Review for Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward

Imagine two scenarios:

In scenario number one, you find yourself waking up kidnapped with eight other people you’ve never met. You soon discover that you’re taking part in some twisted, deadly game, and will likely be killed if you don’t play your cards right.

Scenario number two is the one in which you’ll find yourself playing a videogame version of the same life-and-death contest. The catch, however, is that to get anywhere, you must constantly restart the game from the last branching path to find slightly different outcomes and different pieces of the puzzle. And each time you do this, you have to listen to others talk and talk and talk—going on at length about something they could have better described in a single sentence.

While the first scenario definitely has promise, the second represents the gist of the last thirty hours I’ve spent tapping my way through text in Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward on the PlayStation Vita. This is a game theoretically about making fast, important decisions to avoid death, yet it’s one of the slowest and most overwritten adventure games I’ve played. If this sounds at all familiar, you may have heard of its predecessor, 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors on the Nintendo DS. If you haven't, you're not really missing anything integral to the sequel. There are some reappearing themes and characters, but the only real benefit to playing the original game first is some extra fan service.

Remember the “choose your own adventure” books that appealed to you as a child? If you reached a dead end but weren't happy with the treasure you found, no worries—simply try, try again! As an adult fan of video games and horror, however, this choose-whatever-you-want strategy does little to add tension in what should be (for all intents and purposes) a suspenseful game. Once you find an ending (good or bad), you’re given a narrative tree where you can simply head back to the point where you branched off to try something new. The result is a story with nothing really at stake, and it only takes a tap on the touch screen to try for a more inviting ending.

Granted, once you see a few endings, you’ll definitely be involved—you’ll learn far more about the characters and their motivations, adding some enlightening perspective. But it’s a slow churn. The game doesn’t give you any initial reason to care about the characters or what’s at stake for them, and if you happen to get one of the “wrong” endings the first few times through—where there’s no big reveal—then you might find yourself indifferent to the game’s suggestion to slog through it again. My first ending involved seeing others die as I died myself, and I hadn’t learned anything compelling about the characters at that point.

Of course, this is a game, so it does let you play occasionally too. It’s not quite as interactive as your typical adventure game, though, with distinct separations into “Novel” and “Escape” (puzzle) sections. And the “Novel” portion is where you’ll be spending the majority of your time. While the story does contain an occasional choice on your part, keep in mind that you’re in for a lot of reading, and like it or not, you may have to tap/button-press your way through half an hour of text before getting to any decision-making on your part.

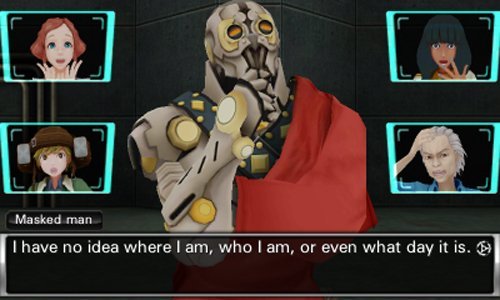

It all begins when a young university student named Sigma wakes up in a warehouse, along with eight other edgy, upset, and bewildered guests. You're soon informed by an A.I. rabbit (with an obnoxious gameshow voice and some sort of A.I. multiple-personality disorder) that someone named Zero has brought you here to play the “Nonary Game: Ambidex Edition.” In this game, everyone has a watch they cannot remove. Each character’s watch has a certain number of points displayed; if the number reaches zero, the watch will shoot needles into the wearer, releasing drugs to swiftly kill them. Anyone whose number reaches nine can exit through a large door, along with any others fortunate enough to survive to that point. The door can only be opened that one time, however, so depending on who makes it in the end, the remaining characters are stuck in the warehouse, seemingly forever.

One particular thought experiment—The Prisoner’s Dilemma—is what drives the point totals in this twisted game. In case you’re not familiar with it, this dilemma basically boils down to the question: Do you betray your partner to make things easier for yourself? Sometimes the rational choice isn’t clear. In Virtue’s Last Reward, you go into a voting room to make “ally” or “betray” votes with the people you are currently trapped with. After escape rooms are explored, you’ll find yourself back in that voting room again, seeing who’s up next to be penalized or rewarded.

It’s never really clear whether allying or betraying is the “right” thing, or if it’s something that eventually will lead to a “real” ending. For example, you gain the most points for choosing to betray if the other party chooses to ally (a total of three points for you, while the opponent loses two), but you also get a decent amount for allying (two points) if the other character decides to ally as well. There are other pairings that lead to different amounts of points, and it all boils down to silly, overwrought conversations of "I chose betray because I thought you were going to choose betray", etc. In the end, it feels like a game much more about strategy (or guesswork, at times) than ethics. Most of the time I felt it made no difference if I just opted to choose something random.

And unfortunately, these votes aren’t as tense as they could be—by the time characters stop yapping about whatever choice you should or shouldn’t make, you’re not very likely to care anymore. The game is timed, but only for the characters. Meaning, you’ll continually listen to lengthy conversations about how everyone is running out of time, while you sit idly by wishing the game actually felt like it.

It’s a pretty varied group, at least: within the nine, there’s an excitable child named Quark with a ridiculous hat; the mysterious Phi, who seems smart and trustworthy yet won’t tell you anything; and the enigmatic “K,” a thoughtful, collected man with bizarre all-body armor and no recollection of who he is. Naturally, these characters don’t really trust one another. At least not at first. There are times when people decide to split up or band together, but most of the time it feels like they’re bickering or running off to find someone who’s gone missing (this happens a lot).

There are some twists and surprises, many of which you will not see coming. If you think you have an idea of who the host is, how the game is going to play out, or who the characters really are, you’re in for a fun surprise. And while all the little anecdotes and found objects may seem like red herrings at the time, you can expect every bit to fall into place somewhere in the story. Still, the overall tone of the game feels a little like the campy horror classic House on Haunted Hill with Vincent Price, but more sci-fi and more mathematical, with a lot of talk about antimatter, lunar eclipses and thought experiments.

Given the amount of talking, thankfully the voice acting is serviceable, though expect some cheesy overacting. Except from the protagonist, a silent persona who isn’t given the voiceover treatment, presumably to allow easier character identification for the player. Sigma, however, is very much a personality all his own anyway—he’s irritable, perverted, and likes to make cat puns. When so many of the game’s conversations involve him, it kills the flow of dialogue to hear one side and read the other most of the time. For an interesting change of pace, there's a great option to choose the original Japanese voices for the other characters (with English subtitles) every time you load up a save.

The game’s best dialogue comes near the end of each character’s story, which explains their fascinating origins. These thoughtful tales border on moving, but there’s little reason to care about the characters until then. For hours leading up to these grand finales, they haven’t been developing in any way that would make their lives interesting to you. They’re too busy either getting annoyed or making jokes at the expense of other characters. The latter creates quite the tonal dissonance. When you hear Clover—a strong, serious female character—giggle several times about how she thought a room labeled “pantry” said “panty,” you’ll wonder why all characters seem to share the exact same (read: the author’s) proclivities for potty humor and puns, particularly under such supposedly desperate circumstances.

To get through the massive amounts of dialogue, the game has three options: Stop, Skip, and Auto. The skip function lets you fast-forward sections you’ve already seen; the auto function progresses the story at its own pace so you can sit back and enjoy it; and stop allows the less patient to breeze through text by pressing a button or tapping the screen.

In between all the reading is a series of escape-the-room puzzle sequences. Unlike the narrative-based portions, where the lack of graphical fidelity is made up for with storytelling, these environments do little for the imagination. As you move your way through infirmaries, pantries, gardens, and medical labs, there’s very little aside from the occasional quip from a character to draw you into the scenery. On the Vita, you can navigate these barren, sterile 3D environments using the analog stick or touch screen. I found the touch screen much more efficient and responsive. Using the stick means pushing a cursor all the way to the right or left to simply look at a different part of the room; with the touch screen it’s a simple swipe. You can also use the touch screen to see a 360-degree view of the items you collect, which can be used and combined with other objects.

These "Escape" sections all involve a larger puzzle with several minigame challenges within. Unfortunately, they’re relatively uninspired in their variety. You’ll encounter a handful of slider puzzles, a good number of measurement and scale-sliding puzzles, and quite a few word problems involving a simple elimination process with the information you have. I wouldn’t describe many of these puzzles as very fun or engaging, but they do at least tie in with the themes of science and the game’s heavy-handed approach to explaining its topics by detailing mathematical formulas and processes. When solving puzzles, you won’t need a solid understanding of mathematics, but you will perhaps like a calculator nearby. It also might be a good time to switch to analog controls if you’re using the touch screen—I kept accidentally selecting and rotating the wrong blocks in one puzzle.

Puzzle-solving is made more frustrating with the clumsy “memo” function, which gives you two screens to jot down info as needed in several different colors. Great idea in theory, but the small Vita touchscreen (lacking a stylus) makes for difficult entry, especially considering the bulk of the puzzles require you to remember patterns of numbers and letters. Even with my small hands, I found myself erasing and writing over and over. Alternatively, you can use the Vita's screenshot functionality to just take a picture of the area, but this requires accessing a separate application on the Vita just to see it.

Once you complete one of these rooms, you’re given a safe key to exit, though you might want to search for the optional secret file before you leave. These dossiers contain interesting facts about the game, secrets about the characters, and personal details about the author (randomly, one of these documents describes his fetish for swimsuits). If you have trouble in any of these escape rooms, not to worry—there’s an easy mode available at any time that offers more hints. Once you make the change you can’t switch back to hard mode, but the only penalty for choosing it is a loss of some of the non-essential file info.

Outside of the escape rooms, the characters occasionally work through dilemmas on their own, but if you’re a fan of recent decision- and character-based games such as The Walking Dead, you’re likely to be disappointed here. Instead of featuring poignant, urgent decisions involving life-and-death, Virtue’s Last Reward ruins the immediacy by forcing you to sit through these discussions of algorithms and minutiae. You simply watch the characters hem and haw about the decisions they’re making, then in the end you merely select options they’ve come up with from a menu. For example, early on the group is told that they can only enter specific chromatic doors that match the information on their watches. The game pulls up a Venn diagram, has the characters hash it out for ten minutes or so, and then essentially brings things back to you to say, "alright then, okay". It’s like being forced to watch a PowerPoint presentation at a meeting that doesn’t apply to you.

Still, this game is far less tedious to play through multiple times than its predecessor. A replay tree makes it much more intuitive this time around to jump to that last wrong turn, with a clear delineation of different routes you can try. And if you do play this game, you'll want to make sure to keep replaying it. After reaching one of the game’s major endings, it gives you a unique perspective on the motivations and feelings of some of the characters, giving you renewed incentive to find out more. The choices of “ally” or “betray” continue to feel pointless, but the final endings add a lot of story content and help create much-needed empathy for your fellow captives. Unlike in 999, you don't have to start over each time—you’re simply selecting a spot where you want to try something different. This doesn’t make the game’s exposition less tedious, of course, but it does make for quicker playthroughs.

The intro to Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward asks you the question: Why do people betray each other? The game succeeds in addressing and answering this query, but you’ll need to wait quite a while to find out. If you don’t have the time or patience for this dialogue-bloated yet intriguing mystery, you may find yourself betrayed (or at least bored) by the tedious chatting and rote puzzles. But if you do, you’re in for a reasonably rewarding experience, one ending at a time.

_capsule_fog__medium.png)