, artwork, song and walkthrough, and adjust the settings.

More specifically to PataNoir, there have been some handy parser modifications. You can, in many instances, eschew verbs altogether. Instead of typing >examine snakes you can just type >snakes and the game will print out a description. And if you type it a second time, the game will attempt the default action for that object, usually >take [object]. This is a useful addition not only to those new to Interactive Fiction, but also to veteran players: as descriptions are integral to PataNoir, it is a useful way to make sure you miss not a single one.

So PataNoir is a mixed bag. It's a terrific concept dulled by many poor puzzles, such that players will almost inevitably end up reliant on the in-game hint system. But thanks to the uniqueness of the game and the music and illustrations that come bundled with it, it is partially redeemed. If you're curious to try something distinctly different – particularly wordplay and noir fans – and think you can overlook its weaknesses, then you may get a lot out of PataNoir. But I imagine most will come away, like me, feeling somewhat unsatisfied, having fallen eagerly in love with the premise only to be left disheartened by the result.