Review for Lux-Pain

Lux-Pain: a divine or holy pain.

In the internal parlance of this utterly bizarre new Nintendo DS game, the above is merely the definition of its title. Unfortunately, to make a long story short, it’s also pretty much what players will be feeling well before the end of this peculiar interactive experience. The reasons for this add up over time, primarily because Lux-Pain is so intent on making its own short story REALLY long, and forgetting to include much in the way of a game to make the increasingly tiresome narrative worth following through to its conclusion.

It’s a bit of a headache just trying to describe what this game actually is. Its own marketing materials refer to it as a “text-based adventure”, but while it certainly has a heck of a lot of text, it has practically no adventuring at all, by any meaning of the word. With only two simple minigames endlessly interjected throughout, really it’s little more than an interactive visual novel, and often a rambling, overly obtuse, shockingly non-sensical one at that. Lux-Pain, then, is not an adventure and not very good, but it is definitely weird and very, very Japanese.

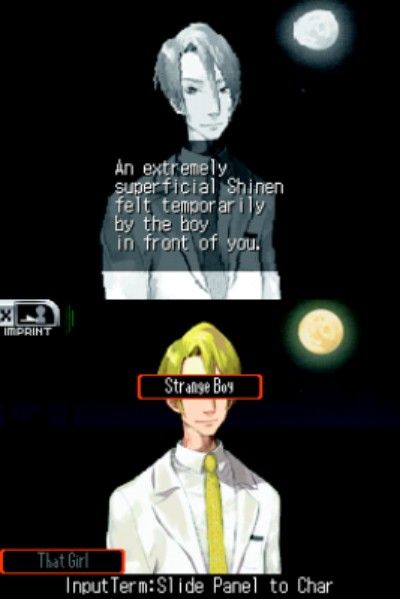

The discomfort grows in attempting to grasp what the main storyline is about. Players are cast as 17-year-old Atsuki Saijo, one of the rare people with the power of Sigma, an ability to both read and manipulate people’s minds. A member of a secret group called FORT (Force for Obliteration of the Rising Terrors – thank goodness for acronyms), Atsuki arrives in Kisaragi City in pursuit of a dangerous Silent, a creature once commonly thought to be a demon but really a kind of mental parasite that infects people through their memories and emotions. These “worms” leave their impressions through residual Shinen, which Atsuki can detect in people, animals, and even places. In Kisaragi, Silent is causing an alarming number of disturbing events, from simple mischief to animal abuse to suicide to murder, and believing the city may be home to the original Silent, FORT hopes to eradicate it at its source.

Everybody got all that? I’ve left out a bunch of other terminology like psycho viewing, imprinting, zone ether, and term synthesis, as the verbiage quickly gets overwhelming, but thankfully all relevant information is available both in the detailed game manual and extremely comprehensive in-game database. Once you strip away all the fanciful lexicon, however, you’re left with a “read people’s minds, conquer invisible worms to stop evil” premise, which is potentially very interesting… and then you’re sent to high school.

Yes, instead of actually hunting down diabolical spirit mindjackers, you’ll spend much of your time chatting up your many classmates and teachers while “undercover” as a foreign exchange student. The game takes place over the course of three simulated weeks, during which time you’ll sit through pointless classes and endure more trivial social interaction than is remotely tolerable. This is meant to give depth to the game’s numerous supporting characters, and while it marginally succeeds in doing that, the approach is so haphazard and contrived that it offers nothing to the story. Many of the topics are simply inane to begin with, while even the moderately relevant ones are drawn out to the point of tedium. The game makes no attempt to hide the fact, either. I lost track of how many times someone would “stop” themselves (after carrying on at length, naturally) with a comment like, "What am I talking about? Sorry." or "I can’t stop talking when I’m with you." Then there’s my favourite, "We just met and I got all weird." Sadly, for someone with the ability to affect people’s minds, there’s no way to make them shut up.

The other main problem with the social element of Lux-Pain is that it’s so blatantly unrealistic, somewhat uncomfortably at times. One policeman refuses a little girl entry to a crime scene, not for any of the valid reasons you could name off the top of your head, but so that he wouldn’t get yelled at! Meanwhile, anyone and everyone will flirt with you constantly, men and women alike, student and teacher alike. Almost all the women in the game look like they’re about twelve years old, and they all act like it, too. An immature twelve, that is. Some of them even are twelve (or close to it), but that won’t stop at least two of them from insisting you take them on “dates”. The whole theme never actually goes anywhere, but that doesn’t stop the script from relentlessly chasing sexual tension in a kind of pre-teen Harlequin Romance kind of way. Strange. Awkward.

Most of the time you’re simply tapping through all these conversations with the stylus, though there is the occasional chance for interaction. A handful of times you can choose a response based on “mood” colours, while other times you simply select one of several possible answers. Generally you know if you’re offering positive or negative reinforcement, though it can be a little hard to tell, but it doesn’t seem to have much impact on the outcome. In a few instances you can actually present a topic from something resembling a dialogue tree, but only when prompted and the choices are always sparse. For the vast majority of time, you simply click your way through the nove… err, game.

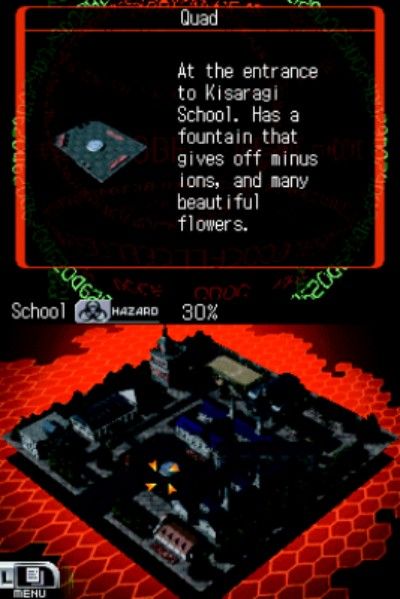

Once the final school bell rings each day, the game does pick up somewhat, but since you meet many of the same people everywhere you go, often it’s simply more of the same. It’s a huge cast overall, and over time you’ll likely begin to grow fond of some of them, like the budding journalist who’s a magnet for trouble, the kind-hearted fortuneteller, and a young girl who can speak to animals. You’ll also wonder why some were even included, like the local postmaster who’s obsessed with a small idol, the school nurse with no evident medical training, or the dimwitted Internet Cafe owner. To the game’s credit, it does finally arrive at some compelling if convoluted plot points, even bravely confronting the player with tragedy in different forms, but without exaggeration, the script could easily have been cut in half and been a tighter, better narrative. Never is this more apparent than the many emails you get (the most memorable was the one from a cop apologizing for the drunken ramblings of the last mail) or the chatroom transcripts (a conversation about cucumbers leaps to mind, but it’s only one example of far, far too many). It’s all meant to add optional colour, which is admirable, but it ends up coming off like so much white noise instead.

A script reduction would have cut down on the enormous number of translation issues and outright typographical errors as well. While most individual words and sentences make sense, often the context of a conversation seems to be almost random. It’s as if characters are engaged in stream-of-consciousness and verbalizing their thoughts as they go. I suppose it’s possible that’s what the writers intended, but presumably something’s been lost in the conversion from its original Japanese, as I’ve never engaged in a single dialogue that resembled anything like one of Lux-Pain’s. Speaking of translation, while the text is completely in English, all of the characters have Japanese names. Ignorant gaijin though I may be for saying so, this can make it difficult to keep track of who’s who: Atsuki, Natsuki, Yuzi, Yui, Rui, Ryo, Maki, Mako… you get the idea. Even that wouldn’t be so bad if the game didn’t keep switching to last names without warning. The first few times someone talked about “Saijo”, I didn’t even know they were talking about me.

The name issue is probably an accurate reflection of Japanese culture, but the characters neither look nor sound Japanese. That’s right: sound. Unlike most DS titles, Lux-Pain actually features a fair bit of voice acting. It still represents only a tiny fraction of its voluminous dialogue, but key exchanges are spoken aloud. With the exception of any actors portraying young girls (note to all directors everywhere: get kids to voice kids!), the vocal performances are very good. The one startling caveat, however, is that the spoken lines are often radically different from the text being displayed. I don’t mean small but frequent variations, but entirely different lines, as if the voice actors got re-writes while the subtitles were never updated. It’s actually rather disconcerting, so you may either want to look away or just ignore the voices and click through anyway.

Of course, you could just turn the sound down, but that would mean missing out on the game’s quite extensive soundtrack. It’s all fairly unintrusive and changes according to location, though some scores work better than others. The eastern-flavoured FORT music is something I actually looked forward to, while I cringed at the muzak-type tunes of some school environments. The repetitiveness of the more heavily-visited areas did begin grating over time, however – yet another casualty of the game’s over-indulgent storyline.

The artwork of Lux-Pain is classic anime: the girls have short skirts, the men look effeminate (Atsuki himself is described as having "beautiful ash hair and a feminine white face"), and all characters have large, round eyes, fashionably creative hair styles, and exaggerated facial expressions. If you like anime, this is definitely one of the game’s strongest points, and indeed it comes packaged with a separate “Art of Lux-Pain” booklet, which is quite attractive but would have been nicer if it actually fit inside the game case and not been carelessly taped to the outside. In-game animations are few and far between, however, and the static locations, from various school rooms to the civic hall to apartment complexes to businesses in town, are surprisingly blah. Then again, really they’re only present as backdrops to the characters that dominate them.

Unlike most DS games, both the bottom and top screens show variations of the same scene. The bottom screen shows the “real” details, while the top screen shows a ghostly, ethereal version representing Atsuki’s special insight. While an interesting concept, in practice the top screen is all but ignored until it’s time to engage in the only thing that really passes for gameplay in Lux-Pain. After roaming around talking to whoever is waiting for you everywhere you go (a map screen often lets you choose the order of pre-determined places to go, but you'll typically need to visit them all anyway), eventually you’ll encounter someone or something with a Shinen to expose. To do so, you simply rub the stylus frantically across the touch screen to “erase” the surface layer of the image in order to find one or more small chains of blobs moving randomly around the screen.

Once you’ve uncovered a “worm” and a wide swath around it, you simply tap and hold the stylus against it for a few seconds until it turns into a text phrase like "Black urges" or "Filthy world". In turn, these terms lead to a series of stylistically-generated longer expressions meant to denote a predominant thought sequence or emotional state. Letters will float in from all directions at different speeds, forming multiple sentences on screen in various states of completeness. Annoyingly, both the timing and the effects used make it difficult to read these phrases in full, let alone understand them. It’s like trying to read poetry through a kaleidoscope – which sounds way more interesting than it actually is here.

Sometimes there is only one worm and the event is untimed, while other times there are two or three (and as many as six in the endgame stages) with a timer counting down. It’s not overly difficult, but there’s little margin for error, and if you happen to fail, the game simply ends. You lose, game over. No restart, no recent checkpoint, just a forced reload of your latest manual save. Adding insult to injury, you can’t save once you discover a Shinen, so if you’ve been mindlessly lulled into a false sense of security by the half hour of uneventful conversations leading up to that point, hope you like hearing them all over again.

The Silent is the big game you’re really after, however, and among the many dozens of Shinen, you’ll encounter twenty or so of the larger parasites. For these you get… a whole new minigame! Three varieties, even. One is simply touching spots as they appear (yawn), another sees you frantically tapping panes to break through them in time, while the third has you connecting lines to the four corners of the screen. How any of that even remotely resembles fighting a parasite is beyond me, but successfully defeating its obstacles will deplete its life bar, while failure decreases yours.

After each encounter with both Shinen and Silent, you’re assigned experience points that eventually allow you to upgrade to gibberish levels like “FORINCAP” and “VISIBEA”. You never know how near you are to the next level, but when you reach one, you’re given an increase to such things as erase width and time. This RPG-like addition could have added a strategic component if used wisely, but since the huge majority of points are accrued simply by winning the encounters, the upgrades are all but guaranteed and have no overall effect.

Also providing no effect are a few other sporadic “gameplay” elements in Lux-Pain, none of which amount to anything more than filler. You can collect people’s personal profile “cards” and mobile ringtones, but there’s no real incentive to do so, nor any clear instructions for how to go about it. I generally just got one by visiting a random location or speaking to random people at an unseen trigger point. Meanwhile, a particularly flaky shop owner asks you to take her personality quiz every time you visit. I quickly stopped visiting.

All told, it took me an internally-clocked 18 hours to reach the end of Lux-Pain… or about 17 hours and 40 minutes longer than its gameplay actually warranted. Oh, there’s a decent little pseudo-spiritual thriller buried somewhere inside, but like hunting the Shinen, you’ll have to scribble your way through all the many layers of excess to find it. I commend the developers for taking an experimental approach to storytelling, but whatever value the game may have achieved artistically, it fritters away with its abundance of misplaced social teen padding and repetitive, meaningless minigames. If you’re up for something new and altogether different, you’ll find plenty of what you’re looking for in Lux-Pain, but though it hurts me to say it, everyone else will find the game about as much fun as high school detention.