Jan Kavan – J.U.L.I.A. interview - page 2

Calling a game a great indie endeavour may sound like damning it with faint praise. After all, independent productions are invariably low budget affairs that have a tough time competing with deeper-pocketed studios (though that’s a fairly relative term in the adventure genre). The implication is, lower your standards for an indie game and it may just clear the bar. But it can mean much more than that, as being an indie also has some inherent benefits. You can take chances no publisher would endorse, and go in a more artistic, personal direction without bowing to safer commercial pressures. That freedom can lead to some really creative, inspired productions we’d never see if not for the independent status of their developers.

J.U.L.I.A. is a great indie endeavour for all the right reasons. This unique sci-fi adventure from the two-man Czech studio Cardboard Box Entertainment doesn’t do anything “new” so much as it packages its diverse elements in clever, interesting ways, combining to form an experience that feels quite unlike any other game. It also embraces its own limitations, opting for a slick but fairly spartan presentation that suits its indie sensibilities. If the text adventure had evolved along completely different lines instead of turning into the modern day graphic point-and-clicker, it might look a little something like J.U.L.I.A.. Intrigued yet? Well read on, as I recently had the chance to play through a late-beta version of the game, and came away duly impressed with what I saw. This isn’t a promising adventure “for an indie”… it’s a promising adventure that could only be an indie.

Don’t misunderstand the text adventure comment: J.U.L.I.A. does have graphics, and it’s controlled almost exclusively with the mouse. But unlike most adventures, it doesn’t rely on those things to deliver its story in a compelling way. This is a far more cerebral experience that favours suggestion over depiction, showing you just enough to draw you in, then letting the dialogue, gameplay, and your own imagination do the rest. In fact, CBE doesn’t even call it an adventure game, preferring the term “logical video game” to describe its highly streamlined, task-driven exploration. It may not be for everybody, but it’s certainly something everybody should check out.

Despite its distinctive approach, J.U.L.I.A.’s initial premise will sound fairly familiar to any science fiction fan. In the year 2430, astrobiologist Rachel Manners is awakened from cryo sleep by the titular A.I. controlling her interstellar probe when a meteor hits the ship. Repairing the craft is just the beginning of her adventure, however, as Rachel soon learns that not only is she alone, the rest of her crew abandoned the ship many decades earlier in pursuit of sentient life. Since J.U.L.I.A. claims that part of "her" memory was wiped in the process, the only way to discover what happened is by following Rachel’s (former) colleagues to the six nearby planets in search of clues – or more accurately, by monitoring the hulking mechanical Mobot do so through video feeds from afar.

When on the orbiting probe, you interact directly with the major ship functions, including planetary scanning and resource harvesting, Mobot upgrades, and ship repair. All are easily accessed through a navigation bar, opening up a sub-screen for each activity. Nanobot ship repair is done just once, performed by clicking and dragging the correct item onto the screen as you move on rails through an automated 3D tour of the ship. Timing is of the essence, but the allotment is reasonable, and you can’t actually fail, as you’ll circle around as often as necessary to get every object in place. There are three upgrades for Mobot achieved by completing a complex schematic form of Pipes. Resource harvesting is done for each planet you visit, and somewhat resembles the process in Mass Effect 2. Here you’ll be sweeping a scanned segment of the planet’s surface looking for matching graphs to pinpoint the resources you need, though as the cursor changes colour the nearer you are to a desired mineral, you’ll almost certainly spend more time watching the cursor than the graph.

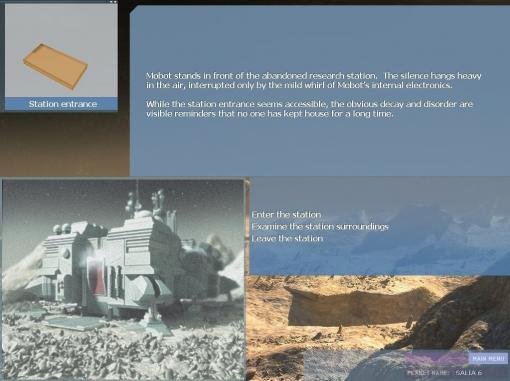

Played from a first-pers… I mean, first-artifi… wait, no, first-robo… well, first-something perspective, you’ll spend far more of your time on the planets below, shown only through grainy, noise-filtered images sent by Mobot. The screen is split into various window functions, including a mini-map, dialogue box, and photographic stills. This is more functional than visually attractive, but it’s nicely framed by technical displays and fits the storyline perfectly. You’re viewing new worlds through a machine’s eyes, and what "he" sees is what you get. Each planet allows some exploring, but not in the traditional way, as you won’t be clicking cursors or hotspots. One world has you navigating through an auto-mapping grid-based maze and another by following sonar through deep black waters, but most present a series of narrated text descriptions with response options to select. There are no right or wrong answers, and you’ll need to visit all areas eventually, but you’ll choose when to instruct Mobot to enter buildings, examine corpses, or access data logs.

You will collect items as you go, but there’s no visible inventory, as any objects you acquire simply become part of your text choices at the appropriate time. You’ll encounter quite a few other puzzles that are much more difficult to solve, however. Some are familiar but contextually disguised standalone types, like five-image tile jigsaws to restore damaged memory clusters, Lights Out cognitive worthiness tests, and misaligned chemical gauge balancing, while others need clues to complete, like codes for keypads and wire connection tips. A few are clearly contrived, but several are beautifully integrated, like descending your way through a block-tiered ice world and assembling a hi-tech energy weapon. A few are repeated, but never so often that they feel repetitive, though they do get progressively more difficult each time.

That’s important, because J.U.L.I.A. is not an easy game. But nor is it unfair. I almost keeled over at the sight of a numerical cipher, yet slowly but surely I pieced my way through the coded message. Despite its highly streamlined nature, this is no “casual” game with helpful hints and puzzle skip options, so you’re on your own to get through the challenges yourself. The only exception is a math-based puzzle that offers assistance before you begin. I chose yes, only to get a lot more help than I anticipated, leaving me mainly to input numbers already calculated ahead of time.

There’s one other minigame that requires a degree of dexterity, though it’s not an “action” sequence per se. I won’t spoil the context, except to say that it’s a fairly titanic confrontation that requires keeping a twitchy cursor centered on a small target. Failing simply means starting the sequence over, however, as there’s no fear of (permanent) dying or other game-over scenarios here. I thought this sequence would mark the game’s climactic challenge, but I was wrong, as J.U.L.I.A. proceeds to spin off into entirely new areas beyond the initial desert, ocean, jungle, and ice-covered worlds, ultimately culminating in a moral choice that impacts which of the two endings you experience.

It won’t be an easy choice, as you’ll discover some unpleasant truths in the troubling backstory of mankind’s first encounter with extra-terrestrials. The story isn’t particularly deep, but it does delve into ethical issues of self-preservation and justice, careful not to paint the issues in black-and-white, good vs. evil brushstrokes. You’ll glean some insight from your encounters with the same alien races (once you learn to communicate), and some through recorded documents left by the probe team who abandoned you. All the while, you’ll be accompanied by the cheerful voice of J.U.L.I.A., whose Data-like emotion chip makes her seem more human than artificial, and Mobot, the purely mechanical and yet surprisingly personable machine who seems all-too-aware that it’s his metallic hide that’s on the line in hazardous environments, not yours.

Each character is fully voice acted and quite well done, from Rachel’s pleasant English accent to her companions’ slightly modulated tones. Some lines seem to be poorly inflected, but as neither J.U.L.I.A. nor Mobot are human, that could very well be intentional (or at the very least, conveniently passed off as such). The music is as varied as the environments, shifting radically from gentle piano to Eastern strings; from tribal chants to more traditional 2001-like orchestrals, among others, providing a remarkably diverse aural backdrop to the action.

While it’s never necessary (or often possible) to finish a game played for preview, it speaks to the quality of J.U.L.I.A. that I felt compelled to see it through to the end. It’s certainly unlike anything I’ve ever played before, and although different doesn’t always mean better, it does make it noteworthy. Yet this game warrants your attention for more reasons than that. It’s got all the budgetary hallmarks of an independent adventure, sure, but the developers have smartly capitalized on those limitations in a way that’s actually a benefit. No one watched the Mars probe expecting to see Avatar, and the mystery of the Salia system is similarly enhanced by the teasingly detached view offered here. With plenty of challenging puzzles and a solid sci-fi storyline tying it all together, I suggest making room on your calendar for a date with J.U.L.I.A. this fall. In the meantime, in case you still can’t get enough, next up is a behind-the-scenes chat with the game’s writer and designer, Jan Kavan.

Adventure Gamers: Let’s start off with the basics: what the heck does J.U.L.I.A. stand for?

Jan Kavan: The acronym indeed has a story of its own. There are several similar stories which were not spelled out in the game, but rest assured that we’re currently cooking something. Stay tuned and you may find about this and other untold stories sooner than you’d expect. ![]()

AG: Hey, teasers are supposed to come at the end! Okay, first it was ghosts in sheets, now space exploration. That’s quite a thematic shift. Why the move to sci-fi for your second game?

Jan: Well, actually we started with Destinies, which was an old school sci-fi story. However, we were never able to secure proper funding for such an ambitious game, so after many years of trying, we decided to let it sleep for a while and do something smaller.

It was also some time after Jonathan (Boakes) made a breakthrough with his ghost-themed games and all of a sudden everyone was doing ghost-themed games. One day we were being silly and came up with the idea of reversing the role – that instead of the scary ghost-hunting game, we’d make a comedy about a ghost as a main protagonist. In the end it was a great learning project for us. We learned what it takes to finish and bring a video game to market without a single cent of funding.

So to get back to your question, I prefer sci-fi or fantasy themes, and as a writer I am more at home with serious, mature themes than with my specific pitch-black humor.

AG: Have you been a science fiction fan for a long time?

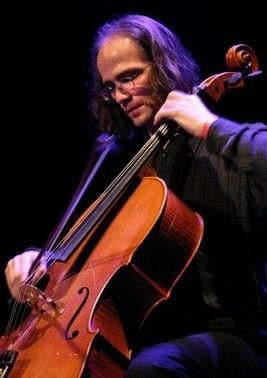

Jan: Yes. I’ve been an avid reader since the age of four, and I spent way more time in my early childhood reading sci-fi books than I did playing cello. ![]() This turned around when I started to attend the conservatory, but as a kid I read literally thousands of sci-fi books.

This turned around when I started to attend the conservatory, but as a kid I read literally thousands of sci-fi books.

While listing all the names which have influenced me would be an almost impossible task, I have to say that I always loved the work of Clifford Donald Simak and I guess it shows in J.U.L.I.A. as well as in the Destinies story. While both games are sci-fi themed, the technology is not the main point. My games will always be about “chamber” personal stories rather than some overly-constructed alternate universes with their epic story proportions.

AG: Genre isn’t the only thing that’s changed since Ghosts in the Sheet, as J.U.L.I.A. is a pretty major departure from tradition in terms of format, approach, gameplay, etc. as well. What inspired that decision?

Jan: I think it’s fair to say that you’ve actually played “J.U.L.I.A. 2”. More than two years ago we had “J.U.L.I.A. 1” finished, but we played through it and found out that it wasn’t a good game at all. So we threw literally everything into the dumpster and started from scratch. Nonetheless, by doing that early version of the game, I found the format I wanted to have for this kind of game.

Generally I don’t design a game by telling myself “I need to do a point-and-click adventure game”, but rather I ask myself if the gameplay will be fun and if it matches the story I want to tell. By iterating and fine-tuning the principles, I was able to come up with this format and approach to the game.

AG: You’ve seemed reluctant to actually refer to J.U.L.I.A. as an “adventure game”. Are you consciously avoiding that phrase for a reason?

Jan: The roots of J.U.L.I.A. are for me way older than graphic adventure games. I was a huge fan of IF (Interactive Fiction) games and played lots of them. I was very sad when they became such a niche genre. J.U.L.I.A. was for me a bow to those old IF games I used to play and love. A Mind Forever Voyaging, Trinity or Portal (the innovative interface-based game from 1986 by Ron Swiggart) comes to my mind, just to name a few.

I tried to revive the genre with the inclusion of visuals while maintaining the calm pacing and word-heavy nature of IF games.

Besides, if I call J.U.L.I.A. an adventure game, way too many gamers would immediately pigeonhole it as either 2.5D or a first-person slide show game. It’s neither of those so I’d rather accent the narrative-driven nature and omnipresent logical puzzles.

AG: The IF influence is something I picked up on right away when playing. Were you purposely looking to defy point-and-click convention to be different, or did your approach to J.U.L.I.A. just emerge naturally as you designed it?

Jan: If I had a huge budget, J.U.L.I.A. would have all the planets fully explorable in an awesome, effect-packed 3D. You’d have to steer Mobot down to the surface, navigate it around and solve the very same puzzles but in the context of a living, breathing place. Obviously, this was not the case. So I had to decide – do some half-baked 3D which would look bad and drive off players immediately or try to use human imagination as the most potent weapon. I did the latter and here we are again – back to the theme of IF games.

AG: J.U.L.I.A. seems suited to casual game players in terms of its fairly streamlined approach and puzzle-centric gameplay, and yet this game comes with none of the standard casual conveniences. Aren’t you limiting your potential audience by not making the game a bit more accessible?

Jan: This was one of the more difficult decisions. The main point which tipped the scales in favor of not doing so was that having a logical game and offering puzzle skips and hint systems could turn the game into a clickable “YouTube” video. Certainly there will be walkthroughs available but from my experience, as soon as you build a hint system, players will use it immediately when they’re stuck because they want to get on with the story. Eventually this creates those “too short – I finished the game in less than 35 minutes” complaints.

So even though I was responsible for the hint system in the later Carol Reed games and it would have been super easy for me to implement one in J.U.L.I.A., I decided I wanted to keep that old school aura the game has now.

AG: This game is almost entirely a two-man production between you and Lukáš Medek, which is pretty remarkable. What are the biggest challenges you face in doing everything yourselves?

Jan: Splitting time for work, game development, families and keeping our sanity intact. ![]()

AG: Is this a full time job for you both, or do you try to fit in development time between work that actually puts food on the table?

Jan: For me it’s night work. I am regularly employed and have to pay the family bills. Lukáš is still studying so his condition is slightly better. We currently operate on my “kitchen budget”, which means that I pay the bills for everything J.U.L.I.A.-related. This gives me the freedom to come out with the game when I see fit since I don’t owe any money to anyone else.

And fortunately I have a very supportive family which tolerates my whims. For now, that is… ![]()

AG: Your background is in music, correct? How did you come to be involved in making games?

|

Jan Kavan |

Jan: That’s correct. I studied cello at the Conservatory and later pursued my musical studies at JAMU (Janacek’s Academy of Performing Arts) as a composer. However, my first video game was for C64 and I made it when I was 15 or so. Back then I knew more about C64 then I’ll ever know about current generation PC’s. I was very fluent in assembler and later continued with Pascal, C, C++, C# and other languages.

The main driving vehicle for learning how to program was the burning desire to create computer games. Looking back, it’s a long-lasting obsession which paid off since I can now make my living as a programmer.

AG: Given your penchant for diversity, can we expect a musical comedy from CBE next?

Jan: You’ve almost hit the nail on the head. Some time ago we teamed up with a great L.A. based composer, Martin Herman, who has an incredible idea for a game, which in my opinion may shift the general view of what an adventure game actually is and how it interacts with a player. Without disclosing anything, we’re really excited about this project and it goes without saying that the music and sound will play a major if not critical role there. It will be very far from a comedy though.

However, this game requires switching to a brand new technology. We’ve found out that we’re not ready for that and right now we’re pursuing two new small scale games. One has been outlined in this interview already; the other will be announced during the next year.

And there is always Destinies. We never gave up on the game and if we one day get funding for a decent team, it’ll be our priority. Way too much work went into that game.

AG: In the meantime, when can we expect to see J.U.L.I.A. released publicly, and where should we look to buy it once it’s launched?

Jan: Generally, we’re targeting Q3 or Q4 release. We are certainly hoping that after Gamescom, we can be much more concrete. For now, please watch our site for the news.

AG: Glad to hear it’s soon, because I really believe people are going to be impressed. Jan, thanks so much taking a few moments out of crunch time to chat with us… Now back to work!